Courtesy of FX

Courtesy of FX

Bokeem Woodbine wasn’t much interested in acting. What he was interested in was a tattoo: the continent of Africa, on his right bicep. But he was just shy of 18, only intermittently employed, and he didn’t have the money. So Woodbine dreamt up a one-time hustle on how to get the cash: he’d do some work as an extra. He found a casting magazine, Backstage, and an open audition for a movie shooting in his neighborhood, Harlem, New York. The year was 1992; the movie was a soon-to-be street-classic called Juice. He showed up and got the gig, the money, and — shortly after — the tattoo of Africa.

It was the inauspicious seed of a singular, wayward career. Woodbine rocketed through the ’90s, working with auteurs like Spike Lee and the Hughes Brothers, popping up in Tupac videos, and hamming it up in big-budget action-comedies with Mark Wahlberg. And then he disappeared. For over a decade starting in the early 2000s, he had no true roles of note. More than likely, you hadn’t thought of the name “Bokeem Woodbine” for years. That is, until Fargo.

At this Sunday’s Emmy Awards, Woodbine may win for his work on the second season of Fargo, FX’s elite crime series, as the bizarrely droll Kansas City crime-syndicate tough Mike Milligan. It’s a longshot — he’s nominated in the Outstanding Actor, Limited Series category, up against bigger names like The People Vs. OJ Simpson’s David Schwimmer and John Travolta. But if he does nab the statuette, it’d be richly deserved.

Woodbine’s performance is simultaneously understated and expansive; pacing his words, enunciating every crisp syllable, he effortlessly fills the room. The character of Milligan is a violent and dastardly man who is at peace with that fact: caught in a professional maelstrom, flanked by mute twin goons, he’s as calm as you like. Milligan moves as if every new bit of disaster has always somehow been a part of his plan.

It’s one of the strangest, most compelling TV characters in years. And that it’s the first time we’ve really paid attention to Woodbine in over a decade only makes it all the more strange. How, exactly, did Bokeem Woodbine end up saving his career in Fargo, North Dakota?

Courtesy of HBO

Courtesy of HBO

Growing up in Harlem, Woodbine had always loved two things: movies, and rock n’ roll. His favorite theater was a Loews on the Upper West Side, a quick ride down on the 1 train. “I wasn’t really thinking about studying forms,” he said on the phone from Atlanta. “It was purely whatever had my interest at the time. I would see something like The Last Emperor” — Bernardo Bertolucci’s epic 1987 Best Picture Winner — “and Gremlins” — 1984’s loopy horror-comedy — “and I would get different feelings. I used to go purely for the reason most people go: to be entertained, to escape.”

But the idea of an acting career was not something he entertained: “Not even in the slightest, man. Not even in the slightest.” The plan was music. He was a guitarist and a singer obsessed with the dinosaurs of ’70s cock-rock, in love with everything from Bad Brains to Guns N' Roses. Zeppelin kids in late ’80s Harlem weren’t exactly a dime a dozen, but Woodbine managed to find enough fellow travelers throughout the city to put together a few bands. He was going to be a rockstar.

He was never actually seen on screen in Juice: he ended up as a stand-in. Still, the film’s casting director asked for his contact information. “I remember feeling right then and there that maybe she was seeing something in me,” Woodbine recalled. “She wasn’t asking everybody [for phone numbers]. I thought, ‘Wow. Maybe something will happen.’” Ten minutes later, he forgot all about it. About a year and a half after his little brush with the movie business, completely out of the blue, he got a phone call.

The casting director’s name was Jaki Brown-Karman, and she’s something of a legend in the game. She was a key figure in the classic ’90s hood movie run (she discovered Cuba Gooding Jr. while casting for Boyz N The Hood); over the next few decades, she’d work with names like Quentin Tarantino, Ice Cube, and David Simon. Whatever Woodbine had flashed in his initial Juice audition intrigued her enough. Maybe it was his crooked grin. Or maybe it was the roiling spikes of intensity that seem to come to him easily.

