Jemal Countess/Getty

Jemal Countess/Getty

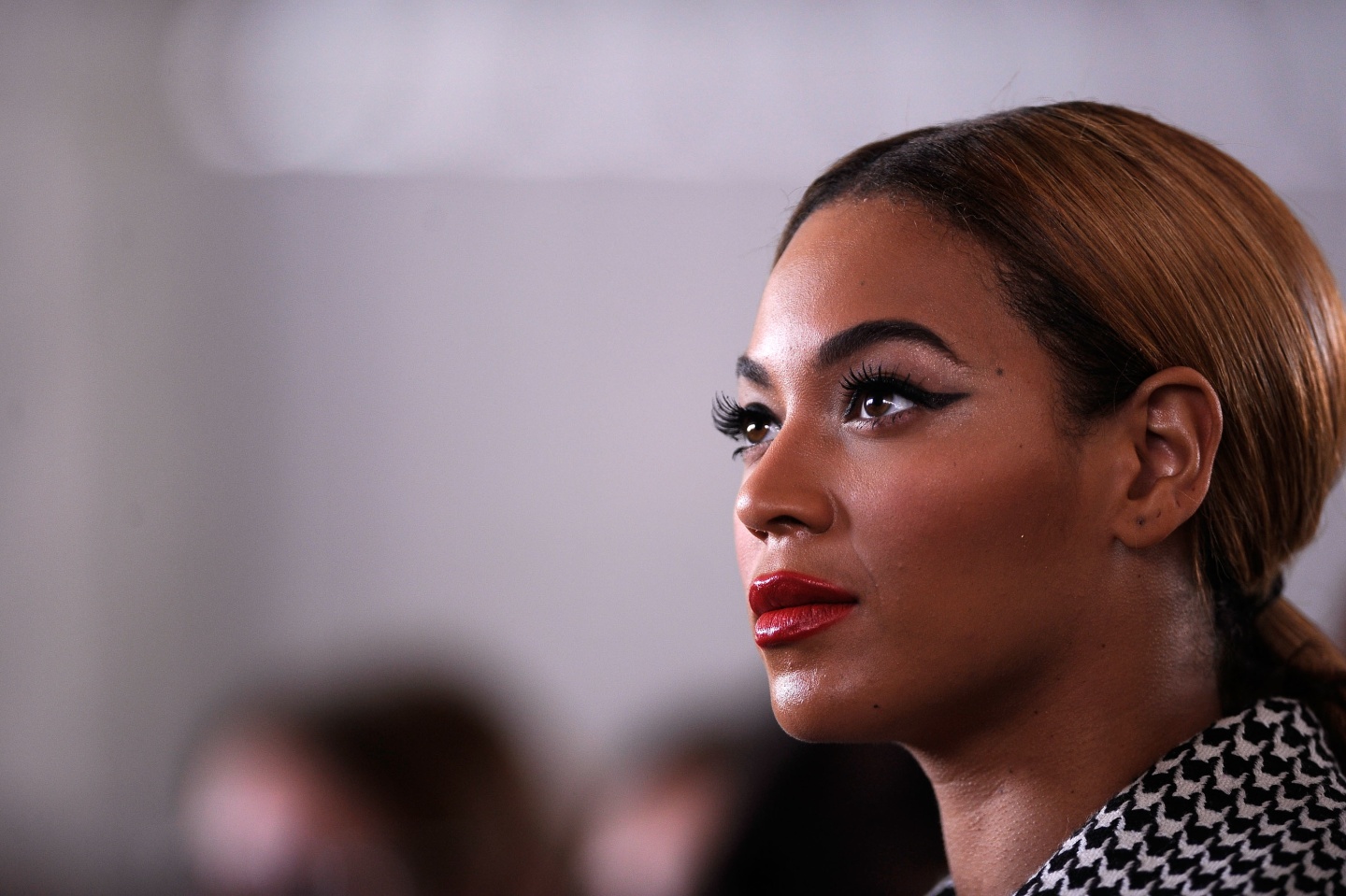

Before she started work on 4, it was hard to see what heights remained for Beyoncé to scale. After three hugely successful solo albums, 16 Grammys, and a Golden Globe nomination, she seemed unstoppable. But underneath the surface, not all was well. After wrapping a 108-date, 11-month-long global tour in February 2010, she was also, as she explained in 2011’s Life Is But A Dream documentary, "overwhelmed and overworked." Physically, mentally, and creatively drained, Beyoncé knew that something needed to change.

