In 1991, on the occasion of the sixth-ever MTV Video Music Awards, Prince showed the world his ass. He mounted the stage wearing a canary-yellow lace jumpsuit — to match his custom-built Yellow Cloud guitar — and performed “Gett Off” alongside the New Power Generation. The seven-minute orgy-as-performance was flawless, but in the weeks, months, and even years that followed, it was his butt that led the story. Of course, that night was neither the first nor the last time that Prince would wear an assless outfit — but it was the first time he did it before an audience that numbered in the millions. The look, and the moment, quickly became a proto-meme, referenced at the subsequent VMAs by a flatulent, flying Howard Stern and, I assume with confidence, in many a Halloween costume later that fall. It was a pop culture reference that became a joke in itself, the sort of spotlight-stealing thing the VMAs and VMA attendees have since perfected — think Britney Spears’s and Christina Aguilera’s kiss, Lady Gaga’s meat dress, or Kanye West’s impassioned defense of Beyoncé.

And that is, after all, the point of the entire thing. According to Van Toffler, a former Viacom executive who worked on the VMAs for 28 years, the plan is no plan. “[We] put those chaotic elements in the room together and then we kind of let go. We don’t produce things really tightly the way other awards shows might,” he told Billboard last year. (Perhaps tellingly, Toffler also produced the Super Bowl halftime show that played host to Janet Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunction.”) The VMAs’ mandate, he said in the same interview, is to get chatter going: “We love when people talk about the event.” Before the advent of TMZ and video-driven social media, the VMAs were a place where artists could stake their relevance while giving a controlled glimpse into their personal life, building on an identity they may have hinted at in music or interviews, and/or wilding out if they wanted to. Once a year, being in a room full of their peers looked like a party, not a punishment — a drunk prom chockful of industry-grade tea. The show, as assessed in a 2004 New York Times story, “[reflects] the struggle by networks and advertisers to walk the fine line between being provocative enough to attract attention and mild enough to avoid outrage.” Spectacle first, no press is bad press. Madonna proved as much with a controversial, underwear-revealing performance of “Like A Virgin” at the inaugural 1984 awards.

