TWO NIGHTS AT THE CHURCH OF KANYE WEST IN NEW YORK

Yeezy season has officially passed through NYC, leaving a frigid cold front and slew of unforgettable, Auto-Tuned speeches in its wake. I attending the opening and closing nights of the tour's New York stint, which stretched across two weeks and four surreal shows in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Kanye West riffed on Alejando Jodorowsky, Lenny Kravitz, Def Jam and Disney, but the biggest quote I took away didn’t come from West himself. Rather, it was a dusty, pitched-up sample from “On Sight,” the kind that the rapper has been using to articulate his thoughts since he first crashed through the wire almost a decade ago: He’ll give us what we need, it may not be what we want.

That lyric may define the Yeezus tour and Kanye’s career altogether—it’s become clear that a lot of people don’t want what Kanye is currently giving. Yeezus garnered the lowest opening week sales of his career. Attendees allegedly walked out of some early tour dates, before a road accident led to the outright cancellation of several Midwestern shows. He’s severed ties and hinted at losing deals. A quick scan of any comment thread related to the rapper reveals the hivemind's opinion: Kanye’s an egomaniac, and crazy. But in a city like New York, which for generations has been a haven for cultural agitation and corporate appropriation, the Yeezus tour's sermons resonated powerfully, lamenting the tension between art and commerce, and the racial dynamics that have engulfed hip-hop's central position in pop culture. He's torn between the responsibility to teach versus the burden of explaining: "When I call myself a creative genius, it's not a compliment, it's a burden," he vented in Brooklyn. At Madison Square Garden, he honed in closer: "I envy likable people. I envy manners. The only difference is... I'll turn up on these niggas."

Tuesday’s Kendrick Lamar and Sunday’s A Tribe Called Quest were a striking pair of openers, one rap’s ever-ascending prodigy and the other sacred elders riding off into a self-imposed sunset. Both Kendrick and Tribe have taken the slang and symbols of a local community and made them palatable to the world. Footage of Compton swap meets and droopy Blood-walks was projected behind Kendrick and his live band, making LA’s notorious hood look as beautiful as it sounds on his breakout album, good kid, m.A.A.d city. And Tribe’s “last” show—which, judging by Phife Dawg's conservative stage-presence, may in fact be its last—revived the quirky, flirty, eccentric spirit of early ’90s Queens. Their stage backdrop included kids literally tossing around a sign that read “n-word” during “Sucka Nigga,” and a body-painted Bonita Applebum flaunting her 38-24-37 frame through Times Square and across the stage. Kendrick has toured exhaustively over the past year and has a sharp, seasoned stage presence, but his live band somewhat drained the potency of his beats. Thumpers like “m.A.A.d city” and “Money Trees” relied on the participation of an enthusiastic crowd to maintain their menace. Tribe faced a different challenge, as Q-Tip rallied unfamiliar concertgoers to get out their seats and for Phife to stay on beat. Jarobi played middleman as the crew bounced through classics like “Oh My God,” “Buggin’ Out” and “Electric Relaxation,” but it was Busta Rhymes’ infamous cameo during “Scenario” that brought the Garden to its feet. Kendrick and Tribe are both iconic in their own right, but the massive mountain that shadowed them throughout their sets implied what was to come.

"When you go in the studio, you watch your mouth, cause you don’t want to lose that house."

