My Rules: Glen E. Friedman on Fuck You Heroes and Making Art for Art’s Sake

The iconic photographer dishes on youth culture and rebellion ahead of the release of his new book, My Rules.

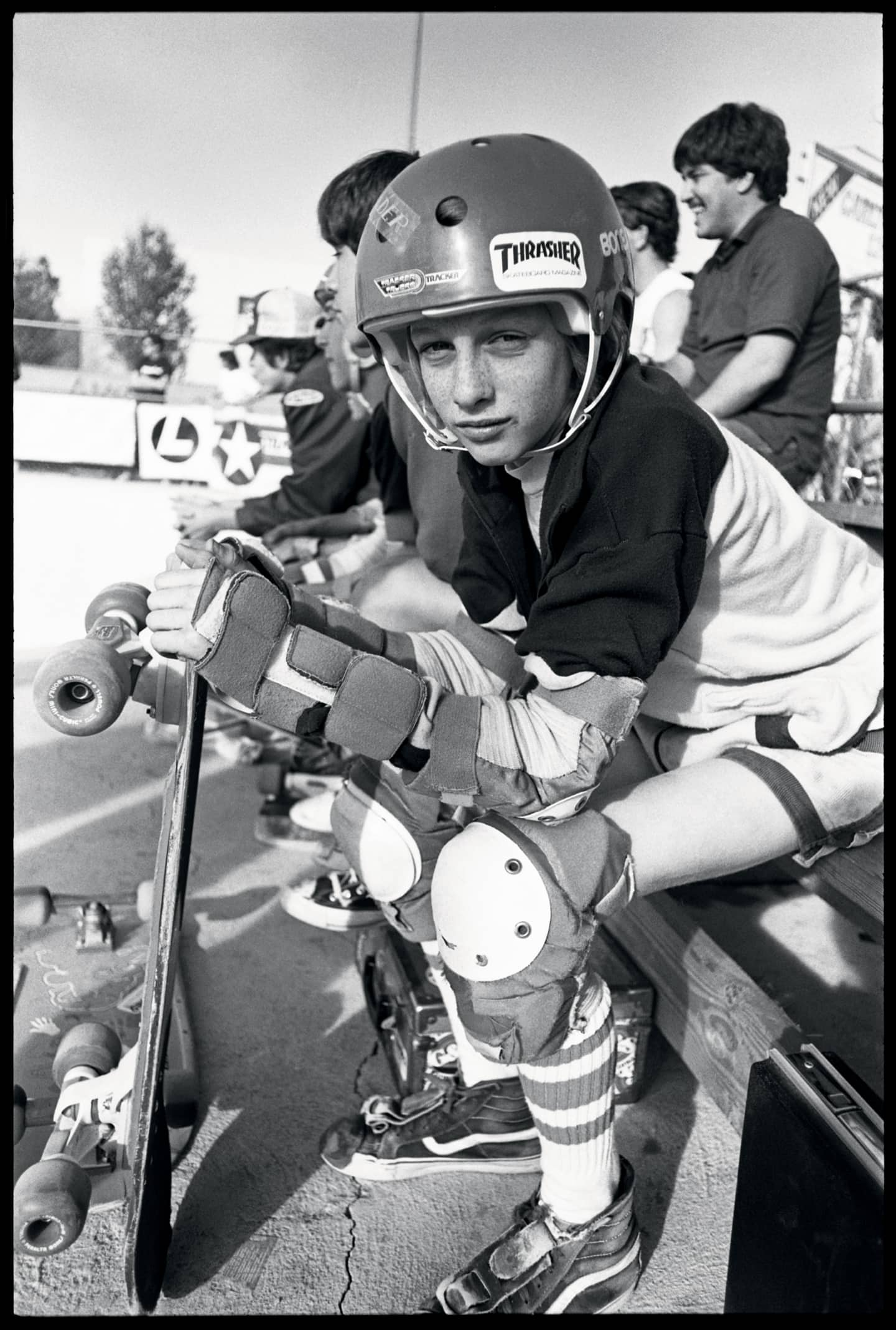

Glen E. Friedman is a self-proclaimed "Fuck You Hero," the human manifestation of a middle finger to the system. From the age of 13 and for the past four decades, the North Carolina-born photographer has tirelessly documented some of the most important cultural movements in recent American history, from the rise of skateboarding to punk rock's prime to the early days of East Coast rap.

