STR / AFP

/

Getty Images

STR / AFP

/

Getty Images

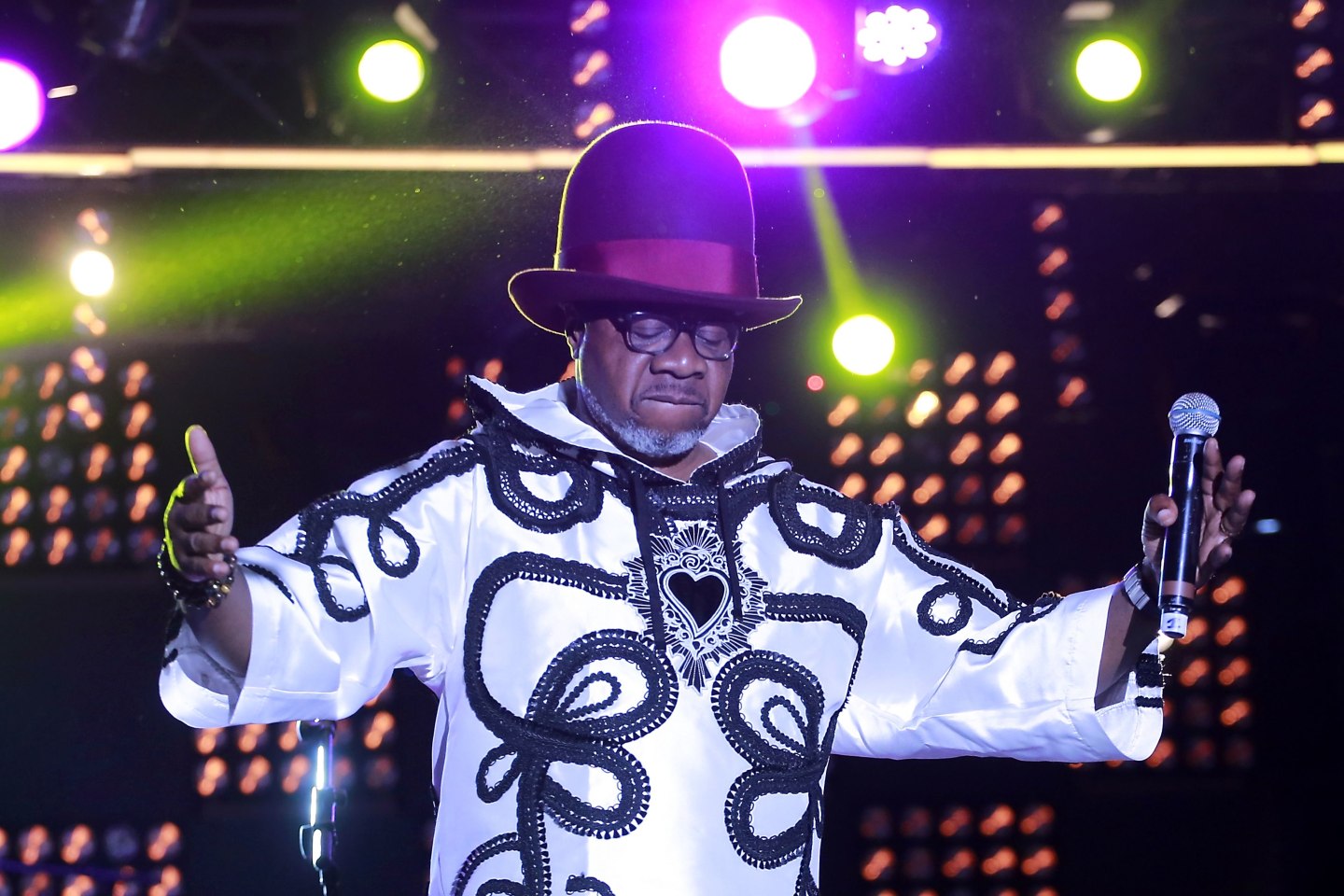

There is a scene in the classic 1987 French-Congolese film La Vie Est Belle, where a character played by the legendary musician Papa Wemba is mistaken for dead after a heartbreak-induced suicide attempt. After eventually being resuscitated, he's thrown into the trunk of a car and driven to a nightclub where his band is performing for a live broadcast without their lead vocalist. Still dazed, he stumbles onto the stage, mic in hand, wearing a shimmering sequined black overcoat. He sings out—hesitantly at first—in his famed velvet falsetto and the show goes on. All ends well and the credits roll over a jubilant dancing crowd. Fin.

