The Very Black Politics of Prince

Prince was more than his music—he was a look, a feeling, and a politics rooted in blackness.

“Take any of the blackest berries… and on close inspection with the eye, the hue will be really a deep or dark purple.” —Martin Robison Delany

Just 24 hours after news of Prince's death, public memory has already started to break for bad. And do the thing. You know the thing. The thing that involves a lot of sweeping, namely the distasteful a.k.a. radical a.k.a. black/queer bits of a person under the rug to better befit the narrative of how some prefer to remember their icons. The thing that memorializes Him, the already long-immortalized integer to post-’70s sound, to a whitewashed cast known nostalgia. Many, including (yup) M.I.A., have already paid what they think are respects in a way that rewrites Prince as the late sovereign to a post-racial wonderland. And that simply will not do.

Prince was black as fuck. His politics were black as fuck.

We can begin with recent memory, with “Marz,” “Baltimore,” and the May 10th Rally 4 Peace benefit following the murder of Freddie Gray by Baltimore police—all three echoing the overt anti-armament language of early work like “Ronnie, Talk to Russia,” nuanced and evolved to the present. We can make a listicle, compile Prince’s most blatantly political songs of all time. (Remember when he went in on Wall Street?) We can debate whether these songs fit the protest genre or altogether pose something new and different. We can configure a genealogy, situate Prince within a heritage of black communism, socialism, or what I like to call the-diverse-coalition-of-black-folks-protecting-their-labor. We can talk about his politics that puts its money where its mouth is, real money that changes things on a macro and local scale. We can compile interviews, soundbites, lyric excerpts, and see what they add up to. We can make a bibliography of sound and only sound. We can analyze sentiments in and out of lyrics, discuss tensions between internal contradictions. Much of this has been done. Some of this is in the doing and re-doing. All of this is important.

But I prefer to start with a look.

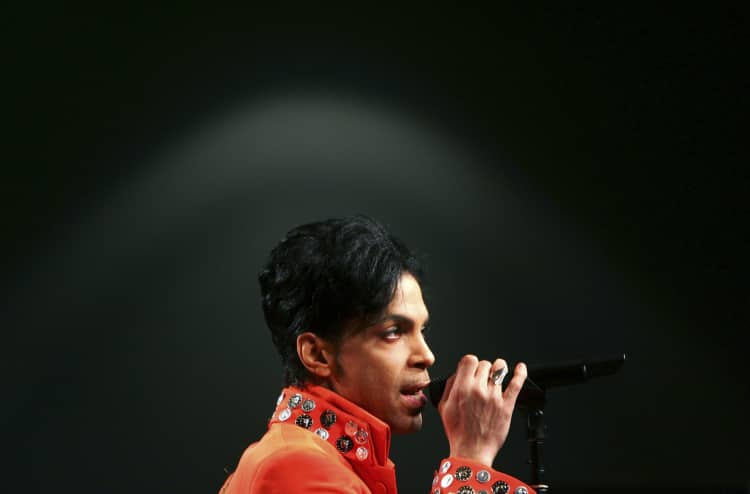

February 9, 2015: Prince strolled onstage to present the Grammy for Album of the Year. His look, as always, was a feeling. A simultaneously blessed touch on the forehead and lick on your inner thigh. A brilliant breath of ‘fro and funk from times past. (Only, it’s Prince, so times past are also His times present. Times eternal.) The audience full of artists and “artists” stand and applaud, knowing better than to do anything else. Audiences at home do so too, forgetting if only momentarily the maybe-axe that eventually did fall on the most innovative album nominated. Then there is the Look. The undeniable side-eye into infinity. (If you don’t know what that is or what it signifies then that sucks and I’m sorry, but I can’t help you. If you think you know what that is because you read about it in The Atlantic or something then I’m not sorry at all and also please refer to the previous statement.) In a retrospect that began just 20 seconds after the look was given; Look was scooped into a commentary on rigged results.

But the Look came before. It was pre-reveal. Or maybe still post-reveal—after all, Prince is not and has never been bound to the same temporal order as the rest of us. In any case, it doesn’t matter. There’s another knowing there. Though conspicuously edited out of the official online Grammys award recap, the Look prefaces the carefully delivered statement that followed: “Albums… [another look]... still matter. [another another another] Like books and black lives, [more more more] albums still matter. Tonight. [look+grin] Always.”

As he stood on that stage in front of those people, it’s a moment so ripe as to be gushing in its signification. It’s a moment that looks and Looks back to itself, to Himself, to a series of acts now reduced to the non-utterance of a symbol that is actually symbolic of a radical transformation of the possibilities of recognition and compensation for black artistry and labor. (Yes, that momentous period when Warner Bros. exploitation pushed him to seek another name, but also a career-long advocacy for the mainstream relevance of black sound.) Ongoing side-eye into infinity. A soul-deep politics spilled at the level of the face. It’s the barest glimpse of politics as a living, rippling, signifyin(g) project not incompatible with affect, art, magic, form, structure. It is so damn black it hurts.

That audience couldn’t possibly have grasped it. As I see it float down my timeline in still captures or gif form, I wonder which folks really do.

Politics matter. Prince’s politics matter. It matters that this politics was and is, in all ways, invested in black lives and black futures. It matters that this politics were constantly aired in those kind of rooms. Amongst those kinds of people. Even if sometimes only at the level of the face. It matters that we are right now witness to a kind of revision, that we can observe in real-time the blackness of his work swept away due to discomfort. This is not anybody’s Prince political primer. Only an ode to otherbeingness that spoke the tongue of the standard but never departed or forgot the black vernacular of being. Lest we forget, I think I’ll say it again:

Prince was black as fuck.