Photography by Irina Rozovsky and Diwang Valdez

Additional reporting by Neil Martinez-Belkin

Diwang Valdez

Diwang Valdez

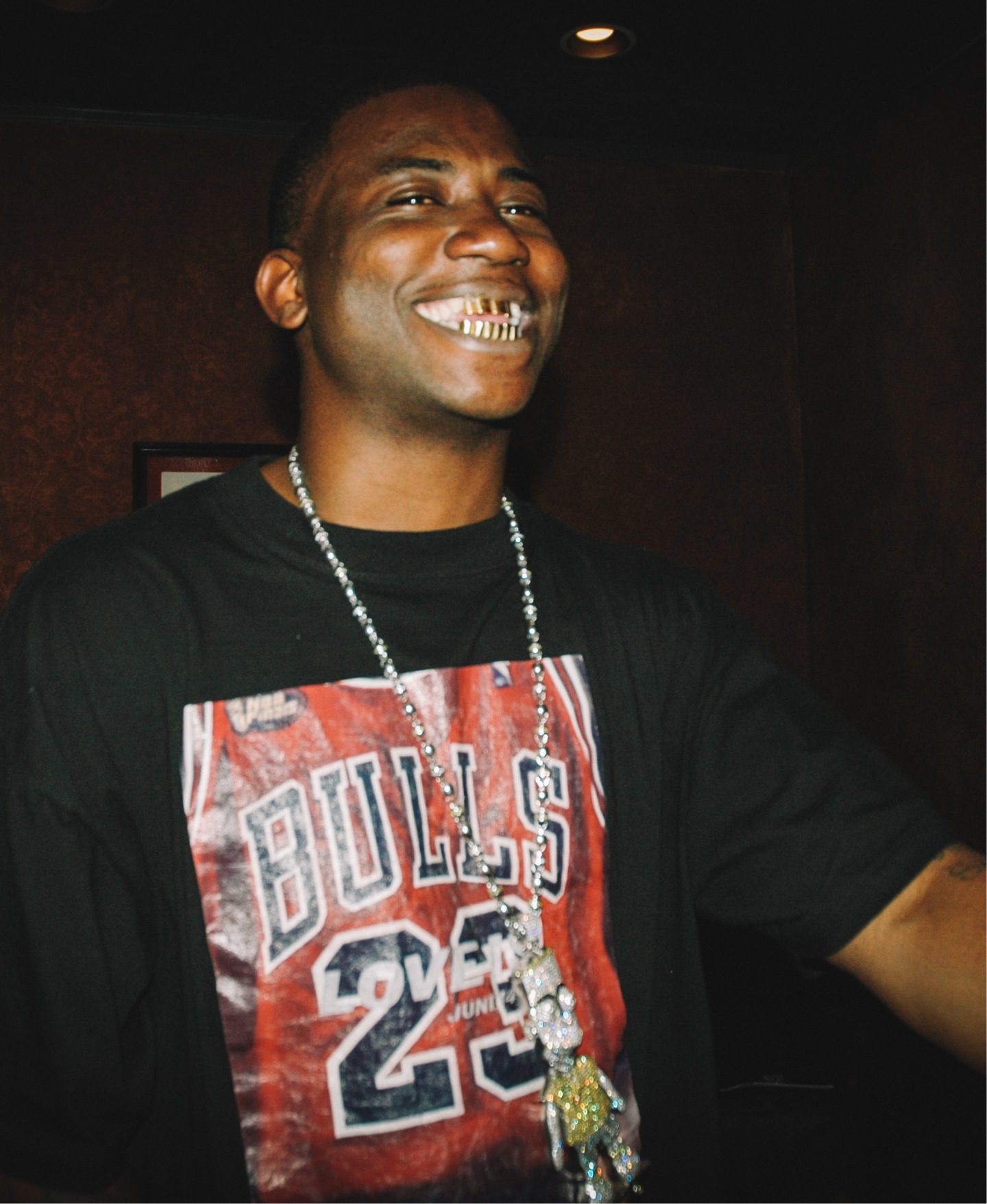

Love him or hate him, one thing’s for damn sure: there’s no denying Gucci Mane. Born in the outskirts of Birmingham but made in the streets of Atlanta, the marble-mouthed MC with the snot-nosed flow has spent the better part of the past 15 years overcoming just about every obstacle thrown his way—including many of his own making. His realness is of fantasy proportions. He has released more mixtapes than anybody, got in more trouble with the law than anybody, spun off more protégés, recorded more regional hits.

When I first caught up with him for a 15-minute phone interview in the spring of 2009, Gucci was fresh out of Fulton County Jail and riding a wave of excitement into what would prove to be the best summer of his career. A year or so later, I went to Los Angeles to shadow him during BET Awards weekend for a feature slated to run in SPIN. Those days were strange—Gucci spent a lot of time standing around the lobby of the W Hotel in West Hollywood, surveying the scene and not saying much. Late one night, he invited me to join him and a young woman he’d just met for an intimate conversation at a small lounge table that felt better suited for two. We hustled in and out of a Hollywood nightclub with Suge Knight and hit the studio with Pharrell. Gucci visited the BET Awards gifting suites, but skipped the actual award show, hanging with the folks in the lobby instead.

I remember being struck by how closed off and guarded he was generally, and how dramatically he came to life when we were in the studio and there was music to be made. In L.A., our proper interview never materialized. Later, when we finally talked over the phone, the conversation was brief. Gucci dodged or shut down anything too personal; he abruptly ended the call when I started fishing, looking for anything to open him up. In the days that followed, he failed to show up to the photo shoot for the story, which SPIN ultimately scrapped for the print edition and published online instead.

When his next album failed to connect and news came that he’d been arrested again, I figured that was it. I thought he’d blown all of his shots and wasn’t destined to be one of the greats—that the Gucci Mane era was done. I should have known better. He hadn’t accepted defeat before, so why would he then? In fact, Gucci’s whole career refutes the idea that artists are either winners or losers. The lane he carved was all his own, and wide enough not just for himself, but a slew of other MCs, DJs, and producers in what would grow to be one of music’s most electric and enduring scenes.

Since, Gucci has continued to release music at an astonishing clip. His story has become a saga, touching artists and executives across generations and fans around the world. Yet even as his life has played out in public, much about Gucci Mane has remained a mystery, clouded by speculation and myth. In the following pages, 20 of his collaborators tell their stories, together drawing a portrait of a complicated man with a strong creative drive who has a good shot of being remembered as the hardest working MC since Tupac and the best A&R in Atlanta, if not the best A&R that hip-hop has ever seen. Spanning more than a decade, even this is an incomplete picture: emails to several key players went unanswered, and still more declined to talk. Gucci Mane also chose not to participate.

Today, he sits in the United States Penitentiary, in Terre Haute, Indiana, two years into a three-year sentence for possession of a firearm by a convicted felon. According to the Atlanta Journal Constitution, speaking from the bench at the sentencing hearing, U.S. District Judge Steve Jones told Gucci Mane, then 34, “You’re a young man. You have a full life ahead of you… [but if you continue to break the law] you’re going to wake up one morning broke. You’re going to wake up one morning back to prison.” Judge Jones then reportedly added, “I don’t mean any disrespect, but according to young people, my nieces and nephews, you are quite cool.”

Gucci Mane is born Radric Davis on February 12, 1980, in Bessemer, Alabama, a former coal town turned southwest Birmingham suburb. In the fourth grade, he moves to East Atlanta with his mom and older brother.

OJ Da Juiceman (rapper): [Our relationship] dates back to maybe late ’80s, early ’90s. We was living right across the avenue [from him] in [some] East Atlanta apartments called Mountain Park. This is back around the time when Nintendo cartridges was out. We became friends, trading Nintendo cartridges. We moved up the street, to the Sun Valley apartments on Bouldercrest. I think it was ’94, ’95. We used to go around to apartments and knock on the door and ask if we can take the trash out and whatnot to get us a dollar. You know how apartments have generators, like with a little green box on them? I remember sitting on the generator eating snacks, just beating on the generator. We called it “the green machine.” We used to beat on the green machine and we both started freestyling, rapping, thinking we had talent. We were just talking about a bunch of miscellaneous stuff.

Zaytoven (producer): Me and Gucci met in my mother’s basement. Maybe 2000, 2001. At the time I was going to barber college because I wanted to cut hair. I had a studio in my mom and dad’s house, so me and a couple of guys were going to record after class or whatever. Gucci was a friend of my buddy, and [my buddy] brought him there. Gucci wasn’t really that into music, but he had a nephew that he was trying to help get into music. He was going to pay me to make a beat for his nephew. The song was called “Lil Buddy.” So I made the beat for his little nephew and Gucci was rapping, teaching him how to do the song. I don’t know what it was, but I felt something special about Gucci at the time—the way he was helping his nephew out. We exchanged numbers, and then it turned into Gucci coming over to rap rather than his nephew. That’s how we got started. We were doing it for the fun of it. We were enjoying making beats. I thought he was a dope writer. He was so simple with saying all the right things and putting all the right words together. It became a working relationship from there. Me and Gucci had a chemistry. Wherever he went or whoever he teamed up with, I was rocking with him.