Last weekend, when news of the real Papa Wemba's death began to circulate on the internet, many of his fans were in denial. On April 24, 2016, Papa Wemba—born Jules Shungu Wembadio Pene Kikumba—had collapsed on stage while performing at a large music festival in Abidjan, Cote D’Ivoire. His band members attempted to revive him but their efforts were futile, and this time the show did not go on. Papa Wemba, aged 66, passed away before reaching the hospital and the credits rolled for the last time on a one-of-a-kind pop culture genius whose musical and sartorial sensibility has left an indelible footprint on the African continent and beyond. The outpouring of shock and grief rivaled the flood of purple tears (and prose) that was still flowing strong for Prince, another musical polymath and international superstar who had passed just three days before.

To understand the full extent of Papa Wemba’s influence over his four decade-long career, just follow the trajectory of the Congo’s rich music history. In the '50s, Afro-Cuban-inspired rumba was the dance music of the day throughout Africa, but by the mid '60s, a younger generation swept up in the euphoria of soul and rock and roll was deaf to its appeal.

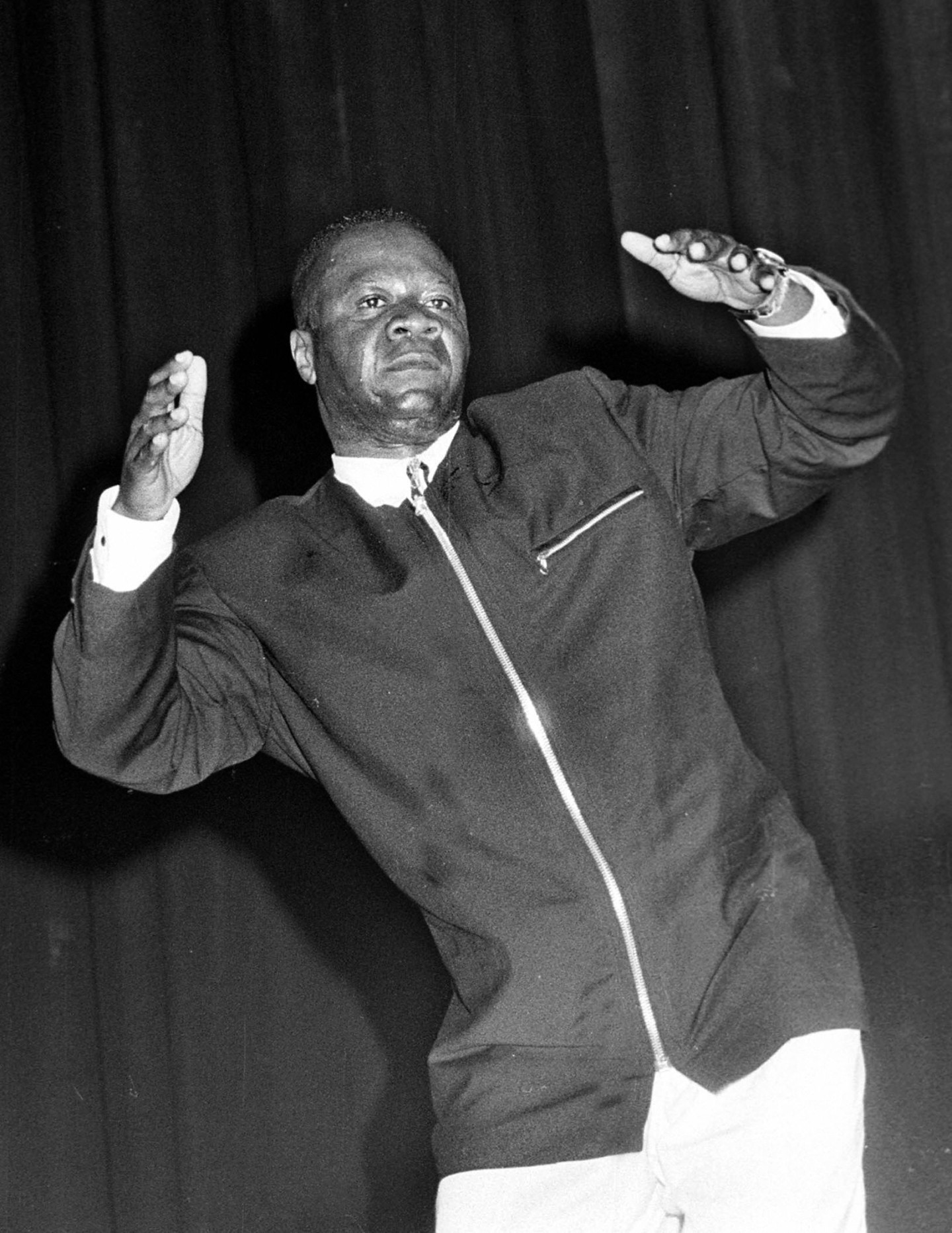

Papa Wemba performing in Abidjan in 1991.

Issouf Sanogo

/

Getty Images

Papa Wemba performing in Abidjan in 1991.

