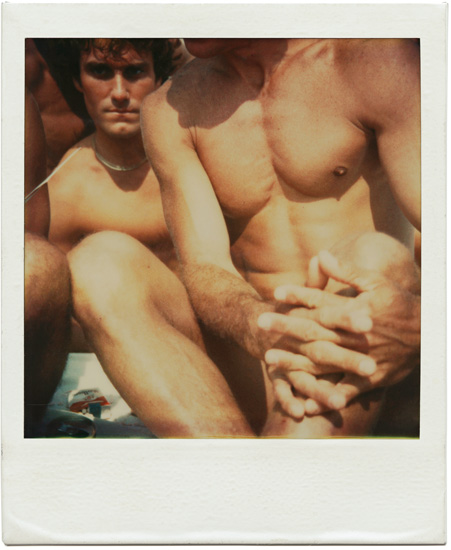

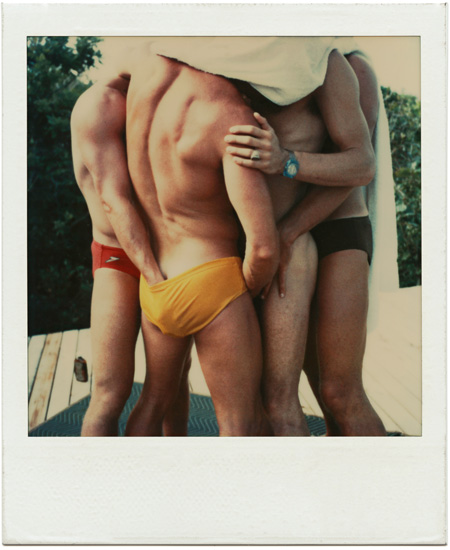

Tom Bianchi spent the '70s and early '80s shuttling back and forth between Manhattan and Fire Island, an idyllic gay vacation spot about 60 miles east of the city on the south bay of Long Island, where he partied, tanned on the beach and, as you can see in his new book of photos from the era Fire Island Pines: Polaroids 1975-1983, made friends with lots and lots of very beautiful people. Not originally intent on becoming a professional photographer, Bianchi started playing around with a Polaroid SX-70 for fun and began to realize that his daily life—filled with romance and friendship and impeccable naked bodies—might be something worth documenting, a magic moment of exploration and liberation that was an important step away from the repressed midwest of the 1950s and 1960s in which he was raised. As it turns out, it was a fleeting moment, too: the gay sexual utopia that flowered on Fire Island, an island that felt far away from the prying eyes of a mainstream American society that still labeled homosexual acts illegal, would be tragically cut short by the onslaught of AIDS. Thirty years after the last photo in this book was taken, Bianchi spoke to us about his life on Fire Island, and why beauty is so important even if it's marred by a whole lot of sadness. Pick up a copy of the book here.

How’d you get started taking these photographs? I never set out to be a photographer, I set out to be an artist. I wanted to paint, sculpt, make beautiful things, have a cool time. But I started playing around with cameras, and I realized that photography was, every bit of it, a very personal diary. The best advice I ever got about what I was doing came from Robert Mapplethorpe’s boyfriend Sam Wagstaff. I was showing him some of my pictures and some of the things I thought were very coolly composed and had artistic coloring, and he was poo-pooing them. He said, you can't compete for color with everyone else, but you've got one thing that no one else has: you have the uncanny ability to take us behind the doors of you and your friends' lives. Make your pictures about that. That's what’s going to be interesting in hundreds of years. And he’s right. I'm interested in conceptual art and all of that, but it seems to me not so interesting as pictures of life. Because the lessons that we need to learn, to have a fulfilling life, come from other people.

How’d you get all these people to just take off their clothes for you? They know that they’re going to be honored and respected in the way they’re imaged. And that’s what allowed the Fire Island book to happen, because back when I was taking those pictures, a lot of people were very nervous about the possibility of being outed by a photograph. You’d lose your job back then if your employer found out you were gay! So to win them over, and to persuade them that it was okay to show ourselves to the world, I had to show them how beautiful I saw them.

How’d you get all these people to just take off their clothes for you? They know that they’re going to be honored and respected in the way they’re imaged. And that’s what allowed the Fire Island book to happen, because back when I was taking those pictures, a lot of people were very nervous about the possibility of being outed by a photograph. You’d lose your job back then if your employer found out you were gay! So to win them over, and to persuade them that it was okay to show ourselves to the world, I had to show them how beautiful I saw them.

As a 26 year old, I look at your book and books like this, nostalgic books about the past, whether it’s Patti Smith’s book or yours or any other, and think, I wish I was born then. Now sucks, comparatively! Was it really that great? We did have fun, yes. But Fire Island was, for me, a little utopia away from everything. It’s literally an island. And even for me, my photos were an idealization. I was born the same year that homosexuals were still in German concentration camps. In the city that I grew up in, Chicago, homosexuals were commonly targets for police scans and arrests for lewd conduct and all sorts of stuff like that. But things in New York were freeer. Stonewall happened right before I got to New York and shortly before I started doing all of this at Fire Island. The image of the homosexual was that of degenerates working in shadows and perverts trying to seduce children. So healthy young American boys playing on the beach? Early game changer. I wanted my own mom to see it and be like, Oh, these are like the nice boys that you grew up with. Basically I saw myself as the supporter of and encourager of the whole gay consciousness that was emerging at that time in a very positive way.