Ashford East Village apartments, formerly called Sun Valley, where Gucci Mane and OJ Da Juiceman started rapping together in the ’90s.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

Ashford East Village apartments, formerly called Sun Valley, where Gucci Mane and OJ Da Juiceman started rapping together in the ’90s.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

Burn One (DJ and producer): [In 2004] the Dem Franchize Boyz “White Tee” record was out, and there was a group that had [done a song] called “Black Tee,” like the response record. I called up the record label [that released “Black Tee”], so I could go by there and check out some music. I showed up and [Gucci Mane] was the only guy there. There’s like nine people on the original song—he was the only one that showed up.

Kevin “Coach K” Lee (co-founder of Quality Control Music, manager of Gucci Mane from 2009-2013, former manager of Young Jeezy): I met Gooch early, man. I was looking for him. He had this record called “Fork in the Pot,” and that shit was jamming, so I put it out there that I was looking for him. One day I was walking in Walter’s, this famous sneaker store in Atlanta, and he walked up on me and was like, “Yo, I’m Gucci Mane. I’m who you’ve been looking for.” About a week later, we were in the studio cutting “Icy.”

Zaytoven: I was at the barbershop and Gucci called me, like, “Hey, man, Young Jeezy wants to do a song with us.” I didn’t really know who Young Jeezy was, but I’m like, “Cool, I’m gonna leave the barbershop, I’m gonna make a beat, and we’ll go down there and do it.” Everything we did was coming from scratch, right off the muscle. We didn’t have stuff already pre-prepared or none of that. Gucci was just like, “I got the hook I want you to make the beat around.” He sung the hook, I made the beat, and we went down [to Patchwerk Studios].

Kori Anders (engineer): I was an intern [at Patchwerk], sitting in on that Jeezy session [for “Icy”]. Back then, Gucci was this happy-go-lucky kid that was just happy to have his foot in the door at a studio. Gucci and Jeezy were both on the come-up. I know a lot of other cities, every studio session is pretty isolated, people don’t really intermingle. But in Atlanta, everyone kinda knew everyone. It’s just a big melting pot.

Zaytoven: I was from California, so all of these other guys are new to me. That [session] was my first time meeting them. Gucci was bragging on me the whole time like, “Yeah, this is Zaytoven, he the best at this, he do this and that!” He’s putting it on real thick. I’m from the Bay Area so my music sounds a little different. But to Gucci, everything I did was the world. He loved everything I did. But when he played the song [for Jeezy and his guys], wasn’t nobody really feeling it. So Gucci was like, “Alright, Zay, pull up another one.” But I’m almost mad. I’m stubborn, like, “Well, nah, I ain’t about to pull up no other beat. This is the song that you done did all this bragging about.” Jeezy was saying he wanted to do something a little bit more street, but this is what we came up with. Me and Gucci do our stuff, it’s got flavor to it. It’s fun. It’s still hardcore music, it just has a frillier melody. It has a little brightness.

Coach K: They start working on another record. But Gucci kept singing this damn hook. He was singing the hook to everybody. Eventually, I pull Jeezy, and I’m like, “Yo, man, this shit may be kinda dope. It’s got a melody. He keeps singing the shit. We need to go ahead and cut this record.” So they went in and cut the record.

Zaytoven: Before you know it, it’s like everybody in the whole studio, people that ain’t got nothing to do with the song, they had a pen trying to write a verse to it. Lil’ Will was in there, Gucci had him sing the chorus for us.

Burn One: Gucci played me “Icy” a couple of months before it came out [in 2005], and I hated it because of the Auto-Tune on Lil’ Will. Gucci was so excited he put Auto-Tune on Lil’ Will from the Dungeon Family, but to me that was like blasphemy. I’m like, “How could you do that to him?” Three months later, it blew up.

Zaytoven: [“Icy”] was perfect. You’ve got Young Jeezy, the hottest guy in the streets. Then you’ve got Gucci Mane, who’s like an underground guy who’s trying to get on. Both of these guys need the song real bad. Jeezy didn’t even want the song, but he needed it. He had the streets on lock, he just didn’t have a song that defined “Jeezy got the hottest song out,” or, “Have you heard the new guy, Jeezy, on the radio?” He didn’t have one of them. So “Icy” was that. And for a guy like Gucci Mane, it was like, “This is my only shot. This is my only shot in the game so I’m not fixing to give this up to nobody.” “Icy” sounded like a Jeezy single because he’s rapping on the first verse, talking about jewelry—and him and the people he was with was always in the fancy cars, with all the jewelry, popping all the bottles—so it almost fit him. It just wasn’t his song. It was Gucci Mane’s song. So it started turning sour real quick.

Walter’s Clothing, where longtime manager Kevin “Coach K” Lee met Gucci Mane for the first time.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

Walter’s Clothing, where longtime manager Kevin “Coach K” Lee met Gucci Mane for the first time.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

Greg Street (DJ, radio personality, and early Gucci Mane manager): When the beef came about with Gucci and Jeezy, I stepped away. I didn’t want to be a part of that. [Jeezy’s label] Def Jam was trying to convince Jeezy to see if he could get [“Icy”]. Def Jam wanted the record to launch Jeezy’s career. But at the time, Gucci’s whole thing was, “Jeezy’s trying to take my record.” I was trying to make Gucci understand that it can be beneficial to you, too, in some circumstances, to let the signed person have the record. Because it’s still going to be your record regardless of who puts it out! And if it happens—if it blows up—sky’s the limit for what you can ask for in a deal. But he didn’t really understand that as a new artist. That’s how the whole beef started.

Zaytoven: I had never had a hit record before. I had never had a song on the radio. I’d never had a song played in the club before, really. So when I was going out to 112 or Velvet Room, and the DJ would cut the music off and everybody was singing the lyrics to “Icy,” I was like, “Wait a minute.” I can’t even really describe the feeling. It was everybody’s favorite song, it was the song of the summer. Gucci knew, “If I hold this song for myself, everybody know this Gucci’s song. I got the hottest song of the year.” By the time it made it to radio, I didn’t even want to hear it no more.

Greg Street: It never really should have turned into a beef. It could have been from the start a beautiful situation for both parties—and it did turn into a beautiful situation for both parties anyway because the record is a classic. But it also just escalated and never turned back. Most of these beefs in hip-hop could be solved with two grown men sitting down and having a conversation.

DJ Drama (DJ, radio personality, and founder of the Gangsta Grillz mixtape series): Me and Gucci probably met sometime after he did “Black Tee.” During that era, we were cool. When him and Jeezy fell out, it put me in a tough spot for us to work together.

Todd Moscowitz (co-founder of 300 Entertainment and veteran music executive, who signed Gucci Mane while president of Asylum Records in 2007): After “Black Tee” and “Icy,” Gucci came up to New York with Jacob York and we had a meeting. I had a pretty big office. I was sitting at my desk, and Gucci chose the chair that was the farthest away. I just remember him sitting there with these giant sunglasses on, and I don’t remember him taking them off. He said very little and he listened a lot and he didn’t give up anything. I was basically begging him to sign with us. I was giving him a very hard pitch because I was such a huge fan and I was so passionate about it. His facial expression—I don’t think it changed once during the meeting. Then he left, and ended up signing with Big Cat right after that, and started working on Trap House.

Zaytoven: We were doing records that just ended up blowing up. Big Cat had relationships with how he do the radio and all of that, so he could help us in certain ways. That’s how Big Cat came into play.

On May 10, 2005, five men attack Gucci Mane while he visits a friend at her house in Decatur, Georgia. The men tie his friend up, pistol whip him and threaten to kill him. During the confrontation, Gucci somehow gets his hands on a gun, letting off several shots as the men retreat. Two days later, the body of Henry Clark III, an aspiring rapper from Macon, Georgia, is found dead. On May 19, just days before the release of his debut album, Trap House, Gucci Mane turns himself in to DeKalb County police to face murder charges in Clark’s death. On the day the album is released, he posts a $100,000 bond but returns to jail a few months later after pleading no contest to a separate assault charge stemming from an incident in which he beat a club promoter with a pool stick. While serving the six-month sentence for this assault, the charges are dropped in his murder case due to insufficient evidence. The terms of his probation in relation to that assault case will dog him for years to come.

Zaytoven: I was in California [at the time of the shooting]. I didn’t even really believe it. And then I seen him on Rap City, and I could tell it was something serious. I could just tell in his whole demeanor. When I got back it was like, “Damn, Gucci Mane’s sitting down for six months. He on a murder charge.” For real?

Drumma Boy (producer): When we are tested, we see what we’re made of. And when Gucci got in that situation where people tried to kill him, he had no choice but to defend himself, and he got charged with murder.

Greg Street: You gotta think, they ran up on him. He didn’t even have a gun. He was just at the girl’s house [and was] able to take the other guy’s gun. [But] I guess, when something like that happens, everyone wants to label you as being a “tough guy.”

OJ Da Juiceman: I was doing a prison term when Gucci dropped Trap House [on Big Cat, in May 2005]. My mom and my sister came and got me from the prison. My sister bought the CD for me and showed me Gucci had started rapping. I’m like, “Oooh, wow! My boy done made it!” From then on, I thought if he made it, I could try to make it too.