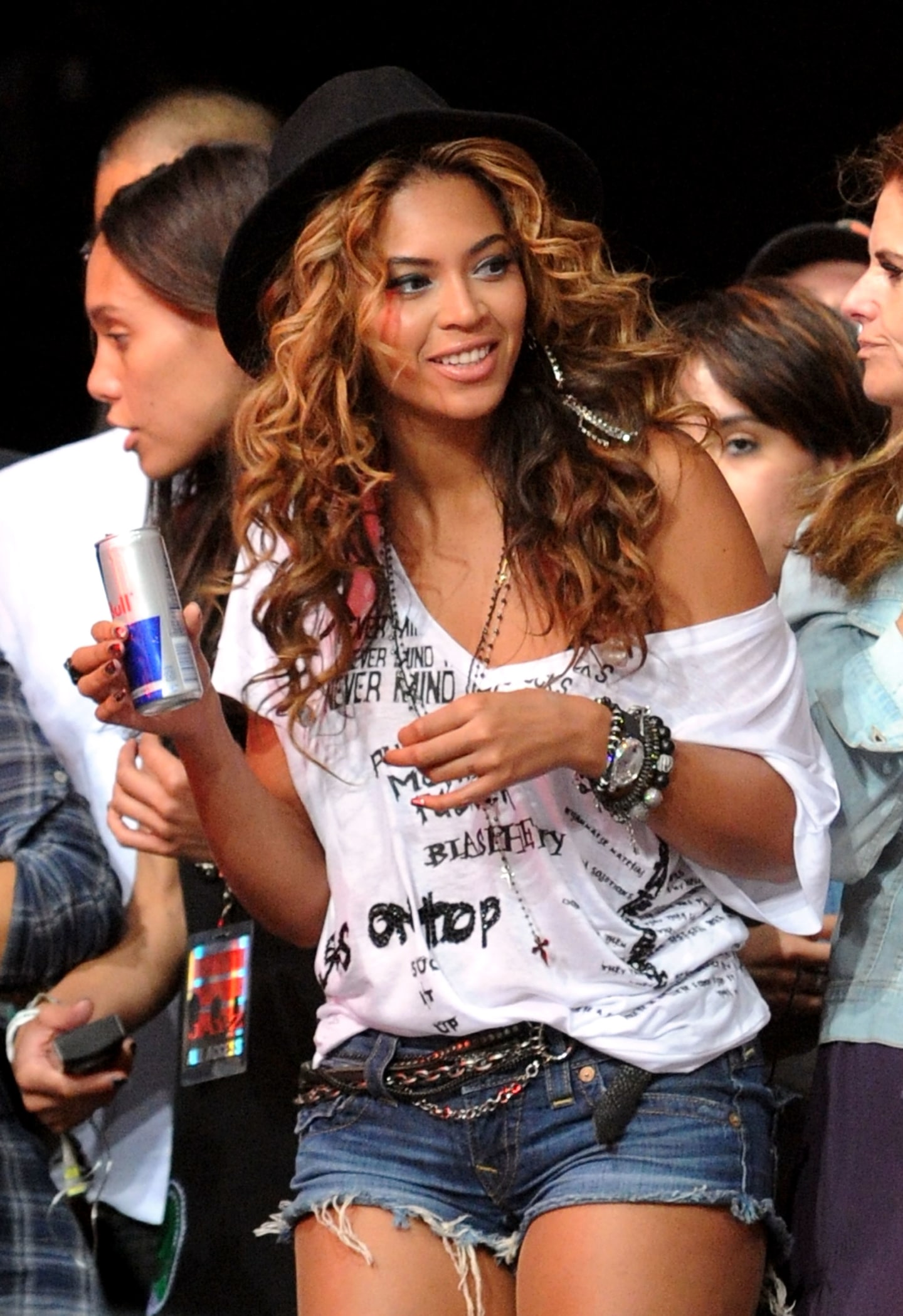

After having finished editing the accompanying tour DVD/CD for the I Am… tour, Beyoncé, on the cusp of turning 30, did something she hadn't done since she was 13 years old: she took time off. She went on vacation; she ate at New York restaurants like the buzzy The Spotted Pig and the quaint brunch spot Buttermilk Channel; she picked her nephew, Julez, up from school; she attended international art fair Art Basel in Miami with Jay Z; she went to see Grizzly Bear play in Williamsburg, and she did a lot of cooking (apparently she can do “good things with oxtail”). The new sense of ease was reflected in the way she dressed. Around this time, Beyoncé’s off-duty and on-duty style started to meet more in the middle: she wore a distressed shirt which read “Girls On Top” to Coachella in 2010, and showcased a more relaxed personal style away from the stage.