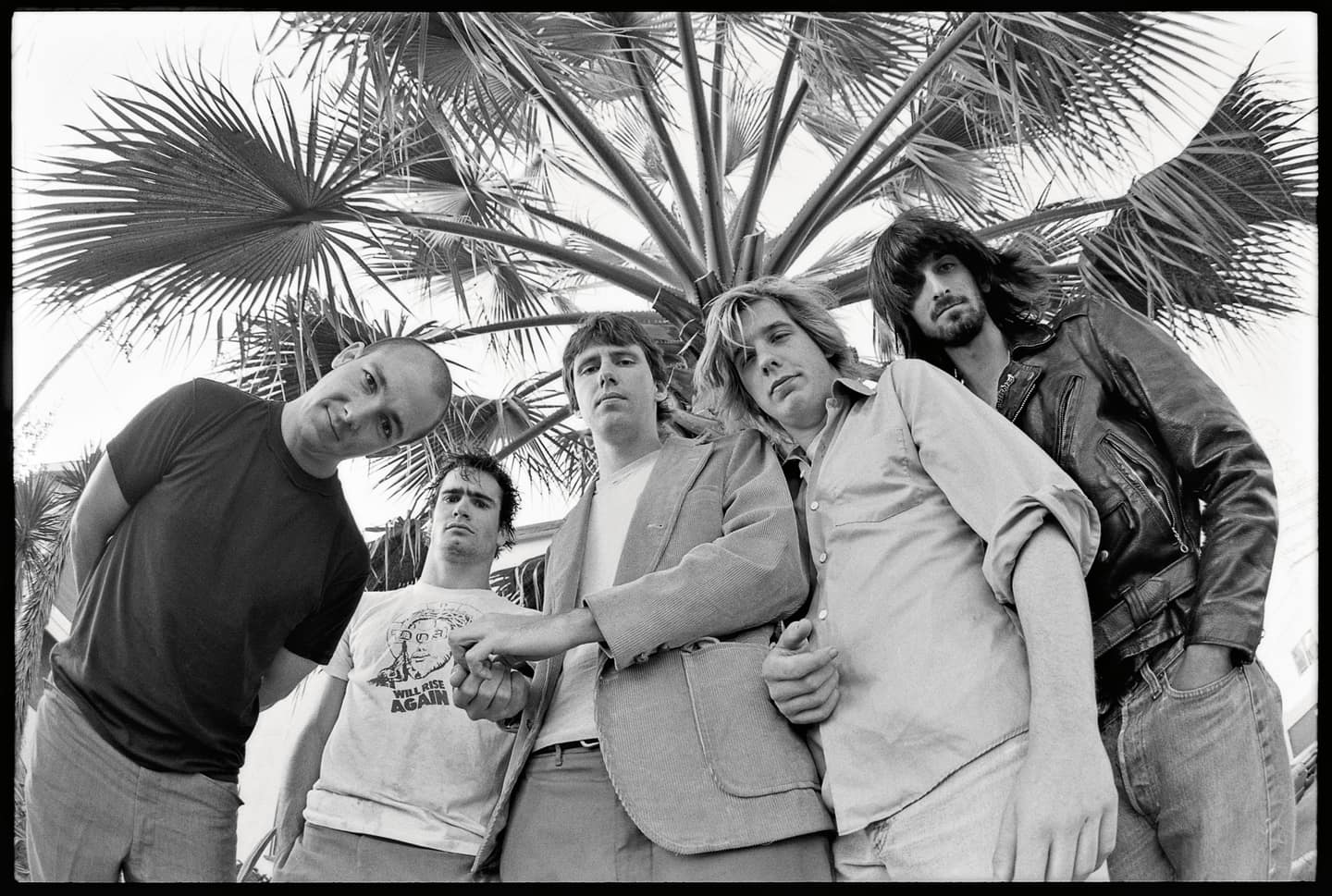

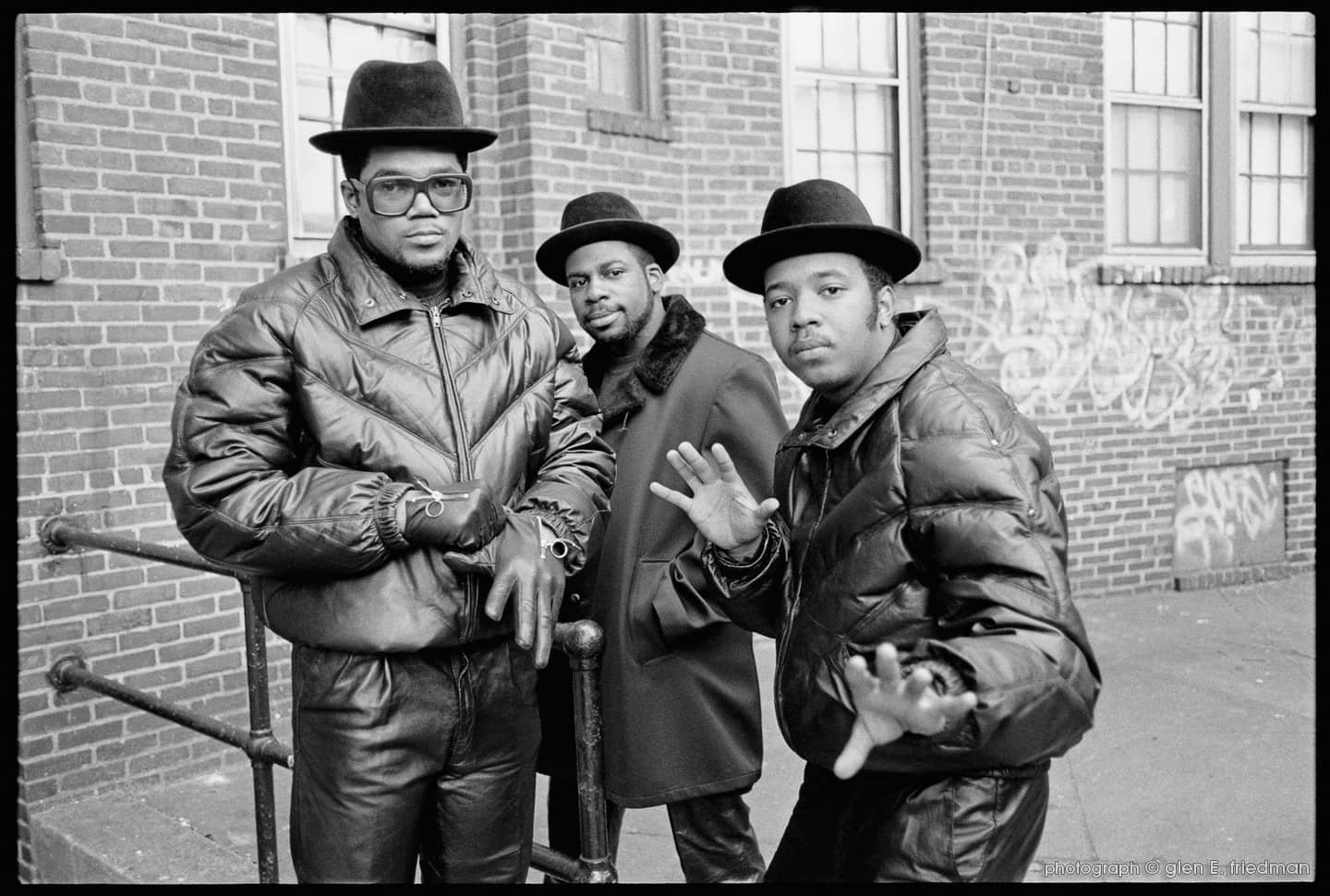

In '82, Friedman splashed onto the global scene with his debut photozine, My Rules, a lo-fi, in-your-face collection that introduced intrigued youth from across the world to the stateside happenings that would later pave the way for grunge, metal, and rap. Since then, he's published six books, including the seminal Fuck You Heroes and Fuck You Too, shown his work in countless exhibitions, been inducted to the Skateboarding Hall Of Fame, and snapped some of the most recognizable portraits of music's most trailblazing faces, including the above portrait of Beastie Boys from 1986. Friedman's also remained an outspoken political force, openly supporting Occupy Wall Street and snapping photos of Russian punk heroes Pussy Riot during their short trip to New York earlier this year.

