Drew Gurian / Red Bull Content Pool

Drew Gurian / Red Bull Content Pool

With last year's Chi-Raq, Spike Lee tackled Chicago’s harrowing gun violence epidemic with an absurdist musical. Inspired by Aristophanes' comedy Lysistrata, it revolves around a plot by the city’s women to create peace and harmony by banning sex until their men put down their weapons.

And if that’s not enough for you, this thing also had Wesley Snipes in a bedazzled eye patch and Samuel L. Jackson as a debonair fourth-wall-breaking narrator and what truly appeared to be a real life version of auto insurance's famed The General and Nick Cannon in a lead role as a ruthless gangster. And every last line of dialogue is delivered in verse. The descriptive word I’d reach for here is insane: at times, I could not believe I was seeing what I was seeing.

A few critics destroyed it; others put it on the very top of their year-end Best Ofs. The fiercest reaction, however, came from the city of Chicago. As Chance The Rapper tweeted at the time: “You don't do any work with the children of Chicago, You don't live here, you've never watched someone die here. Don't tell me to be calm.”

There’s a lot more to say about Chi-Raq, and Spike’s right to make a movie about Chicago, and Spike’s right to make a movie about Chicago like this. But there’s also this to say: how many other directors, three decades in, still have the drive and the juice to make something that insane? At 59, Spike may not have the same audience he once did, but he’s still as game as ever to kick up a shit fit.

All of which is to say: there’s no bad time to talk to Spike Lee. Ahead of his sit-down with Nelson George this past Monday at the Red Bull Music Academy, Lee was good enough to give The FADER a call.

Your RBMA talk today is about your use of music. So it seems right to ask first about some of the times that music has used you. One really great example is the intro on The Roots’ Things Fall Apart, which samples Mo' Better Blues. I feel like there are Roots fans that can recite that whole chunk of dialogue by heart: “The people don’t come because you grandiose motherfuckers …” When’s the first time you realized they’d co-opted your movie so nicely?

To tell the truth, I don’t remember. They got the permission but it wasn’t from me. They must have gotten it through their record company. But any time people do that, I take it as as a compliment, I take it as an homage. It’s all love. I’m a big Roots fan. I’m a big, big Questlove fan. We’re all family.

You keep up with references to you in hip-hop in general?

Nah. Somebody did a Google search, it was like 200 rap records that I’ve been mentioned in. [Laughs] “I’m smoking that joint like Spike Lee,” shit like that.

I also always think of Jay’s I be Spiked out, I can trip a referee.

What he say?! [Laughs]. Yeah, so I always feel like it puts a smile on my face. It’s funny and, also, it shows that the impact of the work we’ve done. It has really become part of the culture.

So you’re talking with Nelson George tonight…

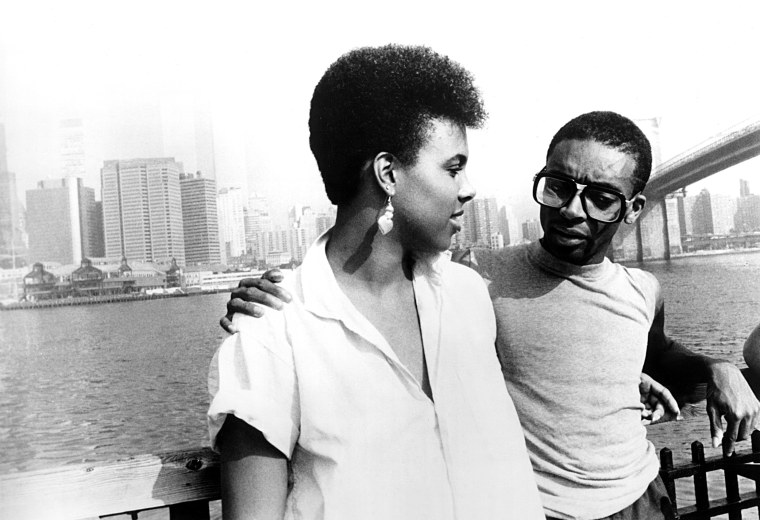

Yes, it’s gonna be a conversation between myself and my good friend Nelson George. A lot of people don’t know this but Nelson was one of the investors in She’s Gotta Have It. 1985. This August 9th will be the 30th anniversary of She’s Gotta Have It.

Wow. Have you seen it recently?

I’m gonna have to look at it sooner or later. But these years fly. I have two children in college. They’re growing up before my eyes. Time waits for no one!

40 Acres & A Mule Filmworks

40 Acres & A Mule Filmworks

What are they studying?

Oh they’re in the film school in NYU. One’s a junior, one’s a freshman. They grew up on sets. The thing is that, my wife and I, Tonya, we did not force this on them. This is something of their own will. But we support them, very much.

Your last feature, Chi-Raq, inspired some heated responses. Did you expect to be walking into that kind of situation?

Oh here’s the thing: the response it got, Chi-Raq, is not new. I mean, I met with this lady who was a reviewer on School Daze and she said it set the race back 400 years. She’s Gotta Have It: Nola Darling was a stereotypical image of an oversexed black woman. Do The Right Thing: this film will cause riots all across the country. Mo’ Better Blues: I was anti-semitic. Jungle Fever: Spike hates interracial relationships. So I mean, no, it’s not new.