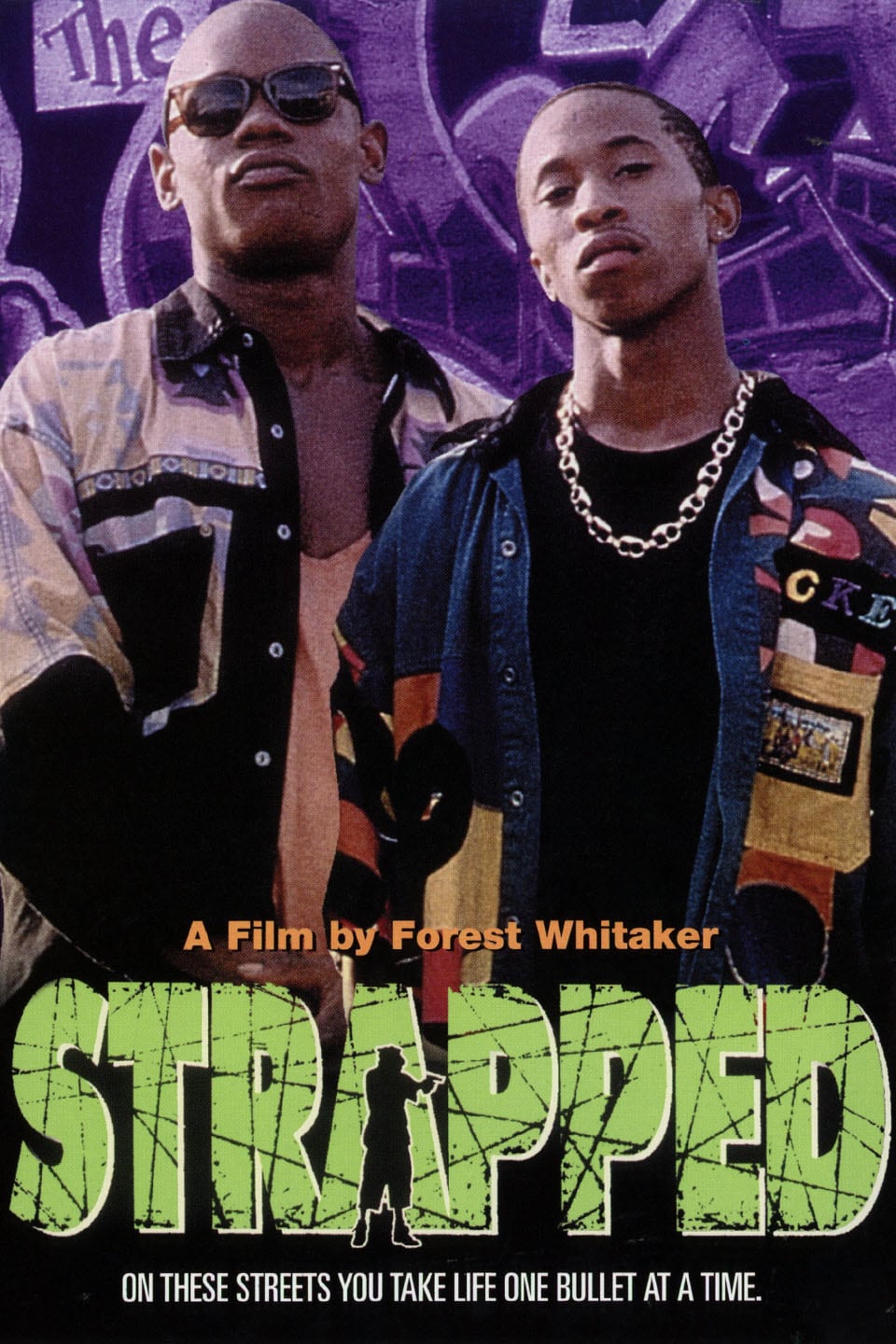

She called him in to a crowded casting office for her new project, an HBO TV movie called Strapped. It was a street morality tale in the vein of Boyz and Menace II Society. It was also a then 32-year-old Forest Whitaker’s directing debut. She handed him a script, told him to start reading; fifteen minutes later, she came back. “We went down a long hall,” Woodbine recalls, “and we opened the door and there was Forest. That was the first time I saw him.”

