Niklas Halle'n

/

Getty Images

Niklas Halle'n

/

Getty Images

Last weekend I hung out with my parents and, because it is near-fall and the busy holiday season is approaching, my mother gave me a list of family events to put in my schedule: Navratri, a nine-night celebration of the goddess Durga, is the first week of October; Diwali, the Hindu new year, falls a few weeks later, on Halloween. As a kid, I’d be gifted new outfits to wear to the mandir or to dance garba because it was one of the few opportunities to wear traditional clothing. These were often gauzy and gaudy, pretty little girl outfits; chaniya cholis in bright, garish colors, offset with gold lamé paneling and bold prints. I had more choice in the matter as a teen: one year I was very into my mom’s printed chiffon ‘vintage’ saris. The next, I obsessed over the bandhani tie-dye pattern native to my family’s home state of Gujarat. And the following year, all the high school girls paired saris with tank tops instead of hand-sewn, matching blouses. Dressing up in traditional clothing was (and still largely is) a gendered experience: my dad and brother, wearing jeans or slacks and polo shirts, would watch TV and wait as my mom and I headed upstairs to dress, a full two hours before piling into the minivan.

I don’t live at home anymore so these moments are largely absent from my life — unless there’s a family wedding. Even when joining my parents at their mandir, I might only sometimes wear a salwar.

So I was both nostalgia-struck and impressed by the referential breadth of Indian-British designer Ashish Gupta’s Spring 2017 London Fashion Week presentation, Bollywood Bloodbath. The chaniya cholis of my childhood were there in the first look; a round, floral-printed skirt, in a porny shade of red, worn by British model Neelam Gill with a graphic tee. Delhi-born, London-based Ashish is an expressly cheeky designer who has collaborated with Topshop for years, dressed M.I.A., and is renowned for festooning his shit with sequins. Sparkle was still evident — this time on pastel, almost-dowdy skirt suits that reminded me of the Trini and Guyanese grandmothers in my parents’ congregation — but for SS2017, Ashish’s references went beyond the easy camp of Bollywood. It was specific to distinct, diverse elements of South Asian tradition and diaspora, spanning pop culture and folk art. There were alta-stained hands and feet (a powdered dye that stains, like henna) and thick braid extensions entwined with jasmine-and-mini rose garlands, adornment common to bharatnatyam dancers, but also Bengali women, and Tamil brides. I tweeted out a few pictures with the caption "casual mandir looks,” because they conjured a world of easy, go-between style — sometimes formal, sometimes matchy-matchy, sometimes haphazard — that felt appropriate for what worship looks like to me, skimpiness and all. The apex of this is the floral and paisley-embellished denim kurti and patiala set that I need so I can swag out on the new year.

This sexy and nostalgic collection is catnip for people who are more diasporic than Desi.