Beyoncé’s new approach to life signaled a move away from Sasha Fierce, a character that had come to life during the “Crazy In Love” video shoot in 2003 and had dominated her life for the two previous years. This alter-ego was a robotized, steely pop superhero figure that starred in the ambitious but muddled concept of 2008 album I Am...Sasha Fierce, on which Beyoncé crudely split the two sides of her persona straight down the middle. The existence of Sasha Fierce helped Beyoncé, naturally shy and reserved, become a powerhouse on stage. But it also added another layer of distance between the artist and her audience, at a time when the idea of the aloof, otherworldly megastar was being steadily challenged by tell-all social media and girl-next-door normalcy. Towards the end of the 4 campaign, Beyoncé joined Instagram, giving fans a glimpse into her life.

Beyoncé at Coachella, 2010

Noel Vasquez/Getty

Beyoncé at Coachella, 2010

Noel Vasquez/Getty

In 2016, Beyoncé has not only cemented her status as music’s biggest superstar, but also her legacy as an artist, using that hard-won fame to create challenging bodies of work in the shape of BEYONCÉ and Lemonade. That shift started with 4, a defining statement of an album that signaled an artistic reinvention at a time when it would have been much easier for her to play it safe and follow the status quo. Keen to reveal more of herself both in the music, the accompanying videos and the areas of her life she allowed to appear in the media, 4 represented a relative dropping of her guard, and the natural evolution of a megastar.

An important part of the creation of 4 was her killing off the Sasha Fierce character, the first in a series of actions that reflected her artistic confidence. “I don’t need Sasha Fierce anymore,” Beyoncé told Allure in 2010. “I’ve grown...I want people to see who I am.” That same year, she also parted ways with her long-term manager, her father Matthew Knowles. "It was scary but it empowered me,” she says of her move, in 2011’s frank Year of 4 documentary. “I wasn't going to let fear stop me.” Her language made her desires to stand on her own two feet plain: to fully put into practice the women's empowerment ethos she and Destiny’s Child espoused on 1999’s The Writing’s On The Wall through “Independent Women, Pt. 1,” “Survivor,” and elsewhere throughout their discography.

In 2010, Top 40 R&B was slowly being sucked into the steadily building, singles-lead EDM vacuum. Against this backdrop, 4 looked to place the focus back on albums as an artform, aiming to re-establish R&B as a mainstream concern. (It’s notable that, since its release, Beyoncé has used singles only to augment the larger artististic statements of her 2013 self-titled release — which could initially only be purchased as a whole album — and this year’s second visual album, Lemonade.)

4 placed sonic experimentation front and center, with a myriad of collaborators — The-Dream, Tricky Stewart, Shea Taylor, André 3000, Kanye West, Switch, Babyface — to help facilitate that. With their help, Beyoncé drew from the musical influences (Prince, '90s R&B, vintage soul) that had shaped her musical history but that hadn’t always bubbled up to the surface in her music. While she had always executive produced her solo albums, 4 brought a renewed sense of ownership. "B was the main producer, as every idea had to pass her approval and the bars that she set,” 4's recording engineer DJ Swivel told Sound on Sound in October 2011. “Ideas would come in and she'd say 'OK, that's great, but let's add live drums to this part,' you know?.” She also wanted the album to capture her own sense of urgency. "She can knock a song out in an hour, and it will sound incredible,” Swivel said. “I remember one day we worked for 36 hours straight, and she cut six entire songs with leads, [background vocals], and comps. I think she even managed to squeeze in a couple of business meetings too!”

Inspired initially by afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti, early recording sessions were undertaken with the band from the Broadway musical, Fela! “I loved his drums, all the horns, how everything was on the one,” she told Billboard. “What I learned most from Fela was artistic freedom: he just felt the spirit.” In fact, according to an annotation left by The-Dream on Genius, a whole album of Fela-inspired songs was recorded before 4 emerged. “We did a whole different sounding thing, about twenty songs...That’s why there’s so much of that sound [on] ‘End of Time.’”