Just as Brown-Karman anticipated, Whitaker was taken with Woodbine. Auditions continued for a month: Woodbine remembers endlessly repeating his performance from that first day with producers and other unidentified decision-makers watching from the back of the room. “I’d always be like, ‘Who’s this guy?!’ And Forest would be like: ‘Don’t worry about it. Just do what you did last week.’” By the end of the month Woodbine was cast as Strapped's lead, Diquan, a troubled young man mixed up with the police.

Diquan’s sidekick, Bamboo, was played by Fredro Starr of the Queens rap duo Onyx. It was also Starr’s first real movie role, and the two newbies, embraced by Whitaker’s kindly directing style, began to bond. At the time Onyx was recording its 1993 debut Bacdafucup, and Woodbine would tag along to the famous Chung King Studios where Run-DMC, Beastie Boys, and LL Cool J have all worked. “He had the bald head and he kind of looked like Stick a little,” Starr said, referencing his Onyx partner (and fellow actor) Sticky Fingaz. “People thought he was part of Onyx!”

Though he was “hip hop literate,” Starr said, Woodbine was always on a different wave. “He would bring his guitar to set. For me, coming from the hood, you didn’t really see a lot of black guys doing the rock n’ roll thing.” Starr remembers Woodbine on set in between takes wearing big boots and tight pants with no underwear. “I was like, ‘Yo dawg, where your underwear?’ He like ‘Nah man — commando!’ That was Bokeem. That rock n’ roll mentality.”

Strapped premiered on HBO in the late summer of 1993, got some nice reviews, and then was mostly forgotten. But Woodbine’s career took off. His next project was Crooklyn with Spike Lee, who was fresh off directing the monumental Malcolm X. Then he did Jason’s Lyric, a tough romantic drama that eventually won cult status. That he’d never aspired to act seemed beside the point; he was excelling. “It started to feel naturally pretty early man,” he says now. “It started to feel like a place where I belonged pretty quickly.”

In 1996, just before the legend’s death, he acted in the video for Tupac’s “I Ain’t Mad At Cha.” On set, ‘Pac confided in Woodbine: he was planning to release a unity record featuring himself and fellow West Coast artists alongside Biggie, Mobb Deep, and other East Coast MCs. “He had a plan to put everybody together on one record and just squash the beef,” Woodbine said. “He wanted to take the power away from the labels that were exploiting the situation. It angered him that they were profiting; he wanted to stop the cash flow. It wasn’t something I was supposed to tell people about, you know what I’m saying? I honored that, and I just waited for that record to come out. But unfortunately, as you know, it never did.”

There was more good fortune and brushes with greatness. He went gritty in the Hughes Brothers’ anguished shoot-em-up Dead Presidents, and went goofy as a hitman who newly discovers masturbation in the big-budget comedy The Big Hit. And, of course, the money came in and “that part was incredible,” he said.

Woodbine remembers his first-ever chance to splurge: it was a store in the West Village, a hoity-toity kind of place. He walked in, started eyeing a black leather jacket, and had himself a little Pretty Woman moment. “I was trying it on and the [staff] was kind of obnoxious,” he said. “I was like ‘I’m gonna wear it out!’ and they were kind of like, ‘Yeah, sure.’ I took out $700 cash and put it on the table and said, ‘We good?’ That feeling …”

Woodbine was never the kind of star to have shopkeepers fawning over him. But for a lot of us throughout the nineties, his was a welcome and memorable presence. It was a little due to his peculiar name: it was a grand name, a name fit for the movies. It was a little more due his peculiar look: the nicely gap-toothed teeth, the big jutting ears. But more than anything it was him: he had an energy that could be pointed, seemingly, any direction he liked. Woodbine could be brash or sullen, wild-eyed or quietly calculating — one day a villain, the next a victim. Brown-Karman was right to pluck him out of obscurity because on screen, more often than not, he popped. And then suddenly, he was gone.

Courtesy Universal Pictures

Courtesy Universal Pictures

Courtesy TriStar Pictures

Courtesy TriStar Pictures

The freeze in Woodbine’s career came almost as suddenly as his accidental start, with no real explanation. There were no on-set meltdowns, no tabloid-worthy incidents, nothing dramatic to make Hollywood fall out of love. After a fertile decade came fallow times.