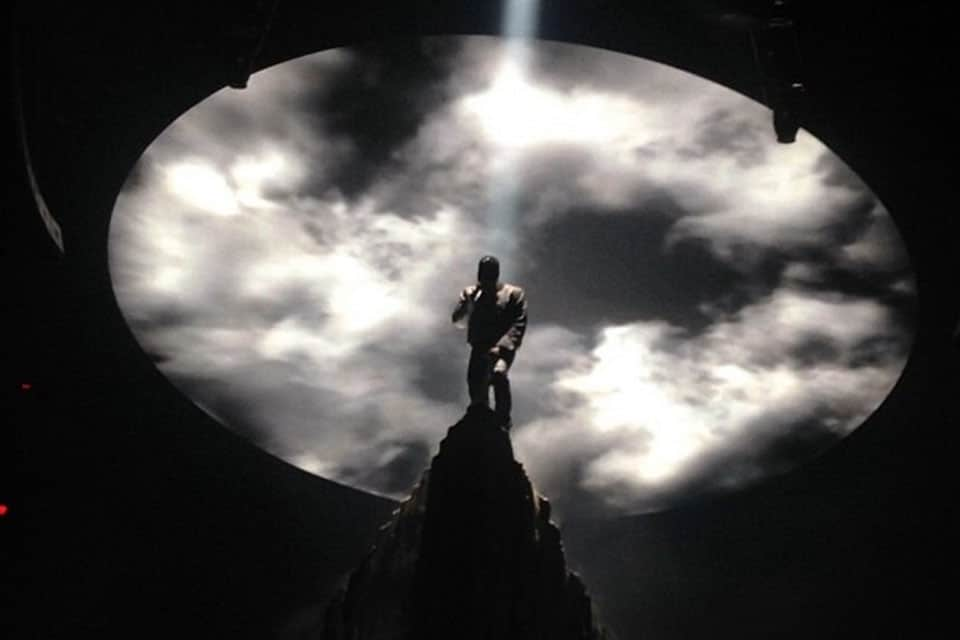

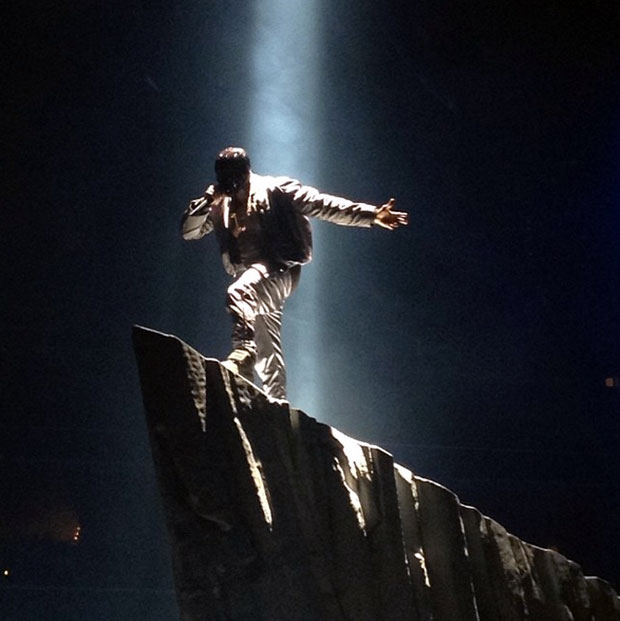

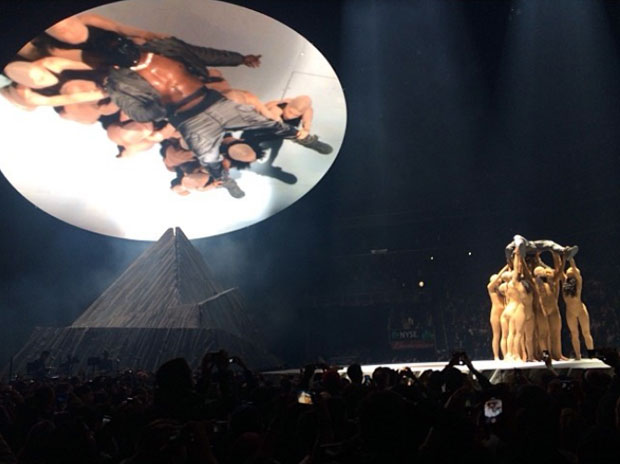

Kanye's Yeezus set is split into five spelled-out movements: Fighting, Rising, Falling, Searching and Finding. Fighting’s “New Slaves” and “Mercy” find him punching at the glass ceiling and demanding 50 mil from Def Jam. He alludes to Malcolm X and M.O.P through Rising’s “Power” and “Cold,” and shouts from a literally rising mountain peak on “I Am a God.” Falling marks the dark turn of his mother’s death, as a wistful snowfall starts during “Coldest Winter” and a red-eyed demon stalks him from a distance during cries for help like “Hold My Liquor” and “Heartless.” “Blood on the Leaves” drags the crowd to the depths of hell, with bursts of fire and pulsing red projections surrounding the manic ode to lynching, abortion and the implosion of the black family structure. The narrator that introduces the show’s Searching section promises, “If you seek him, you shall find,” before Kanye launches into “Lost in the World” and explains, “This song is about two things: One is when I first moved to New York, and the other is an email that ended up as a poem. That email was to my fiancée.”

This search is also where his infamous rants land over the minor chords of “Runaway.” Famous for their absurd name-drops and self-proclamations of genius, I’d argue that Kanye's speeches are sourced not from hubris, but self-pity. “If you’re a musician, you sign a deal with a corporation so you can buy a house. And when you go in the studio, you watch your mouth, cause you don’t want to lose that house,” he explained Sunday, sounding hoarse and nearly deflated. “But when they write the history books, they won’t write what house you had. They’ll write what impact you had.” How does one balance massive influence with dependence on label execs? How do you give the people want they want, knowing very well what they really need? West’s onstage assertion that CEOs and fashion gatekeepers have told him to “Shut up, nigger!” may be laughable to some, but when was the last time we heard Michael Jordan—the only prominent black figure with a comparable apparel deal and cultural relevance—really speak? “I’m sorry if I’m going on too long,” Ye sighs before sulking back into his mountain at his rant’s close. “I know y’all just want to hear another hit song.”

Of course, no story is complete without a happy ending. The show's concluding movement, Finding, chronicles the Kanye fans grew to love, the "old Kanye" so many clamor for, when his battles were more relatable and his sounds more widely digestible. Classics like “Stronger,” “Through the Wire,” and “Diamonds from Sierra Leone” arrive bright and exhilarating, and yes, White Jesus himself gives his blessing before West launches into “Jesus Walks.” “Don’t nobody look stupider than me,” Ye confessed with a laugh to his flock after victory lap “All of the Lights” on Sunday. “So if I can say my stupid dreams, you can too.”

Though it was only five months ago, it feels like it’s been ages since West shocked the country on Saturday Night Live, his album-launching "Black Skinhead" performance a raging, wide-eyed decrying of racism, classism and corporate greed. Since then, he’s taken nearly every definitive symbol of America’s culture and history—purple mountains, “Strange Fruit,” the confederate flag, the holy cross, black slaves, White Jesus—and dragged it through his dark, twisted filter, reflecting back to us the best and worst of ourselves. He’s risked his career to say what he feels, and he’s bet our Ticketmaster accounts that we are willing to hear it. For the past week in New York, he’s shouted up to the boardrooms we don’t see to plead the causes we can’t voice. Time will tell whether he’s been heard. Jesus died for our sins. Yeezus just rose again.