Getty Images / Christopher Polk

Getty Images / Christopher Polk

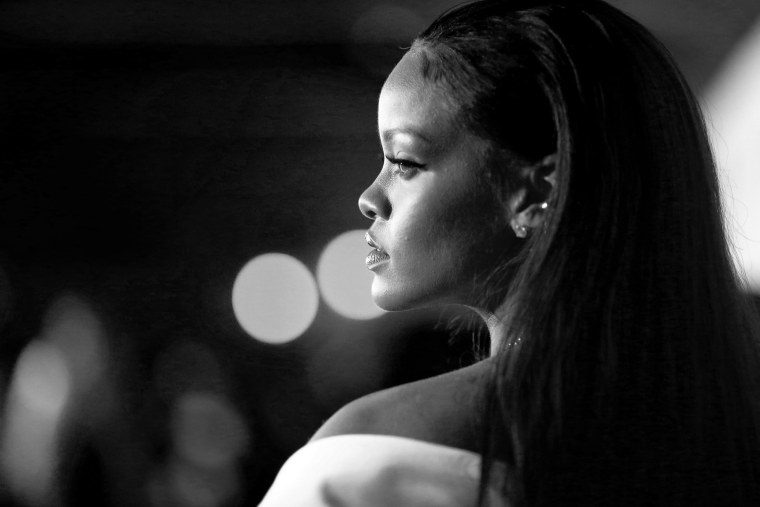

Jay Z was 26 when he released his debut opus Reasonable Doubt, and M.I.A. was 29 when her first album, the paradigm-shifting Arular, entered the world. When I was a little younger, repeating those facts felt useful: my friends and I would often return to them as reminders that we still had time to become our best selves, to produce our finest work, to flower from anonymous, ambitious artists into people who’d wind up influencing entire genres. After all, no artist arrives fully formed. Jay Z famously began his own artistic journey while hustling in Brooklyn; for M.I.A., much of it happened in and around London’s Central Saint Martins College. But for Rihanna, who, at 27, has just released her eighth album, the bulk of that creative self-discovery has happened in public: on Instagram, in paparazzi shots, and on magazine covers. After a decade of pop stardom (and a messy months-long rollout), she has, in Anti, presented her first complete artistic statement.

That’s not to suggest that Rihanna hasn’t made solid music in the past, or that she deserves no credit for the heft of her catalog thus far. On the contrary. Some of contemporary pop’s most defining songs—like “Umbrella” and “We Found Love”—have been hers, sung in the lilty Bajan accent that occasionally glides across a track, like when a pesky paparazzo deigns to obstruct her path. In recent years, as she’s leaned more into the strip club-friendly, trap-adjacent sound of modern hip-hop, Rihanna’s own tastes and sensibilities have become increasingly detectable in her music. It’s clear she has a good ear, and the panache to turn good songs into great ones. Still, her albums have served the significant, if unspoken, pressure of having to pay a lot of people’s bills. For years, Rihanna has functioned like something of a cottage industry, guaranteeing income for songwriters, publishers, record labels, and a global touring industry, all of whom profit directly or indirectly from albums stuffed with hook-heavy singles developed in pop-factory workshops.

On Anti, she’s abandoned that erstwhile formula. Though she was rumored to have spent months and months hosting writing camps in search of material, the album has none of the obvious results that define the Max Martin- and Dr. Luke-styled labor. There are no songs designed to be blasted in H&M dressing rooms, nor any glossy, neon tracks for whom a bright arena stage is a better context than a simple pair of headphones. Instead, the mid-tempo, dancehall-inflected “Work,” featuring Drake and produced by Boi-1da, is Anti’s most club-appropriate proposition. Collectively, its remaining 12 songs are slow and thoughtful, bouncing between pop, rock, and soul. There’s the Hit-Boy- and Travis Scott-produced “Woo,” the dramatic, bass-driven “Desperado,” and, most surprisingly, “Same Ol’ Mistakes,” a cover of Tame Impala’s “New Person, Same Old Mistakes,” with the official permission of the band’s Kevin Parker. (Anyone upset about the cover should consider that her rock group of choice was once Coldplay.) Throughout the album, Rihanna’s voice, once considered her greatest flaw, soars; even when it’s not perfect, it’s confident and ambitious.

Ironically, the critiques that have been lobbed most forcefully at Anti in the days since its release—that it’s largely languorous and overly introspective and, therefore, boring—are actually its greatest qualities. Songs like the hazy ode to weed “James Joint” and the classic soul-referencing “Higher” sound like they were written and produced with Rihanna in mind and with Rihanna in the room—instances of direct creative expression, rather than retrofitted for her after being turned down by another artist. On the album, she’s dictating a new pace for herself and marking the beginning of a new phase in her career, one in which industry demands will have to bend to her whims as an artist, rather than the other way around. In some ways, the shift recalls Beyoncé’s pre-4 hiatus, in which she took her first-ever extended vacation and returned with an album she described as more organic, more personal—an album with more of her in it. Pop stars don’t get to be considered artists until they take breaks from their public selves. Like 4 did for Beyoncé, Anti will force audiences to consider Rihanna an auteur, a tag she, for reasons worthy of an analysis of their own, has long been denied.

Over the years, Rihanna has excelled at reinventing herself with every album cycle, changing her hairstyle on schedule and arming herself with new talking points to match the project’s narrative. With 2009’s Rated R, for instance, she rejected the victim tropes imposed on her by the media in the wake of Chris Brown’s assault, and emerged with a severe haircut, matching dark makeup, and a new, edgy persona. But since the release of 2012’s Unapologetic, she’s amped up that reinvention, transforming before our eyes on a near-weekly basis; now, looking back through the lens of Anti, it appears she was experimenting with her art as much as she was with her style. As we watched her flit from city to city, often with a blunt or a glass of wine in tow, Rihanna was perhaps doing what most artists get to do in private: finding herself.