This week, the iconic photographer adds to his legacy with his seventh book—and debut with a major publisher, Rizzoli—which bares the same name as his debut 'zine. Weighing in at seven pounds and featuring 100 never-before-published photos as well as essays from Rick Rubin, Shepard Fairey, Ad-Rock, Henry Rollins, and many more, My Rules is a stunning, 324-page time capsule of counterculture's most revealing moments, serving as a bible for youth in revolt looking for honest inspiration. Friedman spoke with The FADER last week as he geared up for today's release of My Rules, and over the course of an hour he passionately discussed the evolution of his style, the regression of youth culture, and the importance of creating art for art's sake.

The release of your new book coincides with the 20th anniversary of Fuck You Heroes, so let's start there. It was your first book and a collection of photos from 15 years of your life that spanned the Dogtown days, punk's prime, and the beginnings of hip-hop. Do you remember what your mission statement was with that book? At the time, there were a lot of weird things going on. If I remember correctly, there was a lot of wack hip-hop records coming out, skateboard wheels got really small and hard, and punk rock had gone generic and was not that interesting for the most part. So I thought, while these times were still fresh in my head and these images were still inspiring to me and some other people, I should get a book out to show people where it all came from and what the fuck was going on that started these things in the first place.

What was the significance of the title to you then? Were you saying fuck you to the people you'd photographed or to the new wave of people who were ruining the things you loved? Well Fuck You Heroes, to me, was a book of heroes that were heroes because they said "fuck you" to the establishment and everybody around them that tried to limit their thinking and their ideals. Therefore, they're heroes. Just like you might pick up a book of American heroes, this is a book of Fuck You heroes.

A big part of how you were able to capture these major movements was by infiltrating and becoming a part of the communities you photographed. Why do you think people let you in and trusted you to document their lives? In the skateboarding days, I skated. Those spots where the guys rode, I was a local at those spots. So just by being a local, I got to know a lot of the guys and I thought it was important to start taking pictures. Things were going on that I wasn't necessarily seeing in the magazines yet. The magazines were about four months behind, so when you see a picture, it was taken four months earlier than you'd actually see it published. I also happened to take a photography class at school, and so I just started taking pictures with a little pocket Instamatic…