Issouf Sanogo

/

Getty Images

It was a band called Zaiko Langa Langa that gave the local music a much needed shot of adrenaline in 1969. They sped up the tempo, tossed out the horns, doubled down on electric guitars and emphasized the drum kit. Perhaps most important (and similar to what hip-hop DJs would do with “the break” a decade later) Zaiko extended the sweetest part of the rumba, known as the sebene: the part of the song where interlocking guitars weave hypnotic, repetitive rhythm patterns, pushing dancers deeper into ecstatic abandon. Zaiko changed the course of Congolese rumba forever and christened its frontman, Papa Wemba (a.k.a. 'Jules Presley'). With his distinct, lilting vocals, innovative dance styles and flamboyant wardrobe, he became the genre’s definitive rock star.

In the early '80s, as African music increasingly made inroads into Europe under the fuzzy catch-all banner of "World Music," Wemba again sat at the helm of this transition. Splitting his time between Kinshasa and Paris, he maintained Viva La Musica, which played fresh rumba and soukous for the home audience, while simultaneously leading La Nouvelle Generation, experimenting with edgy Congolese music fusions for his European and Asian markets. Wemba’s groundbreaking integration of synthesizers into Congolese music would, in some ways, set the stage for the commercial domination of Coupé-Décalé and afrobeats later on.