I never been one to hold my tongue, and there’s some things I felt I needed to respond to. It’s not like I go into a film looking for a fight. But I'm not ducking one either. The subject matter I’ve chosen over the years, the reactions on both sides: that’s a good thing. Through three decades of doing it, it gets people talking.

Well at the very least, I think even critics of that film could appreciate how outlandish it was, and how much energy you still have left to expend. A lot of directors, after enough movies, they maybe start mailing it in a little.

I don’t think that’s gonna happen to me. That’s not gonna happen to me. I’m doing what I love, and there’s nothing else I wanna do. One of my film heroes, Kurosawa, the great master Japanese filmmaker, he was making films to his early eighties. So I got a lot more stories to tell. I got a lot more fire and brimstone left.

Yeah, and some of his best movies, too. Ran was a later one. Rashomon, though, that’s the one I always think about.

Rashomon was really the genesis of She’s Gotta Have It. You had these various people talking about a murder [in Rashomon] and I took that aspect of it and turned it into several people with their response to Nola Darling, this woman who was juggling three men.

Daiei Film

Daiei Film

Do you ever struggle for inspiration?

Mmm. Nah. The struggle’s for the money. I got inspiration. Inspiration not the problem, never been the problem. The problem at various times is getting the financing for my films.

When was it easiest for you to get financing?

I mean, there was a string where I was at Universal. Do The Right Thing, Jungle Fever, Mo’ Better, Clockers, Crooklyn. It’s like seven films right there, all from Universal Pictures. But that stuff changes. People move out. The world changes. So you gotta keep plugging.

You feel like you’ve moved well with the times? You’ve figured out some of these new distribution models?

For sure. Chi-Raq was the first theatrical release for Amazon Studios. We’ve been very good over the years at adjusting—at bending all form and shape—to get stuff made.

One of the more memorable parts of Chi-Raq was John Cusack’s preacher character. He really goes for it! Did you have to work with John to find just the right level of intensity?

Well, John’s a great actor, number one. But what a lot of people don’t realize is that that character that John played is a real life person. His name is Father Michael Pfleger, whose church is Saint Sabina on the south side of Chicago. So John was able to study Father Pfleger on various Sundays in church. And a lot of dialogue was taken from Father Michael Pfleger's sermons, too.

We wanted that scene to not just be a eulogy about this young girl murdered in a drive-by. No. What we wanted was to get at the reasons why she was in that [situation]. What we tried to do in that scene is explain why the situation in Chicago is the way it is, today, presently. And that’s why that scene is like 15 minutes, too.

OK, so back to the criticism of the movie for a minute. I think a lot of people felt that the heart of the backlash was that you, an outsider so closely associated with Brooklyn, was coming in to do a movie about Chicago. Like, would you have been OK with an out-of-town director coming in and trying to do this kind of grand, definitive movie about the problems of Brooklyn?

First of all, has anybody seen Clockers?! Clockers dealt with the same thing. So I find that argument, as Mike Tyson would say, ludicwous. Ludicwous! But, you know, history will show. We’ll see what history says. I’m confident that we’ll be on the right side of history with this film, Chi-Raq. I understand people in Chicago being very sensitive to what’s happening in it, and to seeing someone coming in who is from ohhh New York City ohhhh. But the fact remains that you can’t hide this stuff.

Today, May 2nd—this year so far, 165 people have been shot and killed in Chicago. 969 have been shot and wounded. That’s a total shot of 1034. In just the first month of the year—the year of our lord, 2016! In just the first month, 53 people were shot and killed, and 247 were shot and wounded. So people talk all they want, but the fact remains that Iraq is safer than the south and west sides of Chicago. I’m not gloating. Those numbers don’t make me happy. But the truth is the truth.

Would you be OK with an out-of-town director making a similar movie about Brooklyn? Can’t you imagine someone almost needing your permission to do that?

First of all, why would someone need permission to make a film about Brooklyn? That doesn’t make any sense. I don’t understand that. You don’t need permission from me to do anything you wanna do!

I hear you. What about you and Brooklyn? Is there anything in modern day Brooklyn that you’d be interested in tackling? Do you think there’s a great movie in gentrification?

Oh yeah. We’ll see. [Laughs] We shall see what we shall see!

40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks

40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks

Before you go, I have to ask about one of my favorite movies of yours, He Got Game …

Sunday was the 18th anniversary of He Got Game. 18th. We think that its the best narrative American basketball film ever. And the best non-narrative basketball film is Hoop Dreams. In my opinion. So I spoke to Rosario [Dawson], I spoke to Denzel [ Washington], and Ray Allen, I exchanged texts with him. Hopefully we’ll get to revisit those characters. Everybody wanna do it. It’s always a question of getting Denzel on board. It’s very hard to get that film without Denzel.

But La La wants to do it, I wanna do it, and Jesus wants to do it. And I’ve always felt, you can’t lose when you have Jesus on your side!