Zaytoven: Nobody else in Atlanta wanted to work with me because it’s like Gucci Mane is the bad guy now in the city. Don’t nobody rock with him because everybody likes Jeezy or T.I. They are all with each other, or friends. Me and Gucci are guys that just came out the basement. Gucci got a murder case. I don’t know what’s going to happen [with Gucci’s case], but I know we got a lot of music. So I was like, “Well, I’ll take our music and put it out.” I was trying to brand myself, so I put me and Gucci Mane’s pictures on the cover and started putting all our music out. And people started really rocking with it. That has been our formula ever since.

Burn One: When he came out [of jail, in January 2006], I saw him over at Zaytoven’s. I was like, “Let’s do a tape.” He was like, “Nah, I got to do this album with Big Cat.” Within a month and a half, their relationship had soured. So he hit me like, “Yo, I’m ready to go.” He had a bunch of music recorded. Sporadically, over a month, we did a bunch of sessions. One night we went to a strip club and then came back to my studio at like 3:00 a.m. and recorded until 7:00. I would pull up a beat—I’ve never seen this—and he would go from top to bottom. He would be in the booth, did not want me to play a beat before he went in there, and from top to bottom would freestyle the whole song. Five minutes, three minutes, however long the beat was played for. Then as soon as the beat went off, he was like, “Alright, pull up another one.” He did 10 songs like that, not messing up once. The coldest freestyles. Gucci would just go and go.

Kori Anders: His mind works extremely fast. It got to the point where it wasn’t uncommon for us to record six or seven songs in an evening. I guess he liked the speed at which I worked because I was able to keep a faster pace than what he was used to [from] other engineers.

Greg Street: He makes records like Tupac. He makes records like Cash Money. He lives in the studio. That’s all he do.

Diwang Valdez

Diwang Valdez

“I would wake up in the morning and get a call from the studio, like, ‘Gucci’s here, he’s ready to work.’ A producer would start playing a beat, and five seconds later he’d be like, ‘Stop. I’m ready to go in.’ Eight hours later, five songs completed. That was a typical day for years with Gucci. And the sessions would be crazy. There would be 30–40 people there, but his ability to focus and tune out all of the background noise was just amazing.” —Kori Anders

Kori Anders: I grew up an avid Pac fan, and I came up under Leslie Brathwaite, who’s been engineering [for years] and telling me stories about Pac and how his work ethic was relentless. When I got in with Gucci, I wasn’t the biggest fan of Gucci’s music, but I’m a huge fan of his work ethic. And I drew parallels to the way he worked to how I heard Pac worked back in the day. I would wake up in the morning and I’d get a call from Patchwerk, like, “Gucci’s here, he’s ready to work.” A producer would start playing a beat, and five seconds later he’d be like, “Stop. I’m ready to go in.” Eight hours later, five songs completed. That was a typical day for years with Gucci. And the sessions would be crazy. There would be 30-40 people there, but his ability to focus and tune out all of the background noise was just amazing to me.

Drumma Boy: The myths I’ve heard of Tupac, I think of Gucci instantly. I think Gucci would be rapping on the corner or on the block, entertaining the hood, whether he’s famous or not.

Mike WiLL Made-It (producer and founder of Eardrummer Records): We met when I was going down to Patchwerk with my boy who was working there at the time. He was like, “Man, Gucci’s upstairs recording,” and I’m like, “Damn, for real?” So I went upstairs and I ran into him in the hallway and I was like, “Hey, bro, I been making beats.” He took the beats and went into the lounge and was just in there freestyling on my beats. I was waiting outside the room and I heard him rapping through the wall. This is like 2005. He came out and was like, “Man, I fuck with these beats, bruh. Ain’t you the one that made the beats?” He was like, “Come listen to this shit right quick,” and he had wrote something to one of the beats and he was trying to buy it from me right there. I ain’t really know what to say because I was just selling beats for like $100 or $200 at the time. I don’t know how the business works with these rappers that’s on and shit. He had offered me $1,000 and I was like, “Man, holler at my people and shit.” He could tell I ain’t have any people. But he got my number and stayed up on me.

Burn One: [In 2006] Gucci put out “My Chain” and thought that was gonna be [a hit]. That didn’t work. At the time, he was ice cold. I vividly remember as soon as I got the CDs pressed up for [the October 2006 tape] Chicken Talk, we went to the Old National Flea Market, the discount mall. We pulled up and I left [Gucci] in the car and walked in with these CDs. I was trying to sell them to a guy in the store, and he was like, “Man, nobody is gonna buy these Gucci Mane CDs. Nobody care about him.” He was going on and on about how Gucci wasn’t going to come back. So I literally just walked right outside and I put the music on in my car. Gucci was there, and we just started talking to people in the parking lot, playing the album—just booming CDs out of the parking lot, selling, selling, selling, selling. Twenty minutes later the guy comes outside, like, “Man, let me get 40 of those.”

Zaytoven: People [started] really gravitating to him, like, “Oh, Gucci Mane is the truth.”

DJ Drama: He was creative, and he was so Southern, so country, so hood. I think he just touched people. In a parallel way from how Jeezy did, almost. As different as they are, they’re similar in the way they touched the hood so strong. Their words, their wordplay, the content, and the subject matter—it created something that was very entertaining and was also something that people could feel. Gucci had a lot of character and personality in his raps. He was a character and a personality on his own.

Greg Street: He had all these records that were crazy big. He had “Pillz,” he had “Trap House.” You go in the club, and you can hear the DJ actually play 10 Gucci Mane songs in the course of a night, and some of those songs, you might hear them twice.

DJ Drama: “Freaky Gurl,” “Trap House,” “Vette Pass By,” “Kitchen”—those are the records, still to this day. When I play those in the club, it goes crazy. [But] “Freaky Gurl,” that’s when Gucci Mane really started.

Zaytoven: I think we did “Freaky Gurl” the same day we did “Pillz.” We recorded like seven songs that day. Shawty Lo had come over [and] a few [other] guys came through, but they didn’t get on the song. And we just recording, ain’t thinking nothing of it. It’s just like, “Damn, that does sound good. What time you coming over tomorrow? Let’s go crazy tomorrow.”

Burn One: Gucci had like this childlike wonderment with his music. This enthusiasm and energy. Just giddy. When he would write a line that he thought was clever or something he would just start laughing, like a little kid if they just cracked a little joke or something, you know? He got off on his own stuff. Not in an egotistical way, but like, “Man, that was cool. Look at what I did with that right there,” or whatever. He was amused by himself. He would say stuff to get a rise out of himself and other people. I was inspired just seeing his inspiration in it.

Old National Flea Market, where Burn One sold Gucci Mane mixtapes in the parking lot.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

Old National Flea Market, where Burn One sold Gucci Mane mixtapes in the parking lot.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

Zaytoven: [We’re still] doing music, but now he really doing shows. He’s moving around. Now the majors want to sign him. He too hot. That’s when I think he did end up doing the situation with [Warner].

Todd Moscowitz: In 2007, we finally decided to get in business and signed a deal. I can’t remember exactly how it happened—he was having some issues with Big Cat. As I remember it, we ended up doing a deal to buy him out of Big Cat and sign him. We spent a lot of time working out the logistics of separating [from Big Cat] and working out something with Cat as well. The first meeting, [Gucci] gave up nothing, but when we linked up again, he was so much more real and open. I got to see who he was a little bit. He was incredibly bright, but also incredibly transparent about where he was at with things. If something bothered him, he would say it. If something made him feel a certain way, he would say it. He would put everything out on the table. That was not something you see a lot, truthfully, in rap music. Everybody’s very, “This is what I think people wanna hear,” and, “This is what I think people wanna think of me.” Gucci didn’t care—does not care—in any way how people look at him.

In 2006 Gucci Mane meets Debra Antney, a music industry vet from Queens, New York, and the founder of Mizay Entertainment. Big Cat had brought her in to help Gucci fulfill the 600 hours of community service required by the terms of his probation in the 2005 assault case. From 2007 to 2009, she is Gucci’s manager and business partner. Her son, who Gucci would nickname Waka Flocka Flame, would become one of Gucci’s closest friends and associates. Together, he and Gucci would form So Icey Entertainment as a subsidiary of Asylum Records. Years later, So Icey would fold into a new venture, 1017 Brick Squad Records, under Atlantic Records.

Todd Moscowitz: The first thing that happened was that things got bumpy between him and Cat. For the first six months [of the deal], managing through that process was a big part of what we spent our time on. [In 2007], I think Cat was releasing Trap-A-Thon at the same time we were releasing Back to the Trap House. There was a whole lot of energy around Cat trying to drop the album right on top of Gucci’s album. Cat was trying to put “Freaky Gurl” on his album and we were trying to put “Freaky Gurl” on ours. It was a big tug of war that eventually got resolved. The first album was not a smooth process. Between what we were trying to do and what [Cat] was trying to do, it just got really confusing. I think it took everybody kind of off their game a bit. Consequently, I think Back to the Trap House underperformed.

Zaytoven: To me, [Back to the Trap House] took the dirt off of everything. It took the edge off. It wasn’t recorded the same. It’s all high-end recording. It wasn’t what we created. Now, we’re trying to put a commercial album out. Now, we trying to be like the rest of the rappers in the game. I’m like, Well, dang, maybe this is going to [take us to] the next level, so I’m gonna play my part. But it didn’t touch me like I thought it should.