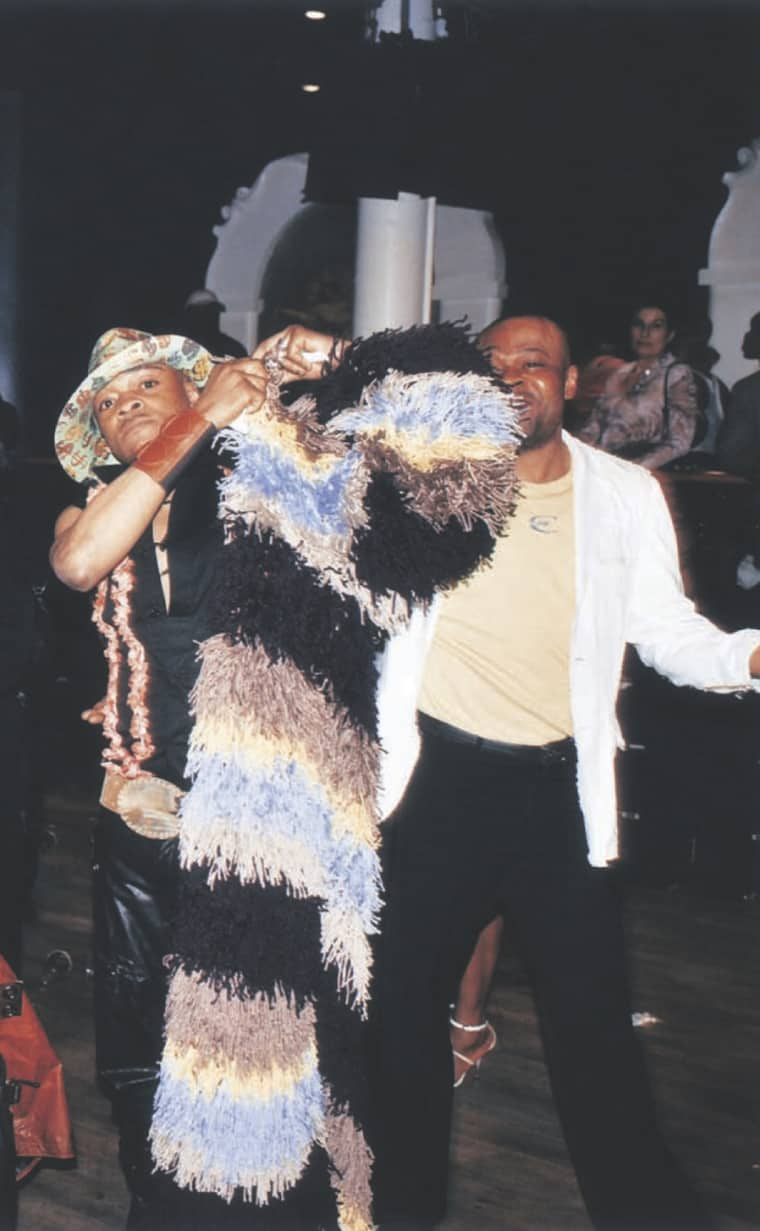

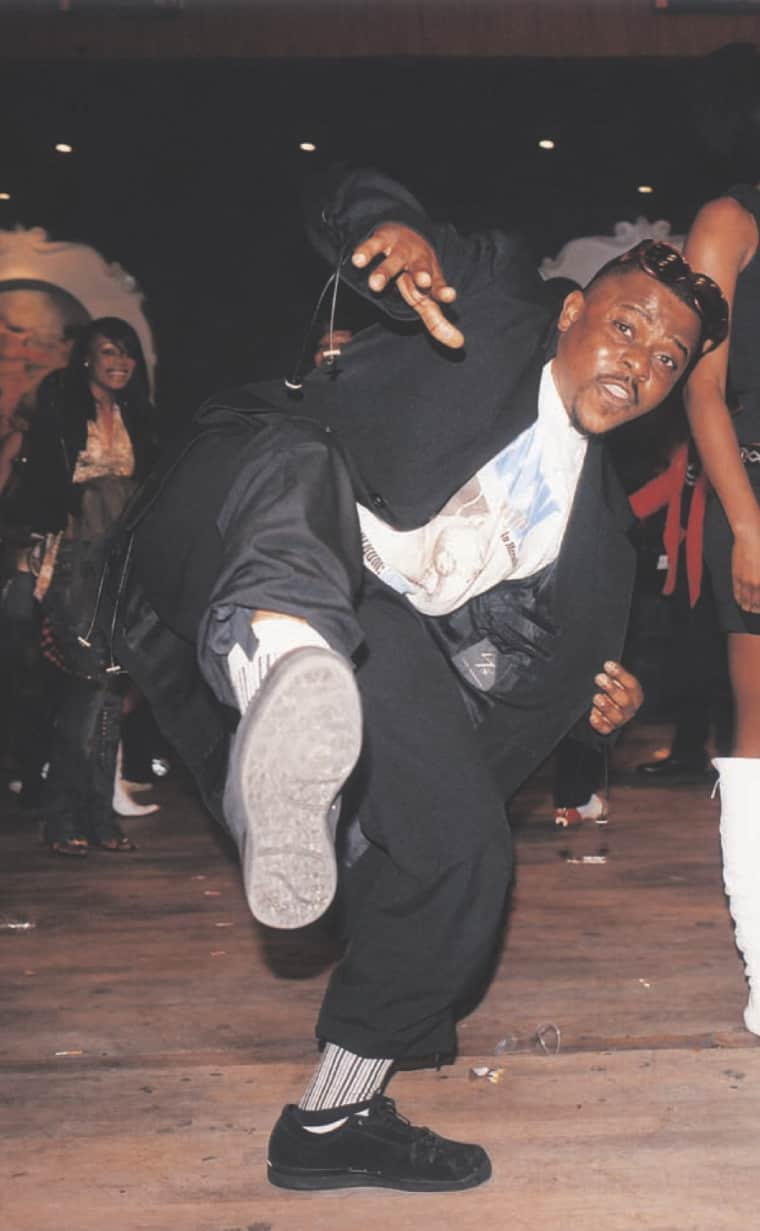

Sapeurs in Paris, 2012.

Liz Johnson Artur

/

The FADER

Sapeurs in Paris, 2012.

Liz Johnson Artur

/

The FADER

Although aesthetically far removed from the scruffy jeans and torn t-shirts of punk fashion, SAPE is rooted in the same rebellious rejection of the status quo.

But Wemba’s influence on contemporary African culture extends far beyond music. Where would ostentatious dandies like Fally Ipupa, Boro Sangui, and Wizkid be without Wemba’s SAPE? A French acronym that roughly translates to 'Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People,' SAPE is a "fashion religion" over which Wemba presides as pontiff. He later became known as "Le Pape de la Sape," the Pope of the Sape. Just as Fela Kuti ruled over his Kalakuta Republic, Papa Wemba was the head of his own “Molokai” village, a commune outside Kinshasa for his band and followers where he mandated the beret as a sartorial necessity. Today, the Sapeurs strut the streets of Kinshasa, Brazzaville, and Paris sharply dressed, proudly showing off their suit labels, and engaging in the occasional style battle. Although aesthetically far removed from the scruffy jeans and torn t-shirts of punk fashion, SAPE is rooted in the same rebellious rejection of the status quo. While punks sought to dirty down, Sapeurs chose to clean up in defiance of their socioeconomic ceiling in war-torn Congo or as immigrants in Europe. SAPE was a rejection of poverty and an aggressive reclamation of dignity. Their sense of style was so striking that the Sapeurs themselves became an inspiration for top designers like Junya Watanabe and Paul Smith. As Papa Wemba himself once put it: “White people invented the clothes, but we make an art of it.”

By pushing Congolese sounds onto a widening global stage, Papa Wemba broadened ideas of African popular music beyond the narrow ghetto of “World Music,” enshrining it as international music. When Vampire Weekend take the kwassa kwassa to Cape Cod or MIA jumps on a kuduro riddim, you can believe Papa Wemba paved the way for that. And now he’s gone, but crowds will be dancing jubilantly to his music for a long time to come. As he declared with the very name of his band, viva la musica. Viva Papa Wemba!