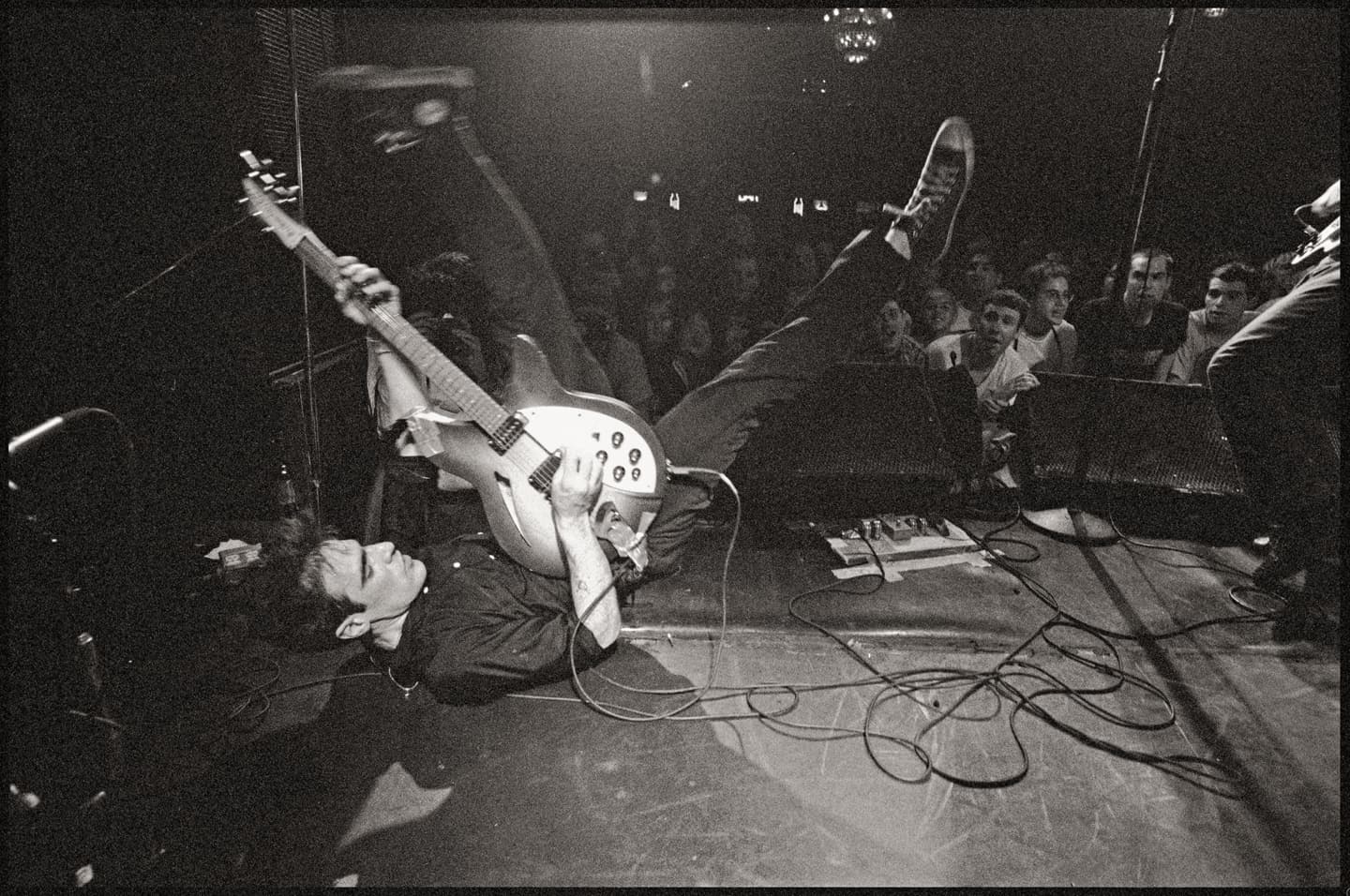

In early punk rock stuff, a lot of those guys skated so they knew me from there. I got some respect immediately because of that, but also they saw that I had a knowledge and an interest that was on the same level, if not exceeding, their own. I was very involved and I loved it. It was vital to my life. I was just as interested in it as the bands were.

And when it came to hip-hop and meeting those rap artists, I think most people early on were kind of surprised, but again it was something I was very into. Maybe because I was white, some people might've been a little bit surprised, but many people in the punk community were very into hip-hop early because it was just another rebellious music form that we all thought was exciting.

"I lived for skateboarding, I lived for punk, I lived for hip-hop."

What connection do you see between skate, rap, and punk? What do you think made them all rebellious forces in the face of popular sports or pop music? What was really important about these three things is that they were all almost exclusively youth-generated. There were no parents to tell you how to skateboard or where to ride, it was something the youth did on their own. There'd been skateboarding in the '60s and the '50s, maybe even in the late '40s, people rode around on 2x4s with roller-skate wheels on them, but where it got at that moment could be compared to nothing else. It was exclusively youth-generated, as was punk rock. American punk rock, at that point in time, had nothing to do with major labels. The Ramones and B-52s, that was incredible and it was artistically revolutionary, but the next wave, it was a very young thing. These are like teenagers, man, and they were playing music that was so simple and so exuberant because of the energy we all had because we were just so incredibly young, and a lot of people were straight-edge. People had a lot of fucking energy and excitement. They weren't pulled down so much by alcohol and drugs like many people who came before them, and many became later as they often did, who got into music. Not getting high, smashed or wasted, it made a difference to have a fucking clear mind. Now, you take that to hip-hop, and it's very, very similar. There was rap for years before it blew up, but when the records and the techniques really started going crazy was like in the mid-'80s, when it was like, okay, now it's become its own thing. It's not just derivative of dance music, it's not only an answer to rebel against disco, it's really its own thing. All the sudden the lyrics became rebellious. They all took it to another fucking level. To a really hard place. A hardcore place. That's what I really appreciated. And it was exciting, and new, and like nothing else.

You started taking photos when you were 13. How deliberate was your style then and how did it evolve over the years? When you start so young, you're very pure. I was reading National Geographic and Sports Illustrated regularly as a kid, and back then, those magazines were the pinnacle. Besides that, I grew up with a very creative mother, so I was exposed to a lot of art. I think I had an understanding of really high-quality work, whether it was from reading those magazines or reading about the Renaissance painters and masters, there was a lot of good influence around me. Now, when I was a youngster starting to take these pictures, that's in the back of my head. And in the front of my head is the subject matter that I'm very close to. So, when you are basically classically inspired, but you're also totally involved with what you're photographing, I think it'll come out in the work. I wasn't a voyeur just taking pictures of something I thought was interesting. I was living these things, it was a part of my lifestyle. In fact, it was vital to my very existence as a teenager. When you're a kid, there are things that you live for. I lived for skateboarding, I lived for punk, I lived for hip-hop.