Todd Moscowitz: Gucci’s got a million thoughts and ideas on every aspect of what’s going on. He really was making the music on his own, and he’s the most prolific artist that I’ve ever worked with. He might be the most prolific artist that anybody’s ever worked with. The volume of music that he makes is hard to keep up with. I’ve been closely associated with him for probably 10 years now—and I can’t keep track. [So] he was making the music, but there was new music every day. He’d be like, “I got this other record. I got this other record. And I wanna do this. And I wanna do that.” Coming off that album, he basically went on a fucking spree of putting out mixtapes. It was a huge run.

DJ Holiday (DJ and radio personality on Atlanta’s Streetz 94.5): I was just a little, young DJ trying to find my way, looking for that next step to put myself in a better category where I could make real money off this and pay my bills. Gucci used to come [to Zaytoven’s mom’s house] every so often. I was like, “Yo, that’s Gucci Mane?” And [Zaytoven] was like, “Yeah, but he really don’t talk to people.” So I was like, “Well, I’m a fly on the wall. I ain’t gonna say nothing too much to him other than what I wanted to say.” Zaytoven was helping me develop my mixtape brand, giving me throwaways—songs that artists recorded at his studio and then didn’t use.

OJ Da Juiceman: Gucci asked if I could go on the road. I’m like, “Shit, boy, I can’t wait!” I’d never left Atlanta. I wanted to try some of this stuff too. He won’t say that I was his hype man, but I was his hype man. I knew every word because we were boys and I liked his music. So I would hype-man his music on the road, but at the same time I was pressing up my own CDs. I started taking 2,500 CDs to each show. Before he would perform, I would pass out some CDs [and then] save some so that when we got on stage, I could pass out more CDs. He’d seen the fact that I was going hard like he was, hyping him like his music was my own music. So he kept me on the road a little more.

Diwang Valdez

Diwang Valdez

“The jail stints slowed him down, but at the same time I think those were times where Gucci Mane got to rest and reevaluate everything and get back hungry. Gucci is built for this stuff. I hear guys rap about how tough they say they are—Gucci Mane one of them guys that’s that for real.” —Zaytoven

Zaytoven: OJ [and] all these young little other guys was coming up—Yung LA, and Yung Ralph, and other guys in the city like Gorilla Zoe. Those guys [were] ready for their shot. If [me and Gucci were] doing ten songs a day, Gucci ain’t gotta do every verse on every song. We’d get some different flavor from different people. So I’d use Gucci Mane as the big dog, like, “You all do some work with me, I’ll probably get Gucci to do a song with y’all.” Gucci Mane [would] come in and do some records with these guys and give them a stamp and it’s like, “Okay, OJ the next hot guy.” And I was surprised, like, “Dang, OJ on fire right now!” [“Make the Trap Say Aye”] wasn’t originally OJ’s song at first. He was just [going to be] featured on there.

OJ Da Juiceman: We made “Make the Trap Say Aye” in the studio at Zaytoven’s mother’s house. When I seen Gucci didn’t want the beat, I looked at Zay, tapped him like, “Put that to the side for me.” Once Gucci was done with his session, I asked Zay, “Can I record that song?” And Zay’s like, “Hell, yeah, you know it’s all good.” I had already had a hook—Quarter brick, half a brick…

Zaytoven: Later on, OJ came in like, “Aye, bruh, this my single right here.” And we’re like, “Alright, take the files and get it mixed.” But he ain’t even get it mixed. It was just playing the way it came out the basement. And it’s like, “Oh, dang, this song blowed up for real?”

OJ Da Juiceman: I’d say I worked on that song two and a half years before it blew up.

Zaytoven: That’s when my mama’s house started getting so full of everybody trying to buy beats. “Make the Trap Say Aye” really solidified me, as in, “Okay, it’s a certain sound that this producer has that don’t nobody else got.” That’s when my sound really started becoming what it is. The way that the drums are, and that dirty, kind of trappy sound—I feel like it’s the most mimicked sound in the rap industry even right now. I know for the South it is. I’m still making them same beats over and over again today, and people are still coming to buy them because they feel like “I’ve got to have this.”

Kori Anders: Seeing the amount of success that a lot of people around Gucci have, it’s almost like he saw things first. I recorded Yo Gotti before I even knew who he was. Gotti showed up and Gucci’s like, “He’s gonna go in and rap.” Gucci had a knack for knowing, “I see something in that guy and he’s going to be special.”

DJ Holiday: Every person I grew up with called me the day [my 2008 mixtape with Gucci Mane] EA Sportscenter dropped, like “Holy shit, dawg, you made it.” I was just happy the shit actually came out because up until the day I recorded myself talking shit over the tape, I still didn’t know if Gucci was gonna use it or not. It was a long, grueling process, but it worked out. The same store that wouldn’t take my CDs [before], motherfuckers [were] asking, “Can I get a print-up of two or three thousand copies?” I felt like, “Damn, this Gucci Mane dude really got my shit going crazy!” After that, it was the phenomenon of just dropping.

Todd Moscowitz: He put out Sportscenter and Gucci Sosa and Mr. Perfect and Bird Flu 2 and all this stuff. That went on for a year and change, to where I wasn’t sure when I was getting an album. He just kept putting music out.

Kori Anders: He picked that up from Lil Wayne. He’d look at Wayne when [Wayne] went on that whole rampage of dropping tape after tape after tape, and he saw the success he was having. I remember him saying, “I can do that. I can record as much as Wayne. I can put out just as much music as him.”

Mike WiLL Made-It: We fell out of contact [after that first meeting at Patchwerk], and then me and Waka [Flocka Flame] met each other on another note. So Waka put me on the phone with Gucci, and we kind of clicked. I had just gotten out of high school. I’d take my mom’s car, drop her off at work in the morning, and use her car to go to the studio to be with Gucci all day. We did [the November 2007 mixtape] No Pad, No Pencil—he rapped on 20 beats in three days, all freestyles.

Drumma Boy: It’s a lot of positives behind working with Gucci and a few cons. Having so much music leaked and put out for free, that’s the downfall. He’s getting paid on shows, performing all over the world off of a mixtape you just dropped, but unfortunately [for] the producer, nobody eats. It’s more of a reputation thing [that helps you with] attracting other clients.

Todd Moscowitz: I wanted an album, obviously, but I think we figured out what eventually became the new way to market. I wasn’t being overly precious about the fact that he was putting out free music.

DJ Holiday: “Bricks” [from 2008’s EA Sportscenter] really took the fuck off. DJs in different cities were calling me, sending me videos of them playing the record in the club and the whole club going crazy.

Mr. Boomtown (director): At this time, I was living in Dallas. I wasn’t really a big director. A friend of mine was a dancer in ATL—she was cool with Gucci. She called me with him on the phone, and he made it seem like he already knew who I was. I sent him to my MySpace page to check out some of my videos. He hit me back, and we went [to Atlanta] to meet him, but once we got out there we couldn’t get in contact with him. We finally got in contact with Deb Antney, Waka’s mom, and she invited us over to their crib. They all pretty much lived together. She cooked for us and we shot the breeze, just talked business and videos. By the end of the day, Gucci finally showed up. They cut us a check for like $40,000—keep in mind, they had just met us—and it was supposed to be for two videos. We winded up shooting like, three, four months later—I held on to that money all that time. “Bricks” was our first video with Gucci Mane. We had Nicki [Minaj] in the video; we had Waka, Yo Gotti, DJ Drama. I think we had Yung Ralph.

On January 16, 2007, Atlanta police raid the offices of DJ Drama’s Aphilliates Music Group, arresting Drama and his partner Don Cannon, as well as 17 others, and seizing over 50,000 mixtapes. Conducted as part of the Recording Industry Association of America crackdown on bootlegging, the raid shakes the mixtape game to its core and causes the artists and labels who work with Drama to produce promotional mixtapes to cry foul.

DJ Drama: [Gucci Mane’s September 2008 mixtape] The Movie was one of the initial tapes that happened after the raid. The mixtape game was in a different space, and I remember feeling The Movie didn’t have the big impact I thought it would have. I wasn’t printing up a lot of CDs, so the tapes just started to float through the internet. You couldn’t really feel who’s getting it or how they’re getting it. But over the next four, five, six months, I realized as I would travel that the tape had started growing. “Photoshoot” hit the clubs and stuck. When I look back, that’s a tape that people consider one of the Gangsta Grillz classics. Gucci wound up getting locked up not too long after we released it.

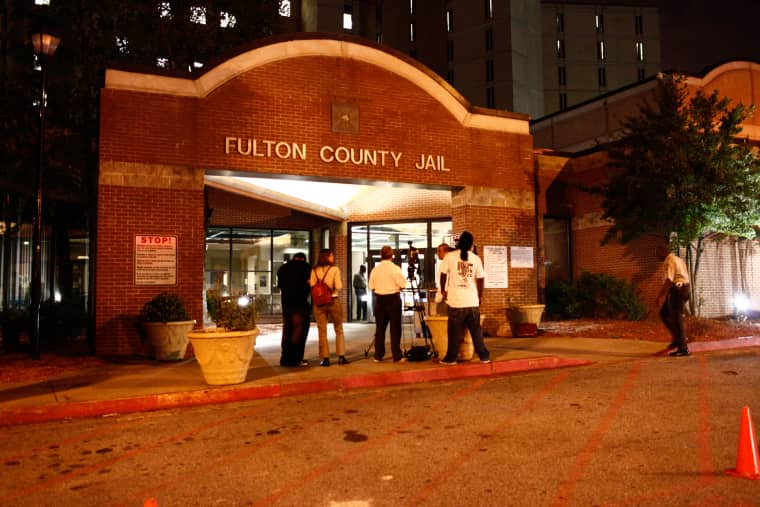

On September 12, 2008, Gucci Mane receives a sentence of one year in jail for failing to complete his 600 hours of community service. (He had only completed 25 hours at the time.) He serves six months at Fulton County Jail and is released on March 13, 2009.