At some point between I Am...Sasha Fierce and 4, a strive for perfection which had been instilled in her since a young age through pop troupe Girl’s Tyme (which she joined at the age of nine) and Destiny's Child, was replaced with a desire for emotional directness. (As she'd later say on BEYONCÉ's “Ghost,” perfection is so...ugh.) So, rather than deliver an album of glowing love songs about two ludicrously rich and famous megastars, 4 is peppered with the ebbs and flows of a real human relationship, delivered with sincerity. Even the loved-up New Edition throwback “Love On Top” acknowledges love's struggle (Nothing's perfect, but it's worth it/ After fighting through my tears), while “I Care” bubbles with the kinetic energy of someone who's just walked out of an argument. The pre-Channel Orange era Frank Ocean co-write “I Miss You,” meanwhile, sets a lyric about being far apart from someone you love in the sort of low-key ballad context Beyoncé hadn't touched before. Swapping the elegant bluster of songs like “Halo,” it feels tactile, close.

In many ways “End Of Time” — a pulsating melange of blaring horns, splashy marching band drums and a central vocal that fizzes with pure joy – laid the foundations for 4. Fusing different genres and sonic ideas, the track also drew from the cooler extremities of the mainstream, with the slow-burn intro built around a looped sample — apparently sung by co-producer The-Dream — of the lyric don't fuck with me/ don't fuck with me from Jai Paul's “BTSTU” (Drake would also lift the same line for that year's “Dreams Money Can Buy”). Alongside the Boyz II Men-sampling “Countdown,” itself a sort of genre-less fusion of trap, dancehall, and R&B, “End Of Time” also showed that celebrating complicated but ultimately blissful matrimony needn't be boring, or that bangers in 2011 needn't be straight four-to-the-floor bludgeoners.

Keen to showcase the album’s warmth alongside its desire to push the sonic envelope, Beyoncé preceded 4’s release with two songs: the experimental, stomping “Run The World (Girls),” and the sensual ballad “1+1.” Making its online debut via an iPhone video shot by Jay Z backstage at American Idol, “1+1” felt like a sneak peek directly into the real world of Beyoncé. Watched on by mom Tina and nephew Julez, Beyoncé sings the song into a mirror, eyes clenched shut, her voice — which, as she told Dazed, now utilized the “brassiness and grittiness” that people heard in her live performances “but not necessarily on my records” — sometimes distorting in the phone camera.

Even the fairly straight ballad “I Was Here” — co-written by Diane Warren and Ryan Tedder — features a raw vocal that feels like it's about to burst with emotion. “[That album] is where she shifted away from radio in a sense,” Tedder told The FADER via phone, going on to explain that “I Was Here” was the last song finished for the album, completed on a private jet chartered by Beyoncé's label somewhere over America. “This was a song that impacted Beyoncé tremendously and it was like, 'This is my statement as a human being on earth.' I wanted to capture that as much as possible.” Despite being the album’s one ode to full-on schmaltz, “I Was Here,” donated for World Humanitarian Day in 2012, is an important statement, representing Beyoncé starting to more publicly use her fame to shed light on social justice issues. Since then, she’s publicly supported the Black Lives Matter campaign, raised money for the Flint water crisis, and honored the memories of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner, by inviting their mothers to appear in Lemonade.

The influence of 4 is palpable in the sound and textures of Beyoncé’s music today, as the step she needed to take before she could harness the intense rawness that carries a song like “Freedom,” or the soulbaring roar of “Don’t Hurt Yourself.” But one residual effect of 4 had nothing to do with the music at all. Burned by the fact the album leaked a full six weeks ahead of schedule, Beyoncé would release its follow-up, BEYONCÉ, as a surprise attack, dropping it on iTunes without warning. Here was an artist who had established herself in her own lane, both musically and in terms of cultural influence, not only no longer playing by the rules but actively dictating them. Emboldened by 4’s emotional honesty and focus on the ups and downs of married life, she also nudged open the front door that would eventually be knocked off its hinges by Lemonade. It’s revealing to consider 4 as a forbear to those albums, too: lines can be drawn between the anger that permeates Lemonade’s first half and “I Care,” the throwback joie de vivre of BEYONCÉ’s “Blow” and “Love On Top,” and the frank sexual confessions of “1+1” and “Rocket.” Without 4 laying the foundations for Beyoncé as a re-energized artist, you’d imagine the next step would have been a neatly packaged greatest hits album. Instead it was a launchpad for phase two of a career that feels like it’s getting more and more interesting with every album release.