You've taken some iconic portraits over the years, from Run-DMC in Hollis [below] to the Beastie Boys at Washington Square Park. What's your approach to getting artists to a comfortable place where their personality and character can shine through in a photograph? That's very, very easy, and that may be one of my simple first lessons if I was to teach a photography class: I went to where people were comfortable. I went to their neighborhood. I went and hung out with them, and asked them where they would like to hang out. Where do you feel cool? Where do you want to hang out? When I do a photo session, I'm all in. I don't even need to fuckin' eat. I would like to, but if you don't wanna eat, I don't wanna eat, I wanna take great photos. What we do is we go out and we do good work. So I speak to the artist, "Where do you feel comfortable? Where would you like to do this?" Then I say, "This is where I would like to do it. This is what I think. Let's walk around, let's hang out." It really disturbed me, when I started to shoot hip-hop, that so many people took rap artists to the studio. To me, it's all about the person and their environment… I don't know if it was because [other photographers] were afraid to go to the hood or that just wasn't the way they photographed, but as far as I was concerned, taking rap artists and putting them in a photographic studio is just wack. That's fucking doo-doo to me. That's bullshit. What the fuck are you doing? The culture is so rich and so much of it comes from the street and from the hood. Why the fuck would you want to take someone out of the hood to take their picture?

"The culture is so rich and so much of it comes from the street. Why the fuck would you want to take someone out of the hood to take their picture?"

I imagine most photographers didn't want to go out to Hollis. Well, you know what? You're not doing the fucking artist justice, so fuck you.

The way that we share media, music, and art is really different from when you started taking photos. How do you think youth culture has changed in that respect? You see kids skateboarding now, and some kids don't even want to ride unless there's someone taking their picture or filming them. If they make the trick, they want it on film. We used to just do it for ourselves. I used to go out curb-grinding when I had teenage angst to make sparks on the curb with my trucks, to get out angst and to push myself. There was no one else around, it didn't matter. In fact, I was driven harder because no one was around and no one would see it… We had this great advantage back then of not having the media that we have now. That incubation period of being able to do things alone without anybody else watching you. You didn't even have the ability to share things on the internet. You didn't have the ability to have people see you around the world. In some ways, it's great that you can, but in other ways it doesn't let these things develop.

You have essays in the new book from Rick Rubin, Ad-Rock, Shepard Fairey and a lot of other notable figures. How did you go about getting them to contribute and how do you think the text complements the photos? Well, I asked everybody a few multi-layered questions. I wanted people to discuss their inspiration up to the time and at the time of the photographs that I'd taken of them. Everyone's got their own trail, and I was hoping to show that trail to inspire younger people and older people to continue the rebellious spirit. Now, certainly some people aren't as rebellious as they were at that time, but you could see the passion… These guys are all fucking masters. They all really gave a shit. And they worked fucking hard at what they did. They really cared. And it wasn't about becoming famous, as we all know, it was because it was something they loved.

To me, the standout is a passage by [Black Flag's] Henry Rollins. He ends it by writing, "Things were very intense but the real thing is always intense. The world blinked. We did not." Henry Rollins, in his old age, has become a phenomenal writer. He is a fucking pro, and I love him for that. He has honed his craft, because he could not write like that when he was in Black Flag. He has come to articulate things in a way… That little 200 words that he wrote is a fucking sledgehammer to a needle. He fucking nailed it.

The book ends with an essay from Gary Harris, who writes, "These players were not in it for the shine, they did it because they could. Their ethos was art for art's sake." What's the importance of following that ethos? How important is that? More important than anything else in life. How's that? People need to have confidence in expressing themselves in all forms of their life. Informed, creative, intellectual expressing of yourself and your ideas and your opinions is essential to moving the planet forward.

What are your rules? Live with integrity. That's my rules.

Glen E. Friedman's My Rules is out September 16 via Rizzoli. He's hosting a book launch at Brooklyn's Powerhouse Arena on September 23. More info here.