OJ Da Juiceman: When I heard [that Gucci had gone back to jail], I’m like, “I gotta keep the flame on so people won’t forget him.” At all my shows, I’d always do a Gucci set. I’ll tell you, they were hype! Boy, them folks were going crazy. When Gucci came home [in March 2009], it was a burst of videos [and] back to the Atlanta nightlife. We were going to every club. We did so many videos—even songs I wasn’t on, I was right alongside him.

DJ Holiday: The day he got out of jail, he came to the studio and recorded “First Day Out.” If you’re a Gucci fan, that’s a hood classic anthem. If there would ever be a movie about Gucci, that would be a dope-ass scene—the whole fucking room lit up when he did that verse: I start out my day with a blunt of purp…

Todd Moscowitz: He got out and it was all sorts of madness. He was going in so many different directions. He was doing a million shows, people had booked him in one city while he was away somewhere else. In every city, there were like three promoters that wanted the show.

Coach K: Me and Jeezy, we split in 2007. In 2008-2009, Gucci started to get really, really hot. I mean, he’s got the streets fucked up. I happen to run into him at Patchwerk Studios. He came up to me, like, “Yo, I really never had no problems with you. Me and Jeezy didn’t see eye-to-eye, but I never really have no problems with you.” We ended up exchanging numbers and talking and shit, and at the time he was signed to Warner Bros. Todd Moscowitz was running Asylum/Warner, and Todd brought me on as a consultant to help put Gucci’s album together. During that time, Gucci and I spent a lot of time together. I started managing him after that.

Lex Luger (producer): I signed [with Brick Squad Monopoly] in 2009, when I turned 18. Me and Waka were renting out Gucci’s old house—didn’t buy no furniture, just bought studio equipment. At one point Gucci was staying with us [and] all of us was there working 24/7. He and Zaytoven redid the whole basement and made [a studio] right beside his bedroom. So when Gucci got up in the morning, he didn’t go to the bathroom—he went to the studio. That’s why he said [in “First Day Out”]: No pancakes, just a cup of syrup. Like, “I don’t want nothing to eat. I’m waking up and I have to work.”

Todd Moscowitz: Gucci was the director of the movie, and I was the producer. He was running down the field, [and] I was running alongside him trying to figure out what to do. This kept going on until he eventually hit “Wasted.” When that happened we all knew what to do.

Fatboi (producer): The first thing he said when he showed up to the studio was, “What do you think about doing a song called ‘Wasted’?” The idea was: What if we can take this suburban term for getting fucked up and flip it and make it urban? Then maybe it’ll bounce off urban back into suburbia, because they already think everything that’s urban is cool. Now that could be huge. He was thinking about the [May 2009] Writing on the Wall mixtape, but I was already thinking, this is going to be the song that kicks his album off.

DJ Holiday: I was leaving the radio station—I was an intern at Hot 107.9—and Gucci randomly called me and asked me to pull up on him to hear some shit. I came to the East Side somewhere on Bouldercrest, he was at a house shooting dice or some shit. And he said, “This the one that going to take me out the hood.” That nigga was right.

Fatboi: When he left—and to this day Gucci probably doesn’t know this—I worked on that record for like a week straight to get it to be the song that it became.

Todd Moscowitz: We realized that there’s a change going on with radio. Street records are actually radio records, and we shouldn’t fight that. That’s a good thing for us. “Wasted” was a record that was one of those street records that sounded like it had much bigger potential.

Zaytoven's current home studio.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

Zaytoven's current home studio.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

DJ Holiday: Gucci was already was hood rich, but “Wasted” took us to doing MySpace parties in Orange County, doing Bar Mitzvahs for like 75 grand and shit. Them white kids and they dads, they topped off for Guwop to come perform that one song. It wasn’t just hood shit no more. We did the ESPYs and performed at the ESPY party [in 2010]. “Wasted” was always the go-to record. It was bigger than life. [In Atlanta,] Birthday Bash is like Summer Jam [Hot 97’s annual New York concert]. As a kid, you and your homies save enough money to go, sit way up in the nosebleeds. Then here I am on the fucking stage, about to DJ for the biggest artist on the bill. It’s a weird feeling, to know that your dude is about to headline Birthday Bash.

Zaytoven: Gucci being in jail [had] just helped him that much more because people just waiting on him. The whole Birthday Bash crowd, all they waiting on is Gucci Mane. Me and OJ were on stage before Gucci come out, and they cut all the lights out for a long time. It was like, “Dang, is he even coming out?” Then he came out, and they did “Make the Trap Say Aye,” and it just erupted the whole place. He did his whole show with “Bricks,” “I’m a Dog” and all the street classics. It was like, okay, can’t nobody beat him right now.

DJ Holiday: He brought out Nicki because she was on Writing on the Wall. He brought out Waka, Frenchie, Wooh, all of them. That’s when the whole 1017 movement kicked the fuck off in the city.

Coach K: He was hot as hell. He had like five records going at the club: “Wasted,” “Bricks,” “I Think I Love Her,” “Photoshoot,” and “Set It Off”; “She Got a Friend” with Juelz [Santana] and Big Boi. From the hood clubs to the Hollywood clubs to the hipster clubs—all of ’em was playing the same shit.

Todd Moscowitz: Then all of the remixes [featuring Gucci] came out: the Mario, The Black Eyed Peas, the Mariah Carey. Every street record had him on it.

Kori Anders: People were calling my phone to get at him. Talib Kweli called me directly [to get to Gucci].

DJ Drama: We were on a roll. He came to me with the title of the [October 2009 mixtape] Burrrprint, and I was like, “That’s fucking genius.” It was around the time of the [BET] Hip-Hop Awards, and that tape was just one of the ones—like the way Trap or Die was, or the way Future’s wave is right now. Gucci was hot as fish grease, and Burrrprint was going like hot cakes. I remember the attention it was getting, from the streets and from the critics alike. Gucci had surpassed just being a street rapper and everybody was on his dick.

Todd Moscowitz: We were moving towards putting an album out in the fall [of 2009]. Then a month before the album, he was like, “I wanna put out three mixtapes.” We were like, “We just went on this whole mixtape run. It’s time for the album.” He’s like, “No, trust me, I got this.” So he dropped the Cold War series.

Coach K: Todd was trippin.

DJ Holiday: [That was] one of Gucci’s random ideas. He’s just creatively always thinking about new stuff to do and what can he do to one-up on somebody. He was always like, “They sleep, bruh. They sleepin; I’m working. That’s how we gonna kill ’em.” And that’s what we did.

DJ Drama: Gucci was such a workhorse, he really only let Burrrprint live for like two weeks. You go and drop this instant classic tape and then two weeks later, here comes three more. That idea was dope, but I wasn’t all the way with it. I was like, “My nigga, let’s let it breathe.”

Kori Anders: He felt weird not recording. He felt weird sitting on records. When he recorded a record, he wanted to put that joint out that night. And sometimes he did that. He would record in the morning and by that night it was on the radio or played in the strip club.

Coach K: You’re not going to outwork him. Period. To finish up [2009 album The State vs. Radric Davis], we shot six videos in two days because we knew he had to go [back] to court and we didn’t know if they were going to keep him or not.

Mr. Boomtown: We would shoot what I would call marathons. That’s when we did “Heavy,” “I Think I Want Her,” “Bingo” with Soulja Boy and Waka. From the set, they’re either going to the studio or to a show.

Coach K: At the time, he was in a rehab program, and he used to sneak out and come to the studio and we would knock out records.

Todd Moscowitz: He was basically ready to hand the album in, and it was amazing. It had “Wasted” on it. It had “Lemonade.” It had a lot of great, great stuff. In the middle of this whole process, Gucci gets sentenced to go back to jail.

Coach K: Everything was going, all cylinders were open. Then he had to sit out for eight months. Most of the records were done, but I had to go in and put an album together while he was in jail. We didn’t even get to promote the album or anything.

Todd Moscowitz: Among the good things we did, we started opening up the alternative audience a little bit. One of my best friends, Kevin Kusatsu, is partners with Diplo. He was like, “Oh my God. Diplo’s a huge Gucci fan.” We got Diplo to remix the Cold War series and pull a couple of records from each tape and basically put his own version out.

Coach K: Diplo sets, they play electronic music, but those hipster kids, they want to hear that real deal trap shit. And Gooch was the king of that. Diplo and them play the world. Electronic music is huge. So if we can take Gucci’s vocals and put it on some hard-hitting electronic beats and service the world with that shit? That’s just going to make his fan base even crazier. So I picked out the a cappellas. When that tape came out it was huge.

DJ Holiday: One time we was in L.A. and Gucci was like, “Yo, you want to go to a techno party? This shit gonna be big one day.” I was just like, “Nigga, what do you know about a techno party?” He liked the lights, the beats, and all that type of shit. He was rapping verses to me in my ear to the techno beats. And I said, “Well, you know one day this shit might merge.” Now you got people like DJ Carnage who mix these trap beats with these EDM beats.

