The legendary Stephen Burrows loves to see his clothes out on the floor.

Some designers specialize in gowns to get married in; others, in ones that are suitable for the office; and others still, on little black dresses to wear on first dates. Stephen Burrows has always cared, firstly, about making clothes to dance in—not day wear, not even evening wear, but more like 3AM staples. Burrows honed his tastes while partying during the Studio 54 era, making unfussy clothes in the brilliant shades of red, green and blue that shone brightly in the darkest club. His designs were a huge hit with the disco crowd (Diana Ross and Grace Jones loved his glistening gold minidresses), and he and his posse, including model-muse Pat Cleveland, were invited in 1973 to France by the curators of The Battle of Versailles fashion show for a landmark face-off between American and French designers. Burrows charmed everyone—even Yves Saint Laurent—with a high-energy show, a catwalk soundtrack of contemporary soul and R&B and a cast of black models (rare in the industry at that time) dancing down the runway. This spring, he’s being honored with a retrospective at the Museum of the City of New York and a new book of essays about his work from Skira Rizzoli. Burrows spoke with us about the things he remembers most and why the people wearing the clothes, and the dances they do in them, will always outshine any dress.

What makes a dress good to dance in? That you are free to move as you like—that’s the most important thing. That was my whole idea when I started designing, because before, everything had linings. I liked knits and I didn’t understand why knits had to be lined since sweaters weren’t lined, so I removed all the linings and just had jersey without lining. And you could move. That’s why I like matte jersey: it’s not static, so it doesn’t stick to you. And it was a knit, which I love, because it moves. It’s not restricted.

Were you dancing all the time? Yes.

When did you start going to nightclubs? In high school, in the ’60s, to a Latin club here in New York called the Palladium. It was on 52nd and Broadway. I don’t know how we got in though, now that I think about it—we were only 15 years old! But we went there every Sunday. We loved to mambo.

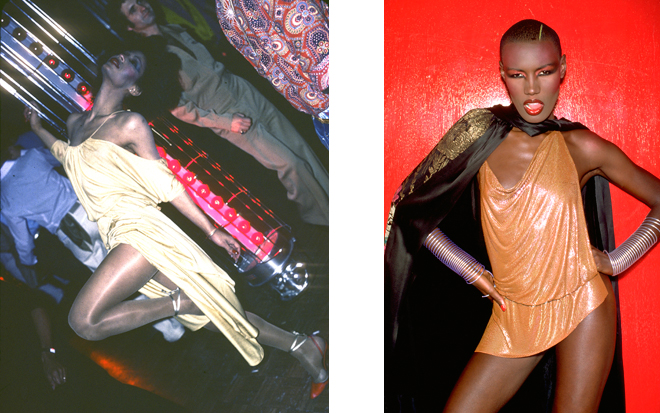

[caption id="attachment_252183" align="alignleft" width="660" caption="LEFT: Acclaimed drag queen Potassa, in off-the-shoulder dress with zigzag finishing by Burrows, at Studio 54, 1977. RIGHT: Grace Jones in gold-tone chain-mail top, 1977."] [/caption]What were people wearing? Oh dear. Then? A lot of peg skirts, whlittle jackets. Mostly peg dresses, which made them dance in a certain way: the girls had to keep their legs together. I started designing dresses for my dance partners. I would sketch dresses for them. I wasn’t really a designer; I had wanted to be an art teacher, but I liked to sketch. And then, in my second year of college, when you have to pick your major, I decided I might try my hand at fashion.

[/caption]What were people wearing? Oh dear. Then? A lot of peg skirts, whlittle jackets. Mostly peg dresses, which made them dance in a certain way: the girls had to keep their legs together. I started designing dresses for my dance partners. I would sketch dresses for them. I wasn’t really a designer; I had wanted to be an art teacher, but I liked to sketch. And then, in my second year of college, when you have to pick your major, I decided I might try my hand at fashion.

How did you get started with your own business? I was busy making clothes for myself, because I couldn’t find things in the store that I liked. So that’s what I spent my time doing, and my friends would come over and I’d just sell them my clothes because they wanted them.

So you just made clothes for your friends to go out in? Oh yeah—Sanctuary, Studio 54, The Loft, The Garage, all the great dance places. It was just exciting. They were all dressed in my clothes. Even the boys were dressed in my clothes. They would come raid my closet. And, of course, the girls would be wearing the boys’ things. That’s why I made separates—it was just pants and T-shirts and shirts and skirts, and every one could come over and mix and match.

Seems like the clothes would get ruined with all that partying. Oh yes, they would. That’s true. Dancing, sweating. Knits are so perishable, you have to be careful with them. But it’s the body that goes in the dress that gives it life. And I was always making new things, so it didn’t bother me. I had so many things, I couldn’t keep track of them all.

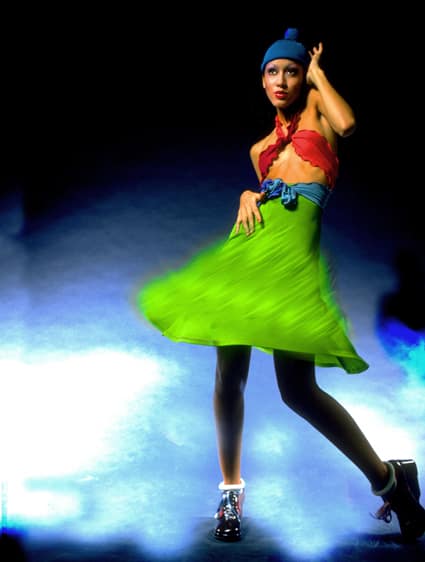

[caption id="attachment_252182" align="alignright" width="425" caption="Pat Cleveland in top and skirt with lettuce edge finishing, 1972. "] [/caption]When you showed at Versailles, what made your show so different from the ones by the more formal Paris designers? I don’t remember all the clothes. I just remember the models strutting. It wasn’t necessarily dancing; it was voguing, before people knew about voguing. I told them to walk to the front of the stage after they were all out there and then just to pose. And move. And people loved it.

[/caption]When you showed at Versailles, what made your show so different from the ones by the more formal Paris designers? I don’t remember all the clothes. I just remember the models strutting. It wasn’t necessarily dancing; it was voguing, before people knew about voguing. I told them to walk to the front of the stage after they were all out there and then just to pose. And move. And people loved it.

Did you get to meet any of the French designers? Yes. [Yves] Saint Laurent told me my clothes were beautiful. He was very shy. He didn’t speak English, but he was friendly. He told me in French that my clothes were ravishing. It was a great compliment. And then we met Josephine Baker. She was watching our dress rehearsal and told us that we looked fabulous, and that she was so proud. Of course, that was in French, but they interpreted it for us.

The book touches on your role as one of the first important African-American designers. Is that something that you think about a lot? No, not at all. I’m just a designer who happens to be African-American. That’s other people that think about those kinds of things. I was kind of anti-political—or, I didn’t get involved with politics. I didn’t want to know about the war. I had asthma, so I couldn’t do anything about that anyway. But, of course, you are affected by everything that happens in your environment, so I just hope the best parts came out when I designed. It was all about freedom in clothes, and freedom in living, freedom in loving. It was all about freedom.

Do you still go dancing? Yeah, but the clubs aren’t the same. They’re not. It’s a different time. I just remember how much fun we had.