Heroin, hustling and a kinship with witch trials aside, the members of gutter industrial trio Salem are more delicate than damaged. Like many salient artists, Heather Marlatt, Jack Donoghue and John Holland have wounds to spare (Holland’s salacious sex-for-drugs backstory was recently featured in Butt magazine). Unlike many, Salem isn’t jaded. “We’re, like, children,” Marlatt says. And like children, they’ve retained their innocence by living and creating with abandon.

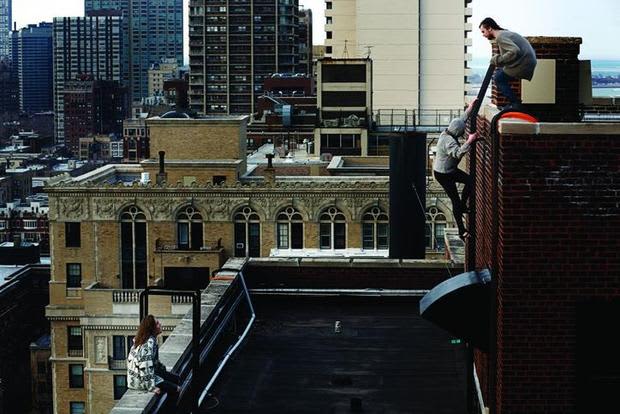

Because Salem’s still gestating, they’re loathe to subscribe to any defining philosophy, even a suspected nihilism. They technically hail from the Midwest (Chicago via Michigan), but in their two years together, have constructed an alternate, corroded purgatory where nebulous genres collide. Conceptually, they’re almost classical, though screw, juke, and disembodied bass all feed their murky lo-fi sound. Marlatt’s wispy vocals, coated in a Gregorian patina, serve as a foil to unholy synths on tracks like “Redlights.” On a frosty rendition of Springsteen’s “Streets of Philadelphia”, her voice is a siren call to drown happily, in stark opposition to Donoghue’s demonic rap on “Trapdoor” or Holland’s distorted murmurs on “Water”, which doesn’t flow so much as vaporize into cloudy stutter. Listening to their body of work is an exercise in interpretation: Hip-hop is a dirty constant, electro is cinematically atmospheric.

“It’s a progression, but not necessarily one that builds,” says Donoghue, describing Salem’s nonlinear anthems. Like their makers, the tracks are shapeshifters and celebrate release, whether from comfort or nightmarish inevitability. “When I want to make music and John doesn’t, it’s like blue balls,“ Donoghue confides. “I want to get off and I can’t.”

Despite their willingness to discuss just about everything else, Marlatt and Donoghue aren’t as forthcoming as Holland with their personal histories, though they hint they’ve been through a lot. They pontificate on how their pasts shaped them—if they hadn’t faced adversity, what type of music would they create?—before devolving into a retelling of favorite bedtime stories. Clearly, those looking for an articulated purpose won’t find one. Yet lack of mission didn’t stop them from producing two stellar EPs, the first of which, Yes I Smoke Crack on Acéphale, sold out before it finished pressing, and Salem’s sinister full-length is set to drop on Merok Records at year’s end.

For all their surface vagaries and dips into puerility, there’s a breakthrough when we talk about the dreaded comparisons that liken Salem to other, more danceable acts. “When people compare us to electronic music that doesn’t make anyone awake or uncomfortable, I don’t like it,” Donoghue is quick to correct. “We’re not video games.” So, there’s emotional intent behind the black curtain? “Well,” Holland says, “If you’re listening for the first time, I want you to lie down on the floor and really listen. The music that we make is the most important thing in my life, it’s the only thing I’ve ever cared about.” In that, Salem not only escaped the pollution of childhood suffering—they’re imparting the secret to whoever’s awake enough to listen. You’ll never outrun the darkness, so just let it pass.

Stream: Salem, King Night