On The Occasion Of Black Genius

Like the prodigious artists before them, Kendrick Lamar and Kanye West create work that allows us to know ourselves and order our world.

Artists have the ability to set alight our most treasured joys. Be it through a song or a book, via a poem, painting, or a photograph, this offering can bring to mind the things we have proudly carried with us our entire lives. And it's here, in the process of accepting this offering, where a procession of warm memories greets you: teenage nostalgia wrapped in a ribbon of summer sky, that one fall day when a new crush messaged a series of smiling emoji, the cushion of your sister’s voice over the phone as she tells you about her week. Our most important artists summon these sentiments through their work. A song like “Real Friends,” for example, transports me to 2004 and then to 2012, periods of my life when core friendships were built and tested. The song prompts me to consider the personal bounty I’ve been blessed with, one I could never quantify in capital.

In addition to this, there are certain artists who possess, beyond the boundaries of our admiration for their creative mastery, an uncanny power to awaken our deepest and most sacred sentiments. Author and essayist Ralph Ellison wrote a version of that line in 1958 regarding Mahalia Jackson, the black gospel singer whose mighty contralto was once described by Martin Luther King Jr. as a “voice [that] comes not once in a century, but once in a millennium.” I use it here because Ellison’s observation of Jackson captures the essence of what artistry can accomplish when wielded properly: the ability to light something within us, to reach those of us in desperate need of some semblance of salvation.

Sometimes this lighting kindles feelings we cannot easily name. It is not so much that we have forgotten how to name them, but rather it is the proximity with which these feelings live in relation to experiences or memories we have entombed somewhere dark within ourselves. And for this reason we have vowed to never return, to never name them again. Part of this decision is survival. Choosing to not name past impressions becomes a conscious act of self-preservation that manifests outward: ignoring a phone call from an ex, foregoing a night out with friends again for the solitude of your apartment, deciding to return home after years away to people and places that no longer welcome you with the kind of love you once knew. These are moments that can trigger feelings of regret, loneliness, apprehension.

But it is the genius artist who, over a sustained period of time, is able to continually produce work that gives name to sentiments hidden, shared, and long forgotten. It's in this space—in the hard, messy work of genius—where the artist, as Ellison witnessed, is able to reduce “the violence and chaos of American life to artistic order.” Black artistic genius—that is, singular brilliance that was nurtured in and speaks to the pulse of black life—is a statement or body of work that exists so absolutely (in verse, on a canvas, on the page, etc.) it bestows a transformative power: to light, to name, and to order all that is within us and around us.

This ordering, however, does not happen without sacrifice. Sometimes this sacrifice is the body. Sometimes this sacrifice is pride. Sometimes it is a complete sacrifice of the mind. James Baldwin, the Harlem expatriate author who knew something of sacrifice and a great deal about genius, is helpful here. Writing in 1963, he described what sacrifice meant and why it was necessary for the artist to give oneself fully to their work.

“[M]illions of people whom you will never see, who don’t know you, never will know you, people who may try to kill you in the morning, live in a darkness which—if you have that funny terrible thing which every artist can recognize and no artist can define—you are responsible to those people to lighten, and it does not matter what happens to you. You are being used in a way a crab is useful, the way sand certainly has some function. It is impersonal. This force which you didn’t ask for, and this destiny which you must accept, is also your responsibility. And if you survive it, if you don’t cheat, if you don’t lie, it is not only, you know, your glory, your achievement, it is almost our only hope—because only an artist can tell, and only artists have told since we have heard of man, what it is like for anyone who gets to this planet to survive it. What it is like to die, or to have somebody die; what it is like to be glad… The trouble is that although the artist can do it, the price that he has to pay himself and that you, the audience, must also pay, is a willingness to give up everything, to realize that… none of it belongs to you. You can only have it by letting go.”