Todd Moscowitz: While all the jail stuff was going on, we got a huge buzz off the mixtapes, the white college kids were going crazy over “Wasted,” Diplo was remixing these records, and Diplo and Mad Decent put out that Free Gucci T-shirt, which became a meme and a huge viral sensation. All of those things were kind of happening at the same time. And then Gucci, before he goes away, delivers this “Lemonade” video—all yellow everything. It fucking popped the balloon at its highest point.

Coach K: Gucci used to tell [“Lemonade” producer] Bangladesh, “Give me that crazy shit [that] don’t nobody want to rap on! And I’m gonna go stupid retarded on it!” And then he went in there and we did “Lemonade.” Gucci freestyled a lot, but he also used to write. That was one of the first times that I seen him sit there and really write down the song.

Todd Moscowitz: “Lemonade” showed how musically diverse and ambidextrous he was. But the album itself was amazing. It came out. It sold 90,000 [copies] first week. It was a huge statement for him.

Coach K: Right when we got it to the place where it was like, “Damn, we’re about to crush these dudes,” we kept having setbacks.

DeKalb County Jail, where Gucci Mane was transferred after a 2013 arrest.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

DeKalb County Jail, where Gucci Mane was transferred after a 2013 arrest.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

On November 12, 2009, Gucci Mane returns to Fulton County Jail after receiving another 12-month sentence for violating the terms of his probation. He serves six months and is released on May 12, 2010.

Todd Moscowitz: The timing couldn’t [have been] worse. He was white hot. It was at the biggest moment of his career when we were about to turn that corner, and then it happened. It was a huge emotional letdown.

Zaytoven: Anytime he sit down, all we talking about is, “Oh, Zay, I want to do a record like this.” Or, “Check this out, I just wrote this. Make a beat for this.” It’s like he’s still out [and] right around the corner. So the [jail stints] slowed him down, but at the same time I think those were times where Gucci Mane got to rest and reevaluate everything and get back hungry. Gucci is built for this stuff. I hear guys rap about how tough they say they are—Gucci Mane one of them guys that’s that for real. He just as happy when he in there as he is when he out. And I’m right there in good spirits with him every time. If he didn’t [keep] getting put away the way he did, he wouldn’t come with the records like “First Day Out” or the street records that make him so relevant still to this day. [Those] come from him bumping his head over and over. There’s a certain edge that come with that.

DJ Holiday: He never brought his personal shit to the studio. That legal shit, that’s him and his lawyer. He wasn’t emotional, like, “Aw, I’m fucked up!” That nigga going to jail, he’ll call from jail, first day in there, like, “Hey, Holiday. Get my hard drive, put out some tapes. I’ll let you know when I want to drop them.” Cool. A lot of people was intimidated from the whole [2005] murder case situation. How many people you can actually say you stood next to that killed somebody? He defended himself, but this motherfucker really walked the walk and talked the talk of what he do. Nobody would try his ass. He was like the pied piper of the hood. Everybody wanted to be around him and absorb that energy. I walked with that man in the city of Chicago and you would have thought motherfucking Nelson Mandela showed up or some shit.

Coach K: For Gooch, when he goes and gets locked up, it hypes his fans up even more. [They’re] waiting on him. But you gotta build that shit back up. [So] I go in and I do a whole mixtape while he’s locked up—[March 2010’s] the Burrrprint 2.

Richie Abbott (former VP of urban publicity at Warner Bros. Records): It was the first mixtape that he put out that you couldn’t just get off of LiveMixtapes or DatPiff. There was a huge debate over that. I don’t even know that Gucci wanted that to be available only commercially. I think that was a decision made on the part of the label.

DJ Drama: They did the Burrrprint 2 through Asylum, with Holiday. Which at the time I was hot about because, you know, “What the fuck? This is a series we did together—how dare this not come to me?”

Coach K: The Burrrprint 2, we did over 100,000 [sales].

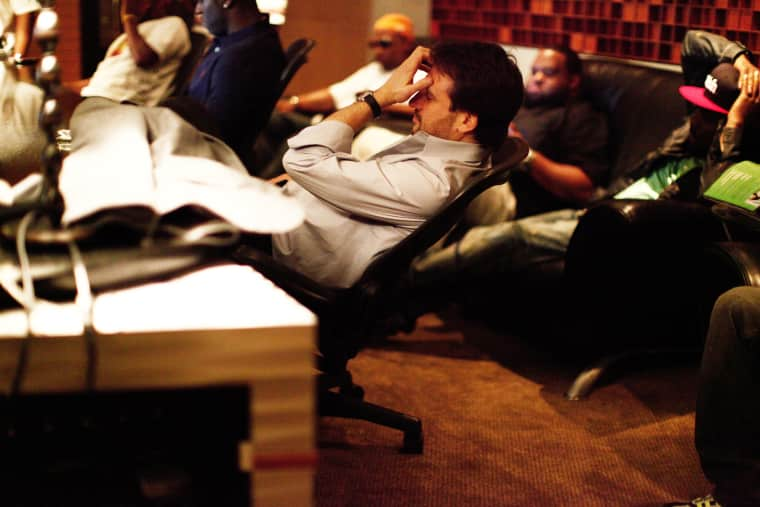

Todd Moscowitz: He got out in May [2010]. I went and picked him up at Fulton County Jail. Wale was somehow in the SUV with us and we all went straight to the studio—Gucci in one room, Waka in the other. That was the night Waka made “No Hands.”

Drumma Boy: Gucci booked the whole Patchwerk Studios. I gave him a folder of beats. The first song we did was “Abnormal.” He takes that beat, goes in the studio, and I go in the B Room and [there’s] like 100 people [in there]. The B Room in Patchwerk is not that big. I got all my equipment—my beat machine, my keyboard—everything lined up, but I can’t even touch the keyboard. So if you listen to “No Hands,” the chords are super simple because I’m barely able to play a damn chord. I’m reaching over people making the beat. And then I got back to the A Room, and we do “Ferrari Boyz.” I make beats off of my emotions, and that night I was just so relieved and so happy to see all of us together. It was almost like a family reunion—you and all of your favorite guys in one studio making history.

Todd Moscowitz: Obviously “No Hands” turned out to be a huge hit.

Richie Abbott: The State vs. Radric Davis was a great example of a mixtape artist kind of transitioning and kind of going mainstream. [But] I’ve seen this movie so many times, I don’t even want the DVD. Gucci just was not ready for the next level of success and what it took at that time. Anything that was really mainstream—like New York Times or late night television or maybe SPIN or Rolling Stone—he never really got up for it. He was just in his own world. I respect that, but it felt like he was maybe not totally in a good place to play the game.

Todd Moscowitz: He came out with the best intentions. I remember him saying, “Big dog, I got this.” He was focused. He was gonna get this done. And then he fell back into a bunch of trouble.

Kori Anders: He [went] from this happy-go-lucky guy that loved being in the studio into this darker space. I think that had to do with pressures the labels were putting on him.

Coach K: I think that sophomore album curse hit Gooch. Because although we had a great album, he wanted to go bigger and bigger. He was like, “Get me in the studio with Timbaland. Get me in the studio with Pharrell.” All these big names. No disrespect, they are incredible producers, but I think we started running away from everything that got us there. And his fans let us know that. He’s raw on everything he got on, don’t get me wrong, but I think The Appeal album, he was going through a lot. The court shit, that was on him bad, and I think he just wanted to kind of change people’s look on him.

Kori Anders: I think that pressure of trying to juggle keeping it real for the streets but also trying to get to that mainstream success was just at times too much for him.

Todd Moscowitz: Gucci was definitely struggling and spiraling. We were having a lot of trouble getting stuff done, and at the same time Waka’s stuff was really taking off.

Richie Abbott: That was the beginning of the fallout between Gucci and Waka. One guy is kind of falling off. He helped escort the other dude in, and the other dude is taking off. It’s kind of a classic scenario.

Todd Moscowitz: Waka was like, “I’m doing a mixtape.” He played the mixtape and we fought to get “No Hands.” There was an argument as to whose record it was, but it was our session, so we ended up with the record. Waka plays the rest of the music, and he’s like, “These are all street records. This is my mixtape.” We’re like, “That’s ridiculously good. That’s your album.” Street records were becoming radio records. and Waka started getting super hot over the summer. Gucci’s album [The Appeal: Georgia’s Most Wanted] came out in September. Right after that, everything kind of fell apart.

On November 2, 2010, Atlanta police discover Gucci Mane arguing with an unnamed man after driving his Hummer down the wrong side of Northside Drive. According to the Atlanta-Journal Constitution, the police use pepper spray to bring him into custody. They arrest him for traffic violations, damage to government property, and obstruction of justice. Although charges are later dropped “for want of prosecution,” the incident sends Gucci back to court for possibly violating the terms of his probation. On December 27, 2010, Gucci’s lawyers file a Special Plea of Mental Incompetency on Gucci’s behalf, saying that Gucci is “unable to go forward and/or intelligently participate in the probation revocation hearing.” On January 3, 2011, a judge in the Superior Court of Fulton County orders Gucci sent to Anchor Hospital, a local psychiatric and chemical dependency center. On January 13, 2011, days after his release from the hospital, photos began circulating online of Gucci’s new tattoo—a “Brrr” branded, three-scoop ice cream cone shooting lightning bolts on his right cheek.

