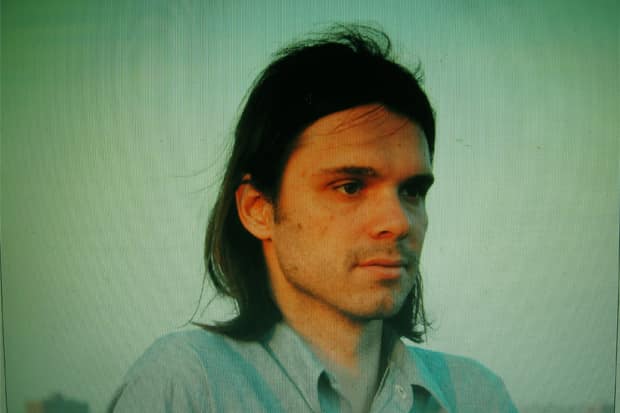

A sunglasses-clad David Longstreth sat down with us in a suite at the Wythe Hotel in Williamsburg, Brooklyn (his "56th interview of the day") to talk about Dirty Projectors new album, Swing Lo Magellan.

Swing Lo Magellan is billed as an album about songwriting. How is this particularly different from other albums you’ve written? Earlier Dirty Projectors albums are organized around a single idea, you know, whether it’s remaking Damaged the Black Flag album from memory or telling a story you know about a teenage Don Henley wandering through a futuristic dreamscape, post-apocalyptic America or something, as was the case on The Getty Address. Or Amber [Coffman] singing to a pod of whales, which is what Mount Wittenberg Orca is about. Or even just to present the live band as kind of like brand onto itself, which is sort of what Bitte Orca was about—to create an emblem of this live unit that we had become and sort of burnish it into this thing resembling a brand. [Swing Lo Magellan] does none of those things. I just got obsessed with songs, you know? I’ve spent the better part of the last ten years being obsessed with music—pursuing what was foreign to me, what felt new, what felt strange, what felt abstract and to a certain extent, I was like one of those people in the culture, whether you realize it or not, whose job is to assign meaning to things that didn’t have meaning until you went around and fucks with ’em.

What do you mean? You know just taking something that doesn’t mean anything and tagging it. And then if somebody else takes the tag and makes more money off of doing it somewhere else—but I mean, whatever. This isn’t about that because I feel like those are all very old ideas and the even older idea, and the one that I just kept on—it’s in my nature to just question everything all the time—the thing that would just pose more questions back to me that I couldn’t answer, was just "the song." The song itself. This undeniable little unit. And it just seemed like, for me with the kind of music that I’ve written and the music that we’ve made as Dirty Projectors, that seemed like the most daring thing that I could really do on a personal level and on a creative level, is try to do that: just take the simplest tools and obey the rules to a certain extent.

Do you feel like having had strict concepts for the albums leading up to Swing Lo Magellan has allowed you to open up to the idea of making an album for the simple joy of songwriting? Yeah, I mean there’s no way that I could have done this at any point earlier. There’s no way. For me it’s the boldest thing that I’ve done as a musician.

Do you feel that it also reflects an evolution of the band as a unit? More or less, I mean, for better or worse the band doesn’t really lend itself to registering as a brand. It’s a little bit too out of control to do that. It’s not really been my supreme interest. Every Dirty Projectors album has had a new line-up in one way or the other, but I do feel like I’m kind of going through the world finding the people that are in this constellation. It’s an unfolding thing.

Has Dirty Projectors reached a sort of comfortable stasis, or do you not think that it ever will? I don’t know. It’s not a question that anyone has an answer to. I know it works right now.

You wrote a lot of songs preparing for this album. A lot of them…70 or 80.

What was the vetting process for deciding what would go on the album? Oh, I wouldn’t describe it as a vetting process.

How could you not with 70 songs that you have to then had to whittle down to 12? Yeah, well, certain songs began to run in packs together and others were off kind of by themselves in the corner. The songs on the album really just started to feel like there were these through lines between them musically and lyrically. The period of time that I was writing these songs, I wasn’t thinking about things in terms of an album, you know? It’s an album of songs, but I was just writing one after another—I wasn’t really writing to this concept or something.

Isn’t that sort of a concept in and of itself? To be like, I’m going to write songs. Did you know that at some point it was going to be collected in an album. No, I didn’t know how we would do it. I wasn’t sure whether it would be five albums or something or just all individual songs. You know, when I listen to John Wesley Harding or I’ll listen to Revolver or something like that—I’ll listen to albums from the era of albums, I’ll listen to Rumors, but you know, with [new] music that comes out, I never listen to albums. I don’t listen to anybody’s album really.

Is that something that you regret? Do you look at the "era of the album" as something that’s been lost? Do you?

I’m always very happy when I hear something that feels like it’s a whole and that it’s been considered and has a kind of arc. I mean, I’m a writer so I love a narrative. That’s not to say that I don’t like downloading a song and playing it to death. Yeah. Do you feel like it’s symptomatic of like a certain kind of erosion or something that you can’t listen to a lot of albums?