Niklas Halle'n

/

Getty Images

Niklas Halle'n

/

Getty Images

Tim P. Whitby

/

Getty Images

Tim P. Whitby

/

Getty Images

Niklas Halle'n

/

Getty Images

Niklas Halle'n

/

Getty Images

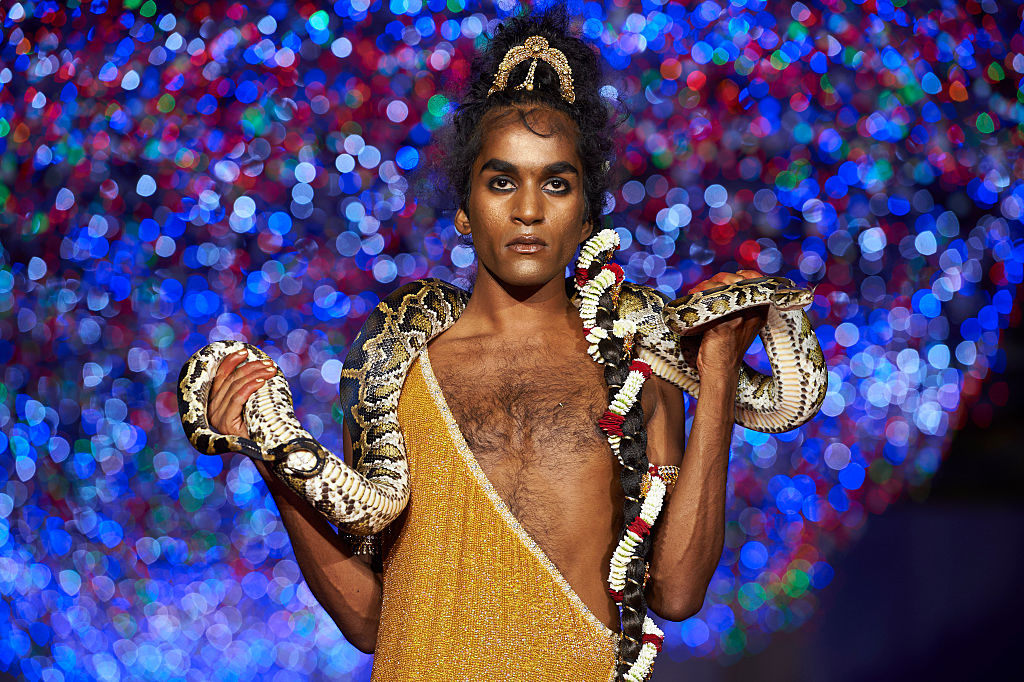

Ashish’s specific context for this show was Brexit and perhaps the “anti-difference” fearmongering behind the vote is why the multicultural models, some carrying individually-wrapped roses like street vendors, had tears streaming down their faces? It’s an earnest expression of how migration can be a catalyst for imagination. But because the designer grew up in Delhi, where his production is still based, I’d also hope that the irreverent, gender-nonplussed, portentously sacrilegious execution of Bollywood Bloodbath was a thumbed nose at the constantly rising religious fundamentalism and cultural conservatism in India (and spreading to the diaspora) via right-wing politicians like Prime Minister Narendra Modi. I’m thinking about the explicitly Hindu references like models with tikkas decorating their foreheads, wearing toy crowns trailed by sheer dupattas in baby pink and fluorescent lilac. This latter choice feels like a specific reference to the camp of serialized depictions of Hindu texts, like Ramayan or Mahabarat, an effect dutifully replicated by stage aunties in the religious plays I participated in as a kid. There was also the male model in a chest-baring mustard slip dress with a snake around his neck and gunghroo on his ankles, as well as blue and yellow face paint in homage to deities like Krishna and Kali, but also kathakali, a South Indian theater style that was historically performed by all-male ensembles. Mixing religious iconography and ephemera with progressive contemporary social norms feels like a pointed throwback to primeval, pre-colonial South Asia — there is a documented history of transgenderism and sexual openness — while also ratcheting up diversity points for Ashish’s audience of white, wealthy, fashion liberals.

A first-generation westerner like me might see Ashish’s success as a boon for brown people but we certainly aren’t his primary consumer base. (The pushback to sparkly Afro wigs worn by models at his FW2016 show certainly speaks to this, as well as the ways in which South Asians contribute to racism in mass culture). But this new, sexy and nostalgic collection is catnip for people who are more diasporic than Desi, emboldened by the successes of mainstream-browns like Mindy Kaling, Aziz Ansari, and Priyanka Chopra. We are obviously ready for this injection of easy-consumption “exotic India” into institutions like London Fashion Week. But as fashion retail is unmoored from Paris, London, and New York City, I wonder what will be the repercussions of the diaspora (privileged by class and language, if not merely geography) translating national culture through these runways? By invoking sartorial and adornment traditions from across South Asia and its satellite communities, Bollywood Bloodbath is a more even expression of what Indian culture is, beyond the traditionally north Indian, Hindi-speaking, fair-skinned-filmi interpretation that dominates in the west. That’s to say, it reminds me of just how foreign an Indian I am.