He never, ever stopped working, but the roles got smaller. He sustained his career on a diet of one-off guest appearances on unheralded TV (Blade: The Series) and C-list movies you’ve most likely never heard: Blood of A Champion, 18 Fingers of Death!, The Breed (the latter set, according to Wikipedia, in “a dystopic future in which vampires are a marginalized race living in formerly Jewish ghettos.”) He also started to specialize in those cheap cash-in sequels with no artistic link to their original film other than a producer who had connived their way into name rights. There was both Sniper 2, with Tom Berenger (who Woodbine loved working with: “he had wisdom tips!”) and Jarhead 2: Field of Fire.

“It was a lot of going to Eastern Europe,” Woodbine recalls, with an endearing self-awareness. “Which I love! But I mean, if you look at the location and it says Budapest or Bulgaria — it’s probably showing up at Cinemax at three in the morning. Yeaaaaah, this is not opening at Cannes. I had began to accept that maybe this was the beginning of the end.”

He doesn’t mean the end of his acting career: he was just well-known enough to not have to turn to waiting tables. But Woodbine understood that he’d “touched the mainstream for a second — for a half a second — and then I wasn’t resonating anymore with the people who make the mainstream decisions.” So the plan was to keep grinding it out. “You know, I still gotta eat. I thought, ‘I gotta be smart about my bread.’ But if I can keep this going for another 20, 30 years …”

So he shifted the focus from greater recognition to a renewed aim on quality. “I said ‘once I sign that contract, if my name is on that piece of paper — whether I’m crazy or not about the director or the script or the character — I’m gonna find a way to motivate myself.’ It was a recommitment to focus. Remembering the things that Forest had imparted to me, and what life had taught me. Getting knocked down and getting right back to it.”

Courtesy of FX

Courtesy of FX

The offer to audition for Fargo came in 2014. It was a bigger opportunity than he’d seen in a long time. Woodbine reacted by sequestering himself in his California home for three days prepping for his audition, taking breaks only to watch old Jackie Chan movies — Snakes In The Eagle’s Shadow, The Fearless Hyena — “for inspiration.”

“The whole time I’m thinking that any given moment I might get a call saying it was a misunderstanding, it was a mistake,” Woodbine said. “It was like, ‘Let’s hurry up and get into the audition before they realize what they’ve done.’ I just wanted it so bad, you know?”

That little disconnect from reality is what led him to land on the particular choice he made for the character of Mike Milligan. “The first thing that came into my mind was this ethereal surrealism,” he said. “It was like an epiphany. I started reading it in that voice.” That voice is a kind of cheeky self-aware flat-affect, like a very clever, very self-possessed man who’s recently suffered a serious but ultimately non-traumatic head injury. “What could be more outlandish? What could be more out there? I heard it and went with it and kept going.”

Just over 20 years ago, in the audition rooms of Juice and Strapped, Woodbine had stumbled into a career. Decades later, in another audition room, he rebirthed one. Says Fargo’s creator Noah Hawley, “Bokeem's take was a mixture of soft and hard edges. He brought a unique cadence to the words and understood just where the comedy and menace collided.” Hawley knew of Woodbine’s work but “it was his performance in that room and the way that he interpreted the material — personalized it — that won him the role.”

“You know, my wife says I fainted,” Bokeem remembers of the moment he got the call that he’d landed the part. “I didn’t faint. I was standing by the refrigerator and I kind of leaned against it slightly. Slightly. I stress the word ‘slightly.’ But she started jumping up and down. The whole family was jumping up and down.” He paused to let out a dry slow chuckle. “It was pretty silly, man.”

Their joy was prophetic. Almost immediately, Fargo and Mike Milligan started making waves for Woodbine. “Even before it finished airing, the phone was ringing,” Woodbine said. “Before it finished airing! And it hasn’t stopped. It’s still ringing.”

Winning the Emmy would be great, he said, but practically speaking, the damage has been done. We spoke as Woodbine was in Atlanta shooting the new Spider-Man movie. He can’t really talk about it, but set leaks indicate Woodbine is playing one of the main villains, the nefarious Herman Schultz, a.k.a Shocker. It’s hard to know what happens next, but it will likely be a while now before Woodbine gets back to the once-familiar confines of Eastern Europe. “It’s night and day,” Woodbine said. “I’ll measure everything that I do in my career from here on out as before Fargo and after Fargo.”