I think probably there are certain learned behaviors and there’s also the format you’re listening to it in. But you don’t want to get negative about it?

Yeah, I mean obviously. I work for a music magazine. I write about songs. There would have to be something deeply pathological about me if I really hated this, but I was doing it all the time. I think it’s most important that you can adapt. Right.

By emphasizing the idea of ‘songwriting’ and the idea of a cohesive album of songs—one that you would play from start to finish—you know you must have found a narrative, or like you were saying, a thread between the songs that you wrote. Yeah. No absolutely. I guess I shouldn’t be reluctant to talk about those things. It is an LP. It turned into a beautiful LP. Six songs on both sides. 42 minutes. You know, it’s like fucking Zep IV—although that’s not twelve songs, but whatever. Again, for me it felt like the most outrageous or daring thing that I could do as a songwriter—to actually write songs, you know? You know, just writing music in just the most traditional way you could possibly imagine writing. Sitting down and looking at a page or like sitting at the edge of a bed with your guitar you know. It sounds absurd! At the same time, I looked around, and you have music from across the cultural spectrum, from like Coldplay and Rihanna down to, you know, the Woodsist stuff, and it’s like a collection of vapors. It’s all diaphanous, like veils and layers of silt and clouds, and it appealed to me to make something that felt like a very smooth stone just in your hand. Whether that is polemic, I don’t know. Whether it doesn’t do itself any favors transmitting through the medium now. I don’t know.

What were some of the threads that you found when you were assembling the songs for the album? Well, to me the lyrics were very important.

Do you usually think a lot about lyrics? No, I never really cared about the lyrics before. Not very much. I have been so concerned with just sound and textures and tapestries. But [on this album I was interested in] this idea of the grammar of the melody being consonant with the grammar of the language, and the two being in tandem—just finding simple things where the words do what the melody does on a emotional level. The words go somewhere, the words are about something real. That was one of the things that I kept coming back to. And another is just an immediacy and emotional clarity.

On past albums you’ve written specifically for certain members of the band, was it the same for these songs? Like Amber Coffman’s song, “The Socialites” is written from a woman’s perspective. Did you write it for her specifically? Well it’s [written] from a woman’s perspective because it’s sung by a woman. But no actually, I originally wrote that song that way. I don’t think we even changed any of the gender assignations. We might have changed one of them? It ended up being a kind of weird Mean Girls-type of narrative with her singing it. What I originally had was more of like an unrequited high school love life song. Like I said earlier, Bitte came on the heels of touring really hard pretty much straight for like two years. The goal of that album was to create this emblem, this picture of the idea of us as that band. Almost a kind of a caricature of it. To write songs for Amber and to write a song for Angel [Deradoorian] and create things that were sort of more them then they could ever be, you know? In doing so, you can see like this crucial element of what pop music is, which is persona. I essentially created characters almost for Amber and Angel, but it’s weird to have done that. It’s complex to have done that, because foremost we’re not actors. We’re musicians. It’s an interesting thing to have kind of happened into, creating a persona of yourself or your bandmate. Then, you see that’s very, very powerful.

And Swing Lo Magellan is a departure from that mindset? This record is different. It’s a different set of ideas. I don’t know if it creates different persona for me, but what I love most about Neil Young is his misreading of Bob Dylan, which seems to just be like: Bob is just himself. He writes these songs from his heart, and so what I have to do as a writer is just write songs from my heart. And Neil Young doesn’t really seem like there’s a persona there, which is miraculous, if you think about it, it's somewhat unique among the highest echelon of the closed canon that is classic rock. I mean these are just “songs.” These are “songs.” They’re not cartoons.

So you feel like this is more of a Neil Young album? Well, but then it sounds like I’m just addressing that on an aesthetic level, which I’m not.

Not in sound, but maybe just more that these songs are coming from your heart. That’s why I’m wearing sunglasses!

Well, how do you feel when you listen to Bob Dylan versus how you feel when you listen to Neil Young? I mean, I would love to be able to answer that question, but it’s so broad. I love those guys. I love them and, like, Lil Wayne, you know? I don’t know. Wait, you’re probably asking that specifically…I always want to turn around and do the opposite of the thing that I did before.

Why? I don’t know. It keeps it fresh that way. It’s like a crop rotation.

Like you're planting some soy, letting the field go fallow? Yeah, this year we’ll just let it go to seed, and then we’ll come back, and it’ll be more fertile next year.

When you look back do you find these different kinds of approaches, do you look more fondly on certain fields? Well, I think it has mainly more to do with just personal stuff, you know, whether it was fun on that tour, or whatever. I’m a searcher, you know? And so is everyone in the band. We’re exploring. At this point, with the band on the other side of Bitte, when it really is a thing that exists in the culture, it would almost be easier if there was an element of remove between us and this product we created for the culture. For better or worse, it’s not shaping up to be that. It’s still very real and personal. It sort of feels dangerous.