Sometimes I Feel Bad For Kendrick Lamar

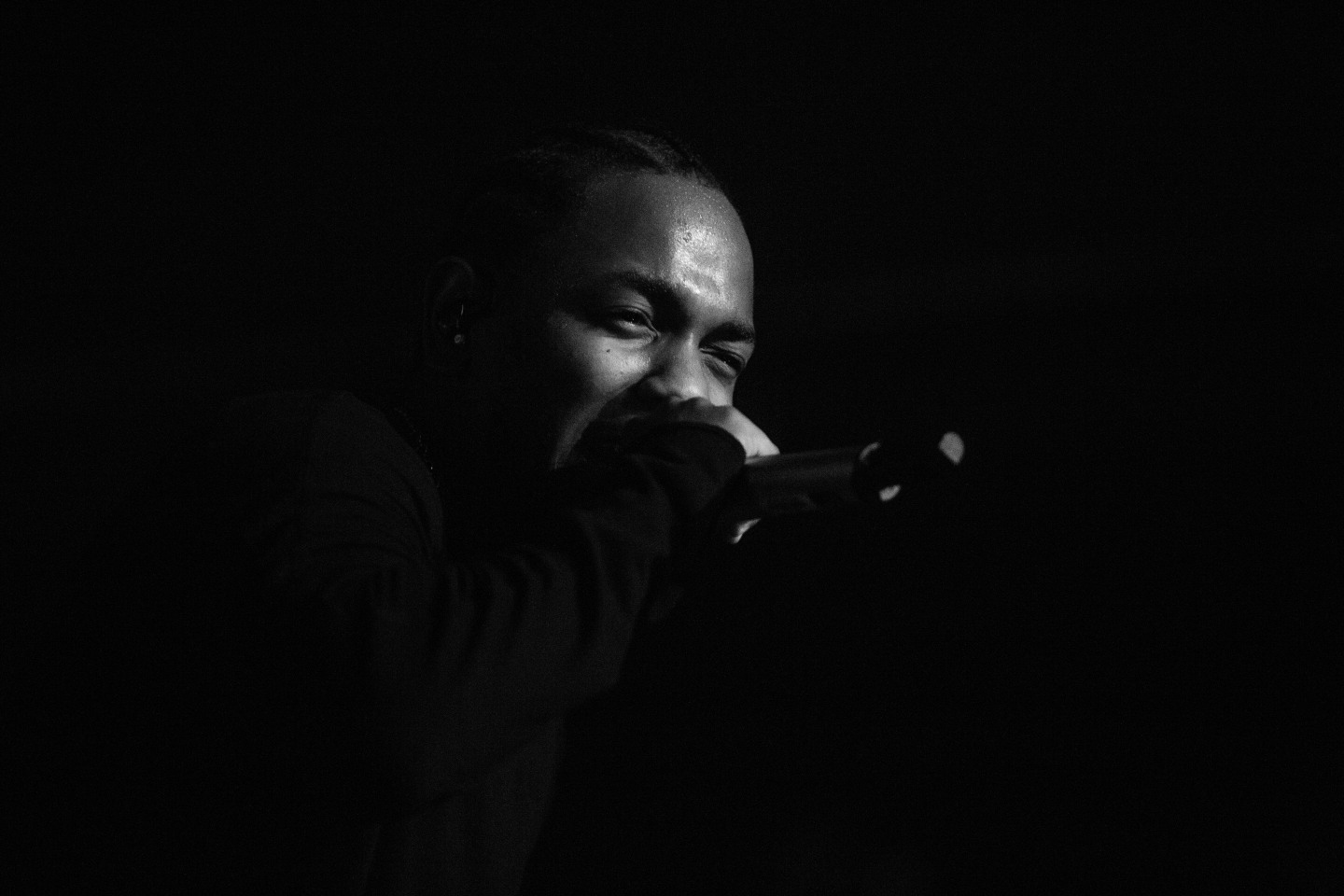

The Compton rapper brought his Kunta Groove Sessions tour to Terminal 5 in New York, where his earnest craftsmanship battled the crowd’s party vibes.

Kendrick Lamar has braids. After sporting a hardy classic fade for a few years and then flirting with mini-twists for a minute, he recently enlisted someone to guide his hair into seven cornrows, tight to his scalp. When I first saw a photo of his new look, I joked about it online, posting a quip that was still getting retweeted weeks later. On Monday night, after leaving his Kunta Groove Sessions show at Terminal 5, a friend concurred hilariously in a text that read only, Braids on football stitches. I walked into a pole laughing.

The hairstyle is fine, and maybe even cute, but it feels notable for being the first time there has ever been anything to say about Kendrick Lamar, Serious Rapper™, that didn’t involve music. Over the course of his career, there have been no salacious relationship details to gossip about, no vague late-night subtweets to parse through for label drama, no paparazzi shots to turn into quick-hitting memes. Even his one bit of headline-news, an incendiary verse on the unreleased Big Sean cut “Control,” could be neatly understood as, Kendrick Lamar cares more about his craft than you do.

Whereas peers like Drake and Meek Mill, both of whom he called out in that “Control” spasm, are full-fledged personas in rap and beyond, Lamar has found success in going the opposite way, leaning into the studio and staying out of the club. On his debut full-length good kid, m.A.A.d city and the 2015 follow-up To Pimp a Butterfly, the Compton rapper established himself as King Kendrick: conceptual artist, grand thinker, perpetual worrywart, the kind of dues-paying kid that older, self-identified “real hip-hop heads” are proud to list as a current fave.

On stage at Terminal 5, for what was billed as an “intimate” performance and originally booked at the considerably smaller Webster Hall, Lamar ran through hits and deep cuts from his repertoire, treating crowd-pleasing bangers like “Swimming Pools (Drank)” and “m.A.A.d. city” with the same enthusiasm as lesser known tracks. There is no impassioned Yawk! Yawk! Yawk! to stomp along to on much of To Pimp a Butterfly, but he dove in anyway, backed by a skilled band of teenagers who helped him translate the cinematic sweeps of his recordings to the stage with a grandeur that's unprecedented for the rapper's live shows. Behind him, a backdrop alternated between red, blue, and purple—not-at-all subtle nods to his stance on gang culture, which he has immortalized on record and in sneaker form.

But for all of his earnest, music-first hard work, there is a disconnect between Lamar and his vast fanbase, which bought 320,000 copies of To Pimp a Butterfly in its first week and pushed it to land a No.1 Billboard debut. An album is a controlled space, conceptualized and executed in a vacuum, but add several hundred drunk partygoers to the mix and its meaning necessarily shifts. Lamar, who deals in motifs of gang life and poverty, blackness and masculinity, hope and fundamental despair, lords over records with excruciating attention to detail. But his auteurial intent doesn't always land in person. When he raps about alcoholism (on "Swimming Pools"), colorism and self-hatred ("The Blacker The Berry"), and mental health ("i"), the songs become disfigured, turned into party anthems under his watch but not necessarily with his consent. In those moments, it’s hard not to feel bad for Lamar. People want a lot of what he has to offer, and a lot of what he doesn't.