Listening to Drake with a neutral facial expression

The very first review of Nothing Was the Same I encountered was when, the morning after it leaked, someone asked a coworker what they thought and they shrugged and said, "It's boring." By then, I was a solid three listens in, and "boring" hadn't once occurred to me—it hadn't occurred to me in my life, probably, regarding Drake. Subsequent listens to the album, though, have involved me wondering if perhaps its boringness is exactly why I love it. Now, when Drake calls the record Nothing Was the Same he’s presumably referring to his life post-fame and post-fortune, started vs. here. But it’s just as easy to read the sentiment through the prism of my own life—nothing was the same after I was denied a bank loan this summer, nothing was the same after my girlfriend took a job that demands her every waking hour, nothing was the same after we had to move. Yet, judging by the narrow emotional range of Drake's voice as well as the range of beats he employs on Nothing Was the Same, we've responded to very different changes in a similar way: flatlined, drained, voicing emotions but, in delivery, unfazed. It reminds me of nothing so much as one of Tao Lin’s favored descriptors—“neutral facial expression”—used a dozen times in each of his last novels (example: "They made funnel cakes for about three hours and then walked to different areas of the carnival, sometimes saying 'cheese beast' or 'party girl' quietly while facing forward with neutral facial expressions").

Nothing Was the Same is, sonically, pretty damn even-keel. There's no uptempo Rihanna feature, nor is there a song where she'd make sense. The album is not so much lacking in energy as restrained in the face of, say, the loud-mouthed Yeezus, as if Drake were conserving himself for the non-musical parts of his life, or were already spent before he got in the booth. He sings less than ever. When he raps, he usually emphasizes the same note over and over, then he'll raise or lower his voice by a note or two, always keeping within a very narrow melody—AAAAAABAAABA, or something like that. At least 80 percent of the record is delivered in the exact same voice, that slightly airy Drake tone that sounds like he's projecting words across the roof of his mouth, which comes across as very direct and unaffected. There are no real explosive vocal moments on Nothing Was the Same—Drake raises his voice a few times, but rarely enough to change how it actually sounds. On the quieter, more somber end of the album, those parts are outsourced to Jhene Aiko and Sampha, or hidden within the handful of guest monologues, like Baka's outro to "From Time," his speaking voice seeming somehow more emotional than Drake's on the song. Maybe it's because Baka is talking over just a piano, an emotive, instrumental accompaniment that Drake very rarely, if ever, surrounds his own voice with, but Baka's tone expresses more unhappiness talking about Scarborough than when Drake says actually unhappy things like, I've always been feelin like she was the piece to complete me, or raps about his strained relationships with his father. Maybe the tonal flatline to Drake's voice is because there is a degree of narcissism in his music. Drake seems to be making music about Drake for Drake, for us to look in on and admire—because why would he raise his voice, or sing, to himself?

Yelling online, monotone IRL; Drake drops tears on the lyrics pad, delivers them like he’s ordering a bagel.

The beats are similarly reserved. The crawling, Detail-produced "305 To My City" has one of my favorites, because of the bizarre treatment of some instrumental sample that has rendered it almost exactly like the sound of wind over snow. It's as though Detail has taken an entire recorded band and made it sound like dead air. Boi-1da's "Language" takes a similarly deflating approach, with a filtered synth that continually reappears and then ebbs away, like a rave that never pops off. "Wu-Tang Forever" features a distinctive piano, sampled from Zodiac's dismal "Loss config.," but it's treated in a way that makes it difficult to envision anything but a robot at the piano. In each of those songs, as with most of the album, the percussion is very spare, essentially driven by one kick and one snare. I think that's a key trait of the music on Nothing Was the Same: it doesn't sound like a person is playing it; it's just playing. Even "Own It"’s repeated, Auto-Tuned own it, own it, own it that pops in at 1:40, probably the entire album's most striking production flourish, very The-Dream-like, is for the first 14 utterances just the same single note on repeat, no melody or harmony.