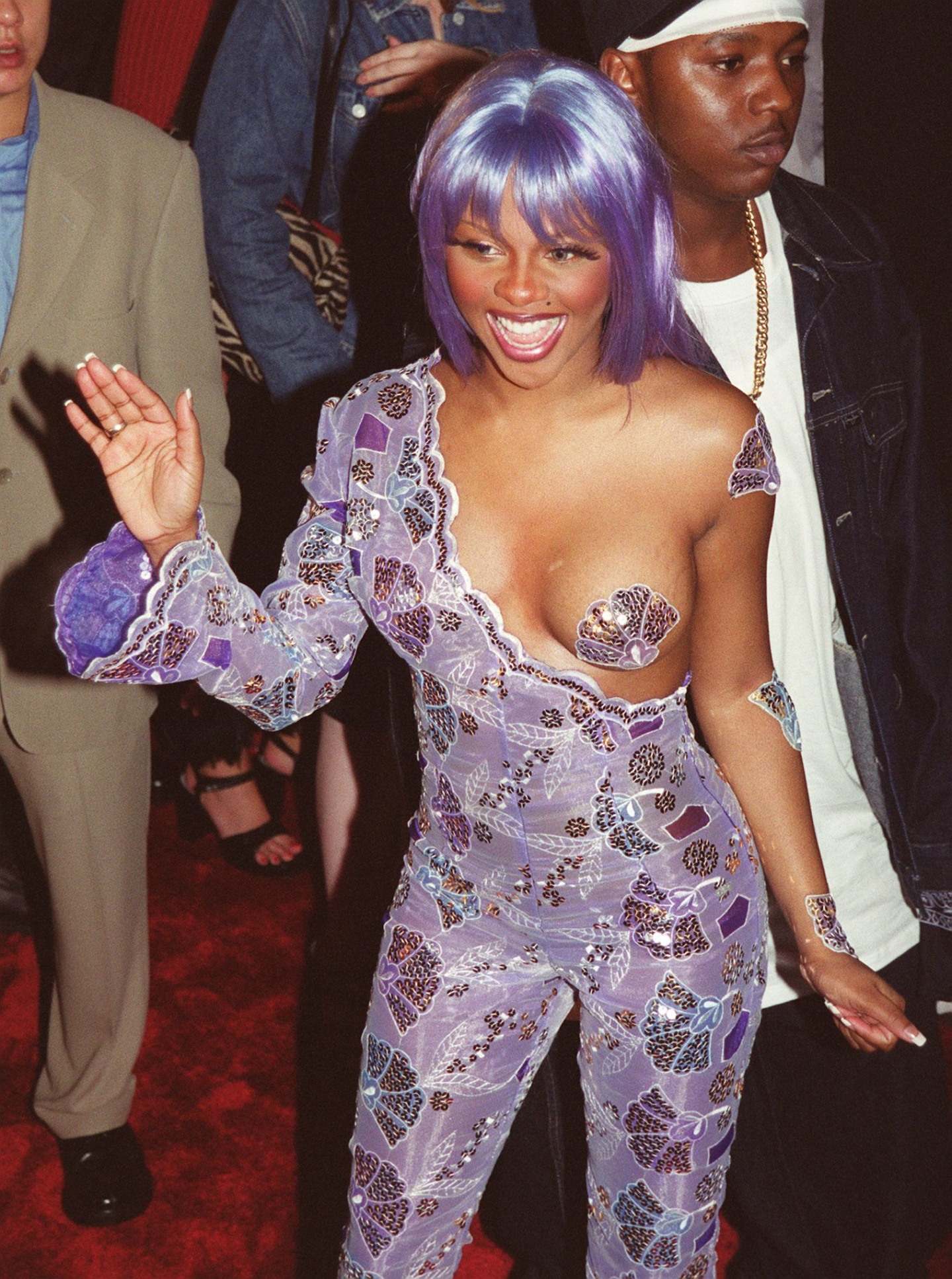

That shifting fine line — the one that, just barely, distinguishes “attention” from “outrage” — has reflected the zeitgeist and broader social climate for decades. That’s why, like Prince’s butt, body parts have historically been at the forefront. Before social media helped direct national and global conversations to issues like cultural appropriation, rape culture, and gender and racial privilege, the most radical thing you could do in public was expose a body part — Lil Kim’s loose left breast, fondled by Diana Ross; Rose McGowan’s entire body in that now-iconic dress; Britney’s nude, bejeweled thong get-up. For decades of pop culture, bodies as sexual entities were recast as emblems of acceptable youth in revolt, and viewers wanted in.

Scott Gries / Getty Images

Scott Gries / Getty Images

For better and for worse, the VMAs are where the borders of mainstream culture are negotiated in public.

Henny Ray Abrams / Getty Images

Henny Ray Abrams / Getty Images

Other VMA moments, too, mirrored the cultural climate of any given era. Puff Daddy being joined by Sting to memorialize Biggie at the 1997 awards gaudily echoed a defining moment in rap’s crossover; Eminem’s provocation at the 2000 VMAs signalled the beginning of the end of the boy band era; Miley Cyrus and Robin Thicke’s twerkstorm in 2013 introduced both the dance and the concept of cultural appropriation to people who’d heard of neither; Kanye’s touching speech-turned-stoned announcement of his presidential ambitions just last year pre-empted the pageantry that is this election cycle.

All along, the focus on culture over music has guided the VMAs as an awards show with a sensibility markedly different from that of, say, the relatively buttoned-up Grammys (or Oscars or Emmys or Tonys). While the Recording Industry Association of America, the organizing body behind the Grammys, is tasked with the relatively high-brow job of selling records and protecting recording institutions, MTV sells the idea of music (and also television ads and audience data). And so rather than simply celebrate the people who earned the most for the industry in a given year, the VMAs fulfill a different role: they wackily, shamelessly, and offensively bottle up youth culture, via celebrity interactions and red carpet looks, and present it as a (monetizable) caricature.

In the process of developing an awards show that aims to compel viewers while appeasing advertisers, MTV made the VMAs a place where trends and topics could be tested in real-time to a focus group of millions. For better and for worse, they are where the borders of mainstream culture are negotiated in public. Social media, for a while anyway, seemed to pose a threat to that equilibrium. But, combined with shifts in celebrity culture, the rise of Twitter as simultaneously a driver and gauge of popular taste has allowed the show to remain relevant, if cringeworthy, from year to year. In order for commentary to bubble up, people have to have something for comment on, and in exchange for a massive platform through which to promote our their own interests, artists and celebrities give MTV that something.

Against the backdrop of an unprecedented media environment, and with low VMA ratings in recent years and general uncertainty at Viacom in general, the pressure to deliver is even higher. According to TMZ, Kanye has been given “free reign” to do whatever he wants at this weekend’s awards. But as public attention fixates increasingly, and rightfully, on politics and social justice, I suspect there will be fewer nipples freed and more wokeness demonstrated, in the style of Fiona Apple’s infamous 1997 VMA acceptance speech: “What I want to say is: everybody out there that’s watching, everybody that’s watching this world, this world is bullshit. And you shouldn’t model your life about what you think that we think is cool and what we’re wearing and what we’re saying and everything. Go with yourself.”