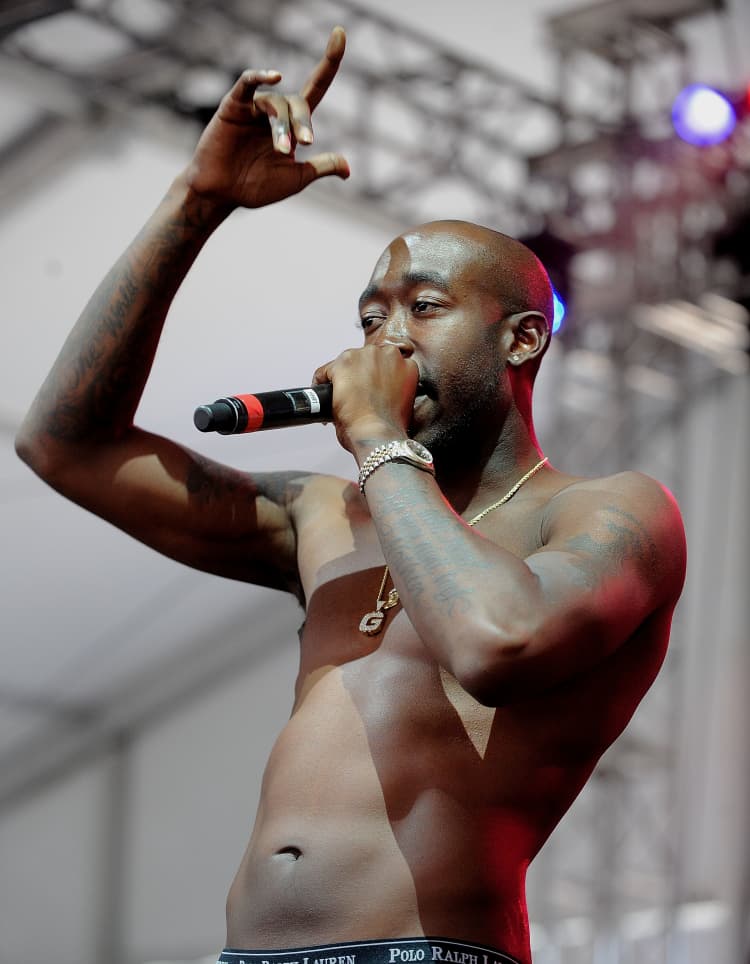

On Bandana, Freddie Gibbs plays to his strengths

In his newest collaborative project with Madlib, Freddie Gibbs masterfully sticks to what’s worked for the bulk of his career.

A half-decade ago Freddie Gibbs and Madlib finished, mastered, and packaged Pinata, an album whose songs had been trickling out on EPs for more than three years by that point. The beats, they said, were pulled by Gibbs and his management team from the ether. When I say “packaged” I mean the cover was a mat of zebra fur inlaid with a photo of Gibbs, perched on a park bench, smoking in an Adidas sweatsuit; when I say “ether” I really mean countless CDRs and tomic hard drives. It was dense, strange, luxurious, punishingly mean. Madlib would parachute in occasionally to make finishing tweaks and finishing touches, but Gibbs was left mostly alone with his grim, mercenary raps, grafting them onto beats that in some cases seemed absolutely complete without vocals. Madlib’s reaction when he heard the tracks Gibbs had chosen was one of mild surprise.

Pinata is a great rap record in spite of how loudly and conspicuously it tries to be a Great Rap Record. While Gibbs has never been prone to trite or writerly flourishes, his sensibilities are from a past era where albums have long, wrenching emotional arcs, and the stakes written into, say, the Scarface collab are unmistakably high. The album is at turns steely and warm, venomous and silky, swaggering and even whimsical. In some senses, Gibbs was simply executing the same songs he’d been executing since he was dropped from Interscope in the middle of the 2000s. But he was digging deeper and, just as importantly, doing so with the resources and in the context that would invite closer critical attention than he’d received in years.

Gibbs has released a slew of solo music since Pinata, but Bandana represents the most anticipated record of his nearly 15-year career so far. It was made under, well, trying circumstances. Some time in the first half of 2016, Madlib sent Gibbs another pack of beats. (He made these ones on his iPad, an interesting admission from the kind of reclusive artist who tells interviewers that he doesn’t own a cell phone.) But in June of that year, Gibbs was arrested in France and extradited to a jail in Austria, where he faced charges of sexually assaulting a woman in Vienna the year prior. He spent four months in jail, writing to whatever skeletons of the Madlib beat pack he could remember. At the end of September, he was acquitted and returned to the States.

The songs that were written during that period, and those that were added in the two and a half years since Gibbs returned are, predictably, studded with painful memories. But Bandana is notable for being looser than Pinata and at many points seems to invite lower stakes; the first song is titled, simply, “Freestyle Shit.” Compared to its predecessor, Bandana’s beats sound as if they were made expressly for Gibbs, which is both a blessing and curse: there is now an undeniable chemistry, but part of the thrill of Pinata was hearing the Gary, Indiana native over small, psychedelic Madlib vignettes that seemed worlds away from, say, ESGN.

Its best moments are its strangest: the staggering, tortured last verse of “Situations,” which is delivered in a double-time that it doesn’t seem to need, but which comes to elevate it; the laconic second half of “Flat Tummy Tea” and the complaints about the ubiquity of slave movies; the gasping “Palmolive,” where Gibbs rails against vaccines; the relentless, shifting “Fake Names”; even the patient midtempo of the Yasiin Bey cameo on “Education.” Gibbs is not interested in reinventing the wheel in any macro sense, but many of the little component parts of the record are made to feel new and fresh and alive. Bandana doesn’t quite reach into your chest cavity the way Pinata does, but it’s set up so that it doesn’t need to in order to succeed.

Last year I was in Berlin at one of those music conferences conjured by an energy drink company. The thing culminated in a long interview with Pusha-T; they sat him on a couch in front of a backlit screen on which his lyrics had been scrawled in cursive, like those Declaration of Independence step-and-repeats that presidential candidates shake hands in front of at steak frys. At one point he sort of smirked at the interviewer and said that, “I mean, if you want to talk about it, I really made variations of the same album for the past 20 years.” I thought of that during his verse on “Palmolive,” where he snarls “We all break bread like going Dutch on a dinner date,” hitting the double-d dinner date with the exact same venom as when he rapped, in 2013, “Arm & Hammer and a Mason jar, that’s my dinner date.” Pusha is a specialist. He’s rapped so doggedly and with such tunnel vision in a single direction for so many years that the song in his catalog that would stand as the starkest outlier explicitly references what a stark outlier it is.

On paper, Gibbs has more emotional range in his writing than Pusha ever did: he slips into tangents about his own jealousies in a way that would seem to undercut his rhymes on other songs, and he writes about the trauma and psychological baggage he’s accumulated in a way that does more than underscore the danger he faced and overcame. But where the rappers are similar is that the subject matter is not meaningfully different than it was a decade ago, when Gibbs dropped The Miseducation of Freddie Gibbs and midwestgangstaboxframecadillacmuzik in the same summer. On a given record he’ll rap with chilling remove and then deep feeling about similar incidents; he’ll bounce from threat to embarrassed aside. And then he’ll do this again two, five, ten years later. For some artists this would yield a catalog that seemed repetitive and directionless. Gibbs is a practiced enough writer –– with a compelling enough voice, and with the requisite wit and capacity for surprise –– to instead make this flat-circle loop seem rewarding.