Kardinal Offishall Explains What Toronto Hip-Hop Was Like Before Drake

On the occasion of his fifth solo studio album, a T-Dot legend traces his history, and his city’s.

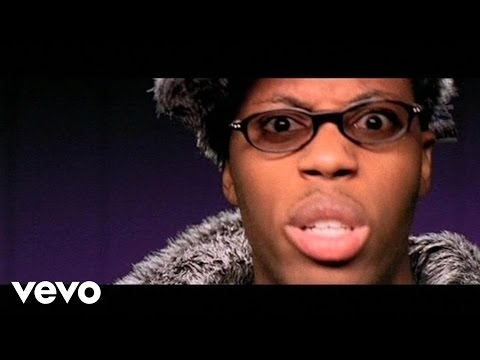

Before Drake's ascension from child actor to pop star and globally recognized 6 God, the king of Toronto's rap scene was Kardinal Offishall. Throughout the '90s and early 2000s, he stood as Canada's greatest proposition for crossover success, a rapper who creatively blended traditionalist rap with the dancehall of his Jamaican heritage and, by doing so, captured a sliver of Toronto's diverse, immigrant-led culture. There were others, too—rappers like Maestro Fresh Wes, Saukrates, and Choclair were heavy hitters. But it was Kardi whose name rang loudest around the world. Still deep into a two-decade-long career, he dropped his fifth studio album, a wide-ranging project called Kardi Gras Vol. 1: The Clash, earlier this fall. On the occasion of its release, we caught up with the T-Dot legend to find out more about what it means to be a rapper from Toronto and what Toronto means to rap.

KARDINAL OFFISHALL: Right before I got my first deal with MCA Records [in the ‘90s], I was with [director] Bobby O'Neill, Little X, a bunch of other cats. We were in LA and standing on top of a roof. I remember them saying, "Yo Kardi, you have to continue to travel the world. You have to get out of Canada. Make sure that everybody knows you everywhere." I have this thing I live by: It's not about who you know, it's about who knows you.

The whole foundation for me was built pre-Internet. We actually had to go out there and meet people face-to-face. I say “we” because I very rarely, in the early days, did anything by myself. We were always cliqued up so it was myself, Saukrates, Choclair—that was pretty much the trinity. Although our squad was huge, we could only afford for the three of us to travel. That's why we know all these legendary people like Sway & King Tech, Stretch and Bobbito, because we used to travel to America and Europe. We would form relationships first-hand. Those were real friendships that we formed with people who know where I come from and saw me go from being a little ghetto kid from Toronto, from the hood—saw me work my way up from various stages to where I am now.

Hip-hop [has] reached a new age where people are transitioning into being the OGs. At first, it was weird but I think I've embraced that OG status for my city. At the same time, hip-hop is growing up and people who were 18-25 are now 25-40, and they still love and embrace hip-hop. It's a very transitional time that we're in within the culture. Of course, everybody has eyes on Toronto right now. But they just have eyes on Toronto, they don't necessarily know what Toronto's history is. They don't know what our legacy is.

For myself, I'm somebody who from the age of 12 has been performing in this city—literally there is no place I haven't performed in the city, much less the country. It's important that I'm able to let people know what our city is about. I don't want our culture to just be swept up in a blanket of pseudo-"Down South" type shit. What used to separate us from the rest of the world, if you look at the legacy of MCs that came from Toronto, people who came way before me, is that they're all people who put their culture to the forefront. Maestro Fresh Wes, Dream Warriors, Ghetto Concept. The thing that made them different was the way that they approached the music.

When you used to think about Toronto MCs before, there was always a cultural aesthetic to it. Even if you look at somebody like K'naan and him embracing his African legacy and his lineage, all those things were super important to who he was. Look at somebody like Nelly Furtado, who embraced her Portuguese side. It's just one of those things that we did here because multi-culturalism is a big part of who the city is. A lot of people come to Toronto like, "Yo, this is crazy! You've got everything here! You have Indian people, Somalis, Ethopians, Filipinos, people from the Middle East, Caribbean people.” That's what our city is. It's an important part of who we are.

Besides the cultural aspect to it, the other thing is that our city has gone through a lot of trials and triumphs. It's not very well documented within the Toronto hip-hop history but government policing played a huge part in what helped shape the city as well. If you look at the L.A. area riots after Rodney King, that had a ripple effect in Toronto. From that ripple effect, the provincial government implemented programming that helped take kids off the street. It was called the JOY program: Jobs for Ontario's Youth. From that JOY program, they partnered up with the Toronto Arts Council and created a program called Fresh Art. From the Fresh Arts program came myself, Saukrates, Choclair, Director X, we all came from that program. It had direct correlation to government implementation of programming that was aimed at helping take kids off the street. It was from that Fresh Arts era that so many things were born.

Saukrates and my crew were the first ones to get a deal in 1995. He signed to Warner Brothers in L.A., which was a huge thing. Choclair went on to get a deal with Priority Records in America. Eventually, I went on to get a deal with MCA Records in America. We visited New York and one of my employees at the time was Little X. We dropped off his director’s reel to Hype Williams and from that he was able to get an internship and work his way up in the ranks. There's so many stories like that that the world is unaware of because they're on a wave, on a hype, because Toronto is hot, but they really don't know how much our city went through and the different people that literally put their lives on the line so that MCs and DJs and directors could have a shot at international stardom.

For us, we've always loved to see our own people do things, not just in America but internationally. I used to find a source of pride when Maestro did a song with [New York rapper] Showbiz. That was a big deal for us way back in the day. The same goes for me when people started seeing me on BET. I think it's super dope to see Drake and The Weeknd do their thing. Bieber's not really from Toronto but close enough. At the same time, it's not necessarily Drake or The Weeknd's responsibility to educate people about the legacy [of Toronto]. Drake just turned 29, so when a lot of this stuff was going on, he wasn't really old enough to know really what's up. Not in a bad way, but he was a TV star! He had TV shit to do. His ascension into where he is now is very different from your average MC anyway, your average kid from the hood.

I think we would be wrong to place the responsibility on [Drake or The Weeknd’s] shoulders. I think what they're doing for the city is amazing. They're still relatively young, and you can see the Toronto pride and being Canadian-centric, that's starting to be more and more a part of who they are as artists. At the end of the day, that's what it's all about. That's what myself and the people that came before me, I think that's what we always wanted. Now that we see it, it's amazing, but just because Drake is the biggest thing on the planet doesn't mean that he's also supposed to be responsible for being the promoter of all things Canadian.

I think with myself, with him, and others, we have now come to a point where we can be very resourceful. Here in Canada, we have to do ten times the amount of stuff to get proper recognition. In America, just citing certain artists, you can look and be like, "Shit, this person came out with one album, and they're immediately embraced." In Canada, you might have to come out with four albums. If you look at a lot of the trials and tribulations that Drake went through, even at home, it was not always this easy. I remember the earlier days when we used to have more interactions. It wasn't easy for him in the beginning! I remember when he wanted to work with Nottz. I remember having to call up Nottz and tell him about this kid. Eventually, people met him like, "Yo Kardi, he is dope." But it wasn't it like he just got the golden key to the world and was always loved and embraced. He had his own trials.

But we [in Toronto] are definitely in a good position. That's where the OG part comes in for me, is to really just use my voice and let people know what it is. I think that's always been a part of who I was. Literally from the very first song I had on the mainstream, which was "Bakardi Slang," it was a song about the city that I came from, the slang that we used and the styles that we did. That was always my mandate from day one.