Todd Moscowitz: I don’t want to get too into his personal stuff, but that [2010 arrest] was kind of the last straw for me. Each time, we would recommit to each other and work together. He would tell me he was going to be the biggest artist in the world, and this time it would be different. But we ended up in the same place, obviously, a couple of times. It had an impact on [our] relationship, honestly. I think he felt bad about it. I felt bad about it. It was really, really tough. Tough for him. Tough for us. Tough for me and him. We definitely had a bumpy time after that. There were a couple of months where we weren’t in as much contact, and then we reconnected.

Coach K: When he gets locked up that time, I went in and did another mixtape—The Return of Mr. Zone 6. I had to take it back to the streets. We figured out that Gucci fans need music, we have to supply them with music. He has a cult following.

Drumma Boy: Warner was down about Gucci getting locked up and not being able to do shows he had lined up. I was like, “What do you think about putting out a mixtape or an album that I executive produce? I have so many songs [by] Gucci. We can put something out on iTunes and make some money.” They okayed it, and Gucci called me from jail like, “It’s gonna be a lot of pressure on you, [but] if we can get it done, I’m down.” They sold 22,000 copies first week. For them to spend $150,000 on the budget and make $2.5 million within a seven-eight month period, that’s a hell of a turnaround.

Coach K: Even the label agreed after that. They were like, “You’re right. All that [chase for] Top 40, all that shit, don’t worry about that. Let’s just get his music out there to his following.” On Mr. Zone 6, we did 100,000 [sales], and that was a mixtape. After that, we set the trends. I went into Warner, where he had a label deal, restructured and negotiated a whole mixtape deal for three mixtapes for a certain amount of money outside of his album deal. It hadn’t been done. After we did that, you start seeing artists come out and put these mixtapes out commercially. Shit, Drake just did.

Todd Moscowitz: I think I was the first label to put out mixtapes commercially. I realized, not just from my experience with Gucci, but also with Dipset and Cam’Ron, that the mixtapes were the albums. The major labels in general were too caught up with the distinction between what’s a mixtape and what’s an album—especially with the internet, the kids were past that. Sometimes we would give them away, and sometimes we would sell them and we’d say it’s a mixtape, but fuck it. It’s 17 songs that you can love. Why wouldn’t you buy it?

Gucci Mane, Waka Flocka Flame, Todd Moscowitz, and friends

at Patchwerk Studios, on the night of Gucci Mane’s May 2010 release from Fulton County Jail.

Diwang Valdez

Gucci Mane, Waka Flocka Flame, Todd Moscowitz, and friends

at Patchwerk Studios, on the night of Gucci Mane’s May 2010 release from Fulton County Jail.

Diwang Valdez

On April 8, 2011, Gucci is charged with misdemeanor battery for allegedly pushing a woman out of his Hummer after she refused an offer of $150 to join him at a nearby hotel. In September 2011, Gucci pleads guilty to two counts of battery, two counts of reckless conduct, and one count of disorderly conduct in relation to the incident. He is sentenced to six months in Fulton County Jail and ordered to attend anger management classes. He is released early for good behavior on December 11, 2011, after serving three months.

Coach K: He was in and out. He had a couple more stints in jail, but we was running.

DJ Holiday: For [February 2012 tape] Trap Back, he randomly called me at five in the morning. He felt like he hadn’t done a really, really hardcore trap mixtape in a while. He’s like, “Yo, my nigga, we got to get the trap back.” I was like, “We lost the trap?” [He said] “Nah, nah, nah, not like that. We always got the trap. But let’s just do this tape for the trap. We want our trap back.” We really started from the bottom. He went back to the East Side. Mike WiLL, Zaytoven, and all them turnt the fuck up.

Mike WiLL Made-It: I’d been working with 2 Chainz, Future, Shawty Lo—just different people in the city, working on elevating my sound. By the time Gucci and I linked back up [in the summer of 2011], I had a new sound. We were in the studio and my phone rung, and my ringtone was Future’s “Ain’t No Way Around It.” He was like, “Damn, bruh, how I get a song like this?” I’m like, “Let me pick you a beat, and then you gotta go in and just do it with Auto-Tune, but do your version.” I gave him the “Nasty” beat and he was vibing. He was like, “I might put Wayne on this shit.” And I was like, “Wayne would be hard, but, shit, I think Future would be the look.” He knew who Future was, but I’m telling him, “That nigga Future hard as fuck. Put Future on that motherfucker, he gonna snap.” So Future got on that shit. And then Future got on the other song [I did] with Gucci with 2 Chainz, “Lost It.” From there Gucci [was] like, “Shit, I like Future. You think I should do a tape [July 2011’s Freebricks] with him?” I’m like, “Man, hell yeah.”

Todd Moscowitz: Whenever he got out—[December] 2011—we started talking again. At the end of the day, he and I are friends as much as we are anything else. As a friend, you just have to be there for people. When you sit down with a friend, you get past it. I’d moved from being at Asylum to becoming the CEO of Warner Bros. I moved out to L.A., and one day he came out to see me. He said again, “I’m getting my situation together. I’m gonna do this again.” I think I told him he should change his name to Trap God.

Coach K: We had a show out in L.A. This is one of the first shows Gucci did in L.A., a big concert party for The Hundreds. There were probably 3,000 kids in there. You got gangbangers, hipster kids, blacks, Mexicans, whites—it’s packed out. And when I say Gucci tears this place down, all you have to do is Google “Gucci Mane and Tyler, the Creator,” because Tyler got thrown off the stage that night by security. That was the first time Gucci was performing for all the little hipster kids. They were like, “Gucci’s God, man. He’s the god of the trap.” My wheels start running. And I start calling him the Trap God.

Todd Moscowitz: We came up with this idea and he started releasing these Trap God mixtapes. He wanted to put stuff out again, not commercially. I was like, “No problem. Do you. You won’t have any issues from Warner.” At some point I left Warner, but we remained friends.

Coach K: When they took the urban department away at Warner, [Gucci] had to go back to Atlantic, where the people he didn’t see eye-to-eye with were. They just didn’t get it. So we just started putting out our own music and releasing our own projects. [2012’s] Trap God was the first album that we put up ourselves on iTunes. We bucked the system. That’s when it got real. It created this frenzy again. The streets were back on fire. Future was already booming. [Young] Thug was running around. But when Gucci had the Brick Factory [studio], it was a home for all the street rappers. Gucci gives you that confidence. He makes you feel comfortable. You’d come over there, you can record, you gonna get records done. The Peewees and Thugs and Migos—[when] he invites you to the studio and he actually doing records with you, that’s big.

Sean Paine (engineer): Gucci requested me to record him one day when no other available engineers were around. I actually wasn’t supposed to be doing this shit, but I took a chance. At the time, I was damn near homeless, sleeping in my car. He approached me with a situation where I could come stay with him and run his studio. So I took another chance. It was right after Christmas 2012.

Zaytoven: I’m the one that went and got every last piece of studio equipment that was in the Brick Factory. [Gucci was] like, “I need a studio for this room. I need a studio for that room. I need a studio downstairs.” And I’m like, “Cool, I’m gonna go make it happen.” They was sleeping and staying over there, recording every day.

The Brick Factory.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

The Brick Factory.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

Sean Paine: The Brick Factory was right in the middle of East Atlanta. It was two floors, three studios. A couple of lounge rooms. A weight [and] boxing room. It was non-stop working. We had Gucci in one room. Thug in another room. Peewee in another room. [Then] Peewee might leave [and] Zay pull up. [Then] Drumma Boy pull up. C-Note in the other room. All rooms were always occupied. I opened the gate. I watched the cameras. I had the strap. Shit. Made sure everything was on point.

Coach K: An artist might be in there writing [and] Gucci [will] be like, “Just go in the booth, man. Let your emotions out. That’s your heart. Don’t be scared.” That was his whole shit he’d tell artists. “Don’t even worry about it. Just go in there.”

Young Dolph (rapper): When I got close to him, I really seen that he wasn’t no different from me. Even though he was a major artist, he still do his thing like he’s independent. One thing he told me that stuck with me was, “No matter what, just keep on doing music. Can’t nobody control it. Can’t nobody do nothing. You ain’t gotta do nothing but keep dropping music.” So that’s all I did, all the way up to this point.

Quavo (rapper, member of Migos): We was grinding, shooting the “Bando” video [and] the streets were going crazy. I guess Gucci saw [that] and was like, “Man, we gotta find these young niggas.” He called my boy, and our manager was like, “Where y’all at?” We pulled up to the Brick Factory and we talked to him that day, and from that day on, it was just love. We locked in. It wasn’t no business, like you need to sign something. It was just love. No paperwork. We were just working all night [and] all day. He’d wake me up like, “Quavo! Quavo! Let’s do this. Let’s record.” He’s a workaholic. He might do a whole mixtape that night. We’d go to sleep in the studio.

DJ Holiday: The Brick Factory was like a school. All these people under one roof, trying to figure it out. Gucci was just over there teaching.

Rich Homie Quan (rapper): I learned a lot from Gucci: always record, never stop. You can never have too many songs. Whenever he would call, I would just go, cause I knew we were going make something great. We looked up to him like a big brother.