But what I want is for you see in the book a template for the way things can be. That's what we came up with on how to live a beautiful life. You guys can make your own version of that. Do it consciously, do it with fun, do it beautifully. And just enjoy the hell out of the experience. It's yours to create.

Is there a photo in the book that’s particularly important for you? On page 70, of my best friend Freddy. At this point in time I was transitioning from being a corporate lawyer to being an artist, and Freddy was sort of helping me lose the preppy side of myself. For Freddy, his beauty was a throwaway, in the sense that he wasn’t cultivating it, plucking his eyebrows and all that shit. He would do silly stuff, get a pair of high heels, or whatever. But this photo really expressed, for me, the spirit of who were were, what we were about. What’s special about it is remembering the affection that we all had for each other. We were all best buddies. We played together, we partied together, we adored each other. We danced with each other.

Is there a photo in the book that’s particularly important for you? On page 70, of my best friend Freddy. At this point in time I was transitioning from being a corporate lawyer to being an artist, and Freddy was sort of helping me lose the preppy side of myself. For Freddy, his beauty was a throwaway, in the sense that he wasn’t cultivating it, plucking his eyebrows and all that shit. He would do silly stuff, get a pair of high heels, or whatever. But this photo really expressed, for me, the spirit of who were were, what we were about. What’s special about it is remembering the affection that we all had for each other. We were all best buddies. We played together, we partied together, we adored each other. We danced with each other.

You say in the foreword that so many of the people in this book have passed away from AIDS—what is it like going through these photos now? I have a pretty good memory of every one of these experiences, so it will take me right back. For example, right now I’m looking at page 126. On the left-hand side it’s a diptych, and there’s like four guys just goofing around being silly with a towel over their heads. I remember that afternoon and the playful spirit of it completely, just completely. The photographs on the other page, the man in those photographs was somebody I had met on the dance floor was clearing at the Ice Palace one day. I just looked over and I saw this beautiful guy. He was great spirited and we had a very short time together, but made some very beautiful real photographs.

What was Fire Island like during the AIDS crisis? The demographic of that disease in the Pines was beyond imagining. Literally you would hear that an entire house, 6-8 guys, all of them had died over the course of the winter. That was not an uncommon thing. There was a particular day I remember when I was walking down the beach and every friend I encountered said, “Did you hear about....” And it was always a hospital admission, a death, pneumonia, something. In those days, whatever that something was, was a death sentence. Nobody, nobody survives. It was a 100% death sentence. I wonder today how I could have held it together, given what my life became, because life became endless visits to hospital room, endless memorial services, and being witness to things. A lot of us were still in our 20s—a pimple on our forehead could wreck Saturday night. Imagine children going through the development of debilitating diseases which robbed them of everything. Mobility, looks, sight, often hearing. Do you remember Sherri Lewis who had the sock puppet Lamb Chop? I saw her on a talk show once and when she was talking about a very difficult medical prognosis that she had been given, she said the only way I knew how to handle this was to behave the way I thought a very strong person would behave. And so that’s how you go through that experience. And that’s what I did.

Do you go back to Fire Island? Yeah, regularly. My old housemate, we had a house together for many years out there, and he still owns the house that we lived in for many years. And so when go back to the Pines, my pictures are still on the walls, and the house is pretty much as it was in 1980. It's like being able to go back to your childhood home. And you still have your room.

Do you go back to Fire Island? Yeah, regularly. My old housemate, we had a house together for many years out there, and he still owns the house that we lived in for many years. And so when go back to the Pines, my pictures are still on the walls, and the house is pretty much as it was in 1980. It's like being able to go back to your childhood home. And you still have your room.

I want to ask you about age—there’s an idealism to the photographs in the book, and how people and bodies look when they are young, so I’m curious how it’s been for you to get older. I suppose I have to say I'm finding this a shocking experience. A big part of that is because of the man who has a lover, Ben, who is 29 years younger than I am. We have a super intense romantic relationship. More than any other relationship I've ever had in my life. And I'm fucking 67 years old. I wonder, how the hell did this happen? Because I was supposed to be retired, over the hill, invisible, etc. But so much of this is all expectation, and my whole life has been about, let's not live by negative expectation. I’ve learned a lot. And a lot of what I learned was to accept my good fortune and cultivate it.

One of the remarkable things about the book is kind of how it feels like Instagram before Instagram was invented. Your work kind of predicts internet exhibitionism, showing off your friends, your self, your vacation. You're looking at what would be the Abacus version of the computer. But I think exhibitionism is a healthy thing. If you have high self-regard, play with yourself, put yourself out there. You'll be so much more free and healthy for it. I've always said you have to find something that you think is a little scary and you're not sure you would be comfortable doing it, and then that's the cliff you throw yourself off. What's the downside? Well, maybe you get more dates on Saturday night. And smile while you’re doing it.