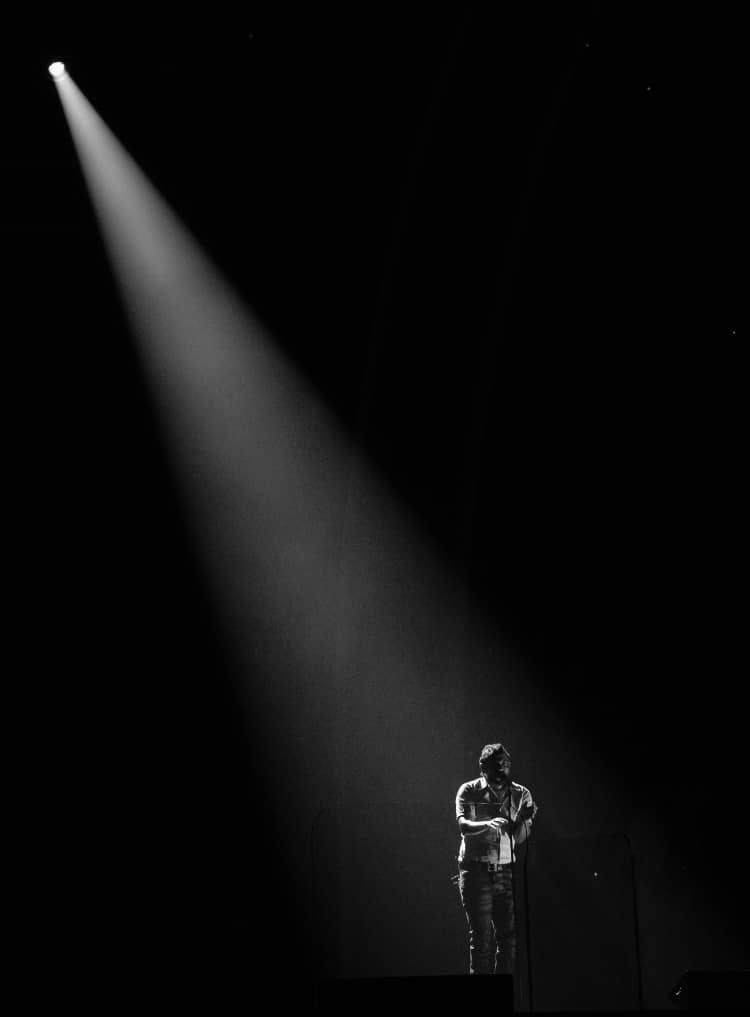

Here then is Duke Ellington and John Coltrane joining together in 1964 at Van Gelder Studio to record “In a Sentimental Mood,” a song Ellington had composed 30 years prior but one which would not find its true potency until the pair’s providential 1963 album. Here is Nina Simone, a woman who offered us her blackness in full unsparing breaths, singing Hound dogs on my trail/ School children sitting in jail/ Black cat cross my path/ I think every day’s gonna be my last to an all-white audience in Holland in 1965. Here is Richard Pryor in 1974 on Burt Sugarman’s The Midnight Special, talking about the unmoving fortitude of black folk—“Because after 400 years of this we don’t get scared of nothing, for real”—and the crowd knowing exactly what Pryor meant by this: the weight, the blood, and the horror of history. Here is Chloe Ardeilia Wofford, before she would present us with the world-affirming majesty of Toni Morrison, sitting to write about Pecola Breedlove and the fall of 1941, the year there were no marigolds. Here is Dave Chappelle crafting a sketch about Brenda Johnson “keeping it real” just months before we would persecute him for keeping it real after abandoning Chappelle’s Show. Here is Miles at his best and his most misunderstood. Here is Aretha and her thundering voice. Here is Stevie. Here is Prince. Here is Quincy. And Gordon Parks with his camera roaming 125th Street to capture more of the black beauty the world had been working so hard to disfigure. Here is Dilla on Fantastic Vol. 2 and again on Donuts. Here is Kara Walker and her grand Antebellum-era silhouettes that evoke the poison and promise of early America.

Freedom for the black artist has often been misunderstood for everything except what it actually is: a truth that can be hard for outsiders to swallow.