Cam Kirk (photographer): I was surprised at how down to earth he was. I worked with a few artists prior to him and I never got that level of respect. He took the time to learn my name and to address me by name and not “cameraman.” It’s not a lot of politics with him. He’s just in it for the art of creating and helping other people out. He treated me like the biggest photographer in the world, and I was just really starting.

Mike WiLL, Metro Boomin, Young Thug, Migos, Rich Homie Quan—we all have a middle connection to Gucci Mane. He touched all of our careers at a very early stage. He’s changed a lot of lives. It’s like a large tree branch of people that have been influenced or in some way impacted by what he’s been able to create. When he gets out, there are going to be even more people he’s going to touch because he never has a problem reaching out and trusting people.

DJ Drama: Gucci has been one of the best A&Rs, clearly, to come out of Atlanta, and beyond that.

Drumma Boy: Gucci has an ear for talent and passion. He loves to give people a shot.

On September 7, 2013, Gucci Mane begins a three-day Twitter rant in which he levels shocking, often vulgar, accusations at wide swaths of the hip-hop community, including Waka Flocka Flame, Nicki Minaj, and OJ Da Juiceman. The tweets spark widespread confusion and Gucci claims that his account has been hacked. Later that month, he appears to apologize in another series of clear-eyed tweets. He admits to an addiction to prescription cough syrup, asks for forgiveness, and says he will seek treatment.

Zaytoven: I was with him at the studio before that happened. I could tell that he was anxious. He was ready to make some moves.

DJ Drama: Gucci is erratic. He’s had his problems with substance abuse at various times, and I think it got the best of him. And Twitter, it’s dangerous. In one instance you can do so much damage. At that time, I thought it was a possibility that he could have been hacked because he was going extremely far. I was taken aback by it. But that’s Gucci. He’s not one to play the political game. One thing you can never take from him, that nigga has always been one of the realest and has said how he feels, and he stands by what he says. He doesn’t hold his tongue.

Lex Luger: If it was him or was not him, he spoke his mind. When business doesn’t work out, those emotions come out.

Mr. Boomtown: The last time we [had] talked, we couldn’t agree on a budget. When I saw [the Twitter] shit I was like, “Wow. He is going off. Shit, he taking shots at everybody. I know he gonna take a shot at me.” He didn’t, but then I got a call. Gucci was like, “Boom, man, put the trailer [for the Mr. Boomtown-directed comedy The Spot, starring Gucci and Rocko] up on WorldStar.” I’m like, “Huh?” [He’s like] “Man, it’s my movie. Put the trailer up on WorldStar.” That was the last conversation we had. I don’t know what happened that day, but I think he was just venting and it came out the wrong way. I never talked to him about it. Wouldn’t probably even ask him about it.

Parking lot at the Burger King at the corner of Moreland and East Confederate Avenues, where Gucci Mane was arrested in September 2013.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

Parking lot at the Burger King at the corner of Moreland and East Confederate Avenues, where Gucci Mane was arrested in September 2013.

Irina Rozovsky for The FADER

Just after midnight on September 14, 2013, Gucci Mane is arrested near the intersection of Moreland and East Confederate Avenues by police responding to a call from a friend who had grown concerned by his erratic behavior. According to a police report, as more officers arrived on the scene, Gucci grows increasingly agitated, “yelling and cursing and threatening police,” at one point even telling responding officers that “he would shoot [them] up.” Gucci is searched and found to have “a clear plastic baggie containing suspected marijuana” and a loaded .40-caliber Glock handgun in his right jean pocket. An EMS team sedates him on the scene and takes him to Grady Hospital, where he is charged with disorderly conduct, felon in possession of a firearm, possession of a controlled substance, and carrying a concealed weapon without a license. He spends a night in Grady Hospital for psychiatric evaluation before being transferred to DeKalb County Jail.

On November 19, 2013, Gucci is indicted by a federal grand jury on two counts of possession of a firearm by a felon, stemming from that night on Moreland Ave. and also from an incident just two days earlier—September 12, 2013—in which police responded to a disturbance at the office of Gucci Mane’s attorney, Drew Findling, and found a loaded .45-caliber Taurus among Gucci Mane’s things. Gucci claimed that the gun belonged to his girlfriend, who was not on the scene, and no charges were filed at the time.

On December 3, 2013, Gucci Mane is arraigned in federal court on the two gun charges, carrying a maximum sentence of 10 years and up to a $250,000 fine each.

Sean Paine: [The Brick Factory] closed that day.

Mike WiLL Made-It: This time, I was like, “Damn, man. The jail might not play with his ass because he got a lot of charges pending.” It was just like, “Fuck.”

Sean Paine: When I first heard that they were talking about 40 years, I was just astonished. I think everybody was. I couldn’t believe it.

Coach K: Gucci was just in and out. I love him to death, for real. But it’s still a business. When you’re putting all of yourself into something and it keeps happening, you need to make a business decision, so we went our own ways [in early 2013].

OJ Da Juiceman: Gucci is a good person in the heart. With the drugs involved, I can’t tell you, because that detours a lot of people and intervenes a lot. Deep down inside, I know he’s a good nigga. I haven’t really spoken to him and I can’t really say where we are right now. But we’ve slept in cars together, you know what I’m saying? He’ll always be my boy. No matter what.

Sean Paine: I ended up not engineering for a minute [and] I was working a regular job at the mall. Then I get a call [from jail, and] Gucci’s like, “I need you to handle [releasing music] for me. I ain’t about to let this stop me.” From then on, we’ve been dropping shit to keep him relevant and give the streets what they want.

Drumma Boy: He grinded his ass off for those years that he was free to make as much music as possible and put himself in a situation where when he can keep putting out music until [he gets] out. That’s what we’re seeing right now.

Sean Paine: Maybe Gucci knew [he was going away] ahead of time. Maybe that’s why he was working so hard. But we never discussed getting locked up. Hell nah. We were discussing him getting off probation. He’d been on probation for so long [and] he was just about to get off. We were discussing celebrating that. And then all this bullshit.

Lex Luger: Everybody make mistakes, but he really influenced the sound and the culture in Atlanta. Music is a part of it, but the way he moves, his interviews, all of that also influenced people. Not just the music. As a black man, that’s an icon. He lives like he wants to live—he got an ice cream cone on his face, he driving a Phantom and he got 18 bedrooms in this house, you know? He’s not a dummy. He’s a legend. This nigga will walk anywhere—any mall, any street, anywhere he wants. That’s like some Al Capone shit. He comes from where he comes from, and even if he would change, he would go back because it’s in his blood and it’s in his roots. That’s just the type of nigga he is. I think that’s why he lasted so long in this game.

Zaytoven: You can ask anybody in Atlanta now and they’re gonna be like, “Oh, Gucci Mane, [he’s] my favorite rapper.” The tracks that we laid ten years ago [are] holding Atlanta music up right now.

Coach K: Gucci’s run was raw. He brought a raw, gifted talent, [and] the kids like the real shit. They love the authenticity. Gooch was so authentic, you lived through his music because you could see everything that he was doing—if he was going to jail, getting into a fight, his whole story was documented. At times, he might have kept it too real. But who’s to say? T.I. had an album, Trap Muzik, and Jeezy had trap songs, but Gucci was the epitome of the young boy in the hood, waking up every day in the trap.

Todd Moscowitz: I think he’s one of the most important artists of our time. He’s the source of so much of what’s going on, not just in hip-hop, but in music in general, including the trap EDM stuff. He’s influenced an entire generation of rappers and artists. Beyond that, I personally think that despite his troubles, which are well documented, he’s just a great human being. He is an incredibly deep, thoughtful, and sincere person.

On May 13, 2014, Gucci Mane pleads guilty to possession of a firearm by a convicted felon, avoiding trial in the federal gun case. On August 10, 2014, U.S. District Judge Steve Jones sentences him to 39 months in federal prison, with credit for time served. On September 15, 2014, Gucci receives an additional three-year sentence in Fulton County after pleading guilty to aggravated assault stemming from a March 16, 2013, incident in which Gucci hit an Army staff sergeant with a bottle at a nightclub in Atlanta. He is transferred to United States Penitentiary, Terre Haute, where he remains today. Although the Federal Bureau of Prisons lists his scheduled release date as March 2017, those close to him suggest—without being specific—that he will be home sooner. The Spot is slated for an October 2015 release, and an autobiography is in the works.

Sean Paine: While he’s locked up, that doesn’t mean he’s not working. He’s gonna do a movie. He’s writing his book. I think he said he wrote over 200 songs since he’s been locked up. Those are written songs—that’s different from the punch-in rap.

Coach K: The dude is a poet, man. He’s a real poet. When he sits down and writes, it’s some of the most incredible shit for real.

Mike WiLL Made-It: I talk to Gucci every day. He [sounds] confident and swagged up. Gucci is only 35. He’s never really been out and been there for the whole rollout process of an album and shot videos and toured. He’s still got time to do that.

Todd Moscowitz: [He’s] in shape, plotting every day. He’s got time on his hands and he’s using it all toward thinking about the future. We’re both still figuring out [the specifics of a business relationship], but we have plans to do a bunch of things together. The story isn’t over.

Diwang Valdez

Diwang Valdez