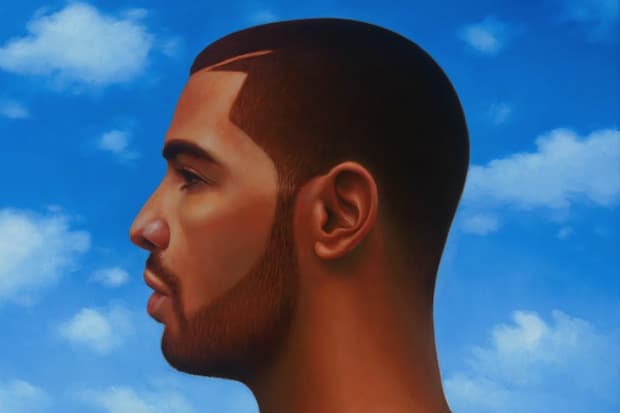

So, all of that flatlining sounds to me like Drake’s music is making a neutral facial expression. By contrast with his beaming and flirty interviews, on this album I picture Drake rapping a neutral face, and I listen with one. He certainly wears one on the cover. Something about the phrase "neutral facial expression" in my mind magnetically bonds Drake to the millions of young people with smartphones, to an entire swath of internet-addled over-sharers lacking patience. Drake’s delivery reminds me of the old internet cliché of people ranting and raving online, and expressing all of this in emotive words, but physically, outwardly being stone-faced, desensitized. Yelling online, monotone IRL; Drake drops tears on the lyrics pad, delivers them like he’s ordering a bagel. Or, better yet, to clarify what I mean by “the face”: what universal feeling exists today if not the shared experience of self-awareness upon seeing your neutral expression on a screen in the moment before you take a selfie, of confronting your crude state pre-posing and posting, looking plain and without a mask yet on? Maybe that raw feeling, more so than actual sadness, is what Drake has always been out to channel: rap without a mask on. I don't remember if Drake has rapped about selfies, but he's certainly talked around the general troubles of life via digital devices, like I guess my text didn't resonate on "Too Much," or with this better bit, circa 2010: I got an email today/ Kinda thought that you forgot about me/ But I wanna hit you back to say/ Just like you, I get lonely. I think about it a lot, the "just like you." Obviously, expressing sadness/loneliness in order to be relatable has been a big part of Drake's M.O.

I think you can apply to Drake's new album a phrase recently used to describe a quality of Tao Lin's writing: "it simulates the bogeyman of mediated affectlessness that haunts every millennial." Lin uses very different narrative strategies than Drake—Lin's is third person, the rapper's first person; the former mostly disavowing introspection, the latter emphasizing it. Lin writes in unrelenting, to-the-minute present tense, while Drake's "started from the bottom" pose requires constantly revisiting his past as a point of comparison. And where Lin's style seems to emphasize the rift and estrangement between the reader and Lin’s characters, Drake's choices of language serve largely make him more relatable (Grantland's Steven Hyden credits Drake’s style of self-examination with understanding “that the public ultimately prefers the fantasy of accessibility to the fantasy of sequestered opulence”). But I see the works of both artists as like two sides of the same coin, pictures of contemporary young adulthood. The quality of affectlessness in Drake, created by his flatlined sonics, like Tao Lin's prose style ("If I do affectless prose," he said in 2009, "I want to do in the extreme"), is in my opinion the same quality that makes people peg them as spokespeople for their generation. So whether Drake and Lin are consciously speaking for a swath of Facebook users, narcissists, personal branders, etc. (an idea interrogated in David Drake's Complex essay), the fact is that their subjective, semi-autobiographical narratives function that way for critics.

The word "millennial" has been used in recent Drake stories in Complex, Grantland, Variety, MTV, Billboard, L Magazine, Gawker, Buzzfeed, The Detroit News, Flavorwire; it's been used in reviews of Tao Lin's Taipei easily as many times, on our own site among them. And once you start looking for comparisons between Tao Lin and Drake, a lot of writing about the one can be easily transposed to describe the other. Jon Caramanica, writing about Nothing Was the Same for The New York Times, said, "There is a way Drake cuts through the structures of language that people create to better capture their emotions but really end up as hindrances." Tao Lin's "autistic" prose, devoid of qualitative language, is similarly direct. In Steven Hyden's Grantland story, he describes Drake's as "the language of tweets, Tumblr posts, and Facebook timelines—the lingua franca of a generation… most appreciated by those who speak it fluently,” much in the same way that The New York Observer’s review of Tao Lin’s Taipei was titled “Gchat Is a Noble Pursuit: Tao Lin’s Modernist Masterpiece.” Just one more example: Pitchfork's Jayson Greene writes, "Loneliness, self-afflicted or otherwise, has always been Drake's most reliable fuel," while a 2010 Salon profile of Lin claimed that "Where Lin is coming from, and what his readers share, is a sense of loneliness." It goes on and on. I think at the core of their overlap, and the overarching quality that makes them seem to speak for so many people, is that their work gives the impression of a neutral facial expression. Somehow this makes sense to me. Drake and Tao Lin: weird and unwitting partners, mining the tension between what you feel and how you express it.

So, to summarize: I listen to Drake with a neutral facial expression. On Nothing Was the Same, Drake uses a flatline, neutral voice. He raps on flatline, neutral beats. And I don't know if I'm a millennial or what, but like Tao Lin's last book, Drake's last album really resonates with my flatline, neutral life.