And because black genius is a constant echo from the fore to the present, it must always find new ways to reveal itself to the world. Out of this genealogy arrive Kanye West and Kendrick Lamar, two artists who have added considerable depth to our understanding of blackness by offering up complex and complicated renderings with each forward-pushing album drop. They have named our joy and hurt, our mania, sadness and struggle with a sort of precision that can be easy to mistake for vague or fragmented ideology. On The Life of Pablo, a sumptuous oblation from West released in February, the artist presents his genius in the temper of Duke Ellington and Quincy Jones: that of grand orchestrator. Perhaps this is what Baldwin meant when he wrote about the artist letting go as a means of arrival; West gives himself so fully to the work that the most intoxicating songs from Pablo are the ones that find him absent center stage (“Ultralight Beam” is all Kelly Price, The-Dream, and Chance; “Father Stretch My Hands Pt. 1” falters without Kid Cudi’s soaring croon; “Waves” belongs wholly to Chris Brown). Even more than Pablo’s technical profundity, the album expands our understanding of just how black genius has manifest in modern America

Consider our current moment—for black Americans, the current moment has more or less been the same moment throughout history—and how an artist like West has set out to order “the violence and chaos” of life around him as spectators have worked to confine his musical talent, which has become even more transcendent with each successive release. He has attempted to amplify his voice as the world has plotted to shrink the creative force that moves through him—or, what Baldwin would refer to as “that funny terrible thing which every artist can recognize and no artist can define.” At times this negotiation, between the black artist and the world, a world which is also attempting its own kind of ordering in opposition to the artist, can take the shape of emotional instability, aloofness, or detachment.

It often looks as if West has buckled under the pressures of public furor. His recent presence on Twitter, for example, has come under much scrutiny for its undisguised forthrightness. Has he lost his mind, many have wondered. But freedom for the black artist has often been misunderstood for everything except what it actually is: a truth that can be hard for outsiders to swallow. And in this denial of truth, in this denial of black artistic genius, it is often labeled something other and far worse: madness. Nina knew it. Chapelle did too. And yet, we are made better and more whole because of an artist’s diligence and sacrifice in spite of all this. It is this genius West recognized, and defiantly labeled as such, on a guest verse for Tyler, the Creator’s “Smuckers”: I am the free nigga archetype.

West obviously wasn’t the first, though he does grant the paradigm new life. It’s what black genius has always been, and will always represent at its peak: untethered creative freedom in spite of a world laboring to diminish the black artist to a nigger.

Perhaps this is why Kendrick Lamar, the prodigious Compton emcee, is slowly becoming one of our most abiding musicians: he creates freely and fully. He seems to embrace his artistry with a lucid hyper-awareness of his own blackness, which lends clarity to a pop landscape where imitation and mediocrity are often rewarded over originality. Lamar’s is a genius which is just now coming into view, one we are fortunate enough to watch bloom in public, and one that was made even more transparent with the release of untitled unmastered, the eight-song EP issued late last week. Although the EP is a loose collection of unfinished throwaway tracks—according to TDE co-president Terrence “Punch” Henderson, they didn’t fit the musical arc of To Pimp a Butterfly—it has, in the days since its surprise drop, added more depth and context to our understanding of blackness by complicating our idea of it.

In that sense, untitled unmastered serves as an extension to Butterfly’s charged politics, rather than a new proposition. Promise momma not to feel no lie/ Seen black turn ‘em Burgundy/ Hundred of them, I know I’m greedy/ Stuck inside the belly of the beast/ Can you please pray for me, he raps woozily over “untitled 02 | 06.23.14,” charting his course and confliction from Compton to the top of the charts. This internal quarrel has followed Lamar throughout much of his recent work. Later, on “untitled 08 | 2014-2016,” he offers a slick morality tale on the economics of black life: I hit the bank today and told them color me bad/ Blue faces/ Get that new money, and it’s breaking me down honey.

In the three years between good kid, m.A.A.d. city and Butterfly, Lamar’s artistic vision ballooned exponentially. untitled unmastered opens a window into that process; much like his previous album, the EP illuminates long-buried sentiments. It is an ordering out of disorder. A salvation. An acknowledgement. A love letter written to kinfolk never sent until now. Lamar, like Nina and Miles and Stevie before him, names our pain, our gratification, and our anger, so that we may feel moved enough to give voice to it, too.