Keith Dube

RDF Television

Keith Dube

RDF Television

If you are a black man in Britain, you are 17 times more likely to be diagnosed with a serious mental health condition and six times more likely than a white man to be an inpatient in a mental health unit. These statistics alone are shocking; but what's more, these problems are often suffered in silence. According to U.K. charity Time To Change, 80% of POC who have experienced both mental health illnesses and discrimination are “unable to speak about about their experiences.” Without hearing about these experiences, many don't see how mental health issues can impact on the day-to-day lives of black men and women.

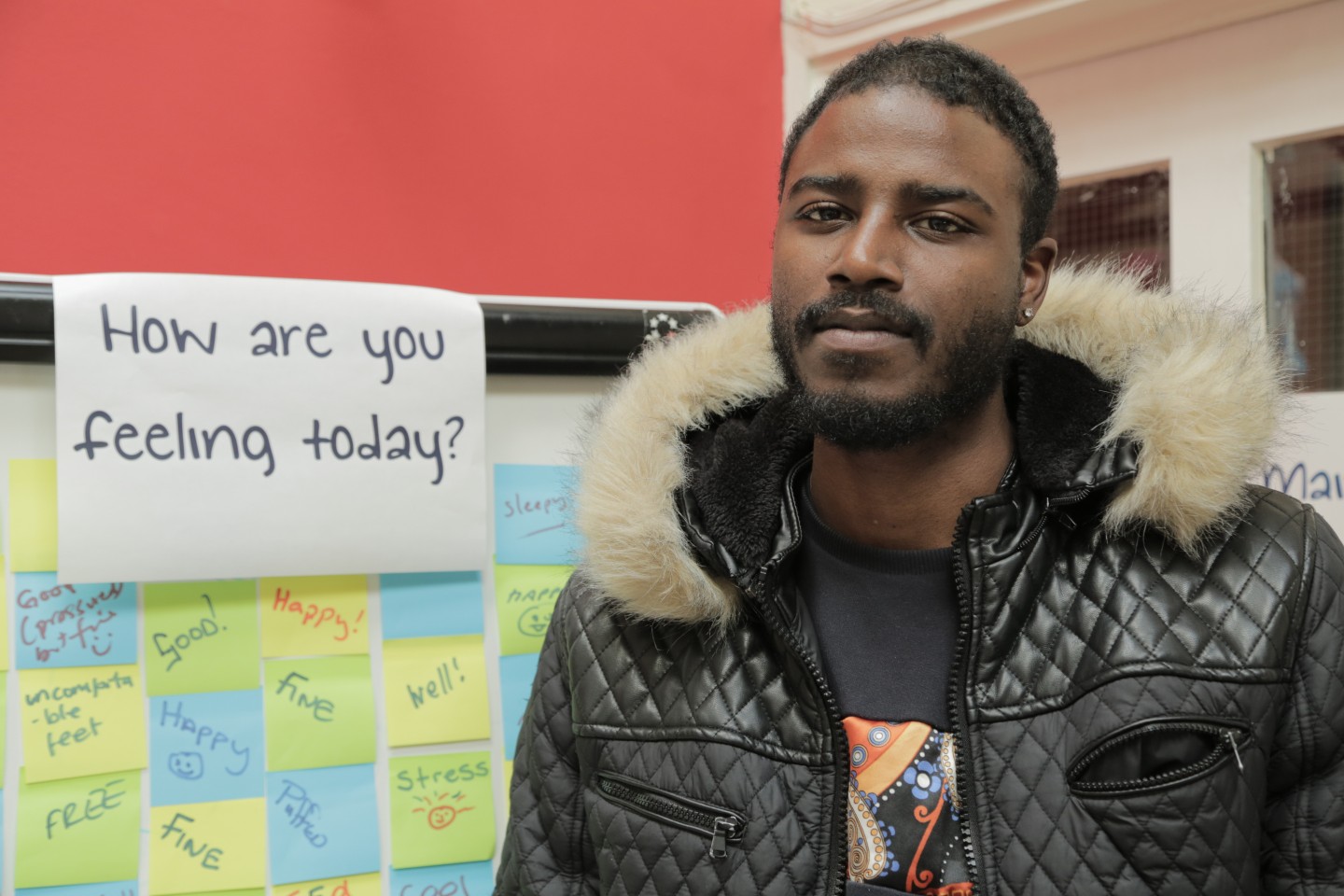

This is what Zimbabwe-born, London-based writer and presenter (of online London station Radar Radio's breakfast show) Keith Dube sets out to uncover in a new documentary. Launching September 27 [update: available here] on the BBC's younger, cooler online channel BBC Three, Being Black, Going Crazy? shows 26-year-old Dube meeting black people suffering a range of problems, including anxiety, depression, and psychosis. The program aims to sensitively bring attention to the mental health crisis ongoing in black, British communities.

Dube’s interest in mental health is borne from his own experiences; three or four years ago, he was diagnosed with depression. Thankfully, he was referred to a therapist through the NHS, and today says he's doing much better. In February 2016, he published a self-help book (Kind Of Like A Self Help Book) which touches on his criminal past, the fall into poverty which triggered his depression, and how he managed to get through his darkest times. With all this behind him, Dube’s immediate empathy with the subjects of the documentary shines through its scenes. In a long phone conversation with The FADER, he was just as willing to be open and honest.

KEITH DUBE: When I moved to London [at 18] I got into a few things that I shouldn’t have been getting into, which led to my struggles with mental health. I had a decent childhood, but my relationship with my dad was difficult. We lived together but we didn’t really know each other. I was trying to find my sense of family elsewhere. I was doing criminal shit. Later, I started selling drugs for a little bit. I was the worst drug dealer in the world. I nearly got killed over £300, and that’s when I decided to give up and get my life together. I went to my doctor and I told him, I’ve been going through some shit. When I’m supposed to be happy, I’m not happy. I’m constantly down, I don’t want to leave my house. My motivation levels were at zero. I’d lost so much weight. I’d reached a point where something had to give.

[At first] the doctor prescribed medication without really understanding my problems. It was like, Wow, you don’t even know what’s going on with me. I told him I was in pain, and we had spoken about what was bugging me, but he was too quick to just throw medicine at me. I wanted to deal with what was going on in my life. The doctor then recommended me to a therapist that changed my life, essentially. It’s what I needed at the time.

Keith Dube

RDF Television

Keith Dube

RDF Television

“When it comes to mental health, there’s often a lack of understanding. It’s trying to treat an African problem with a white person’s manual. We are very different.”

I moved to Australia in 2014 and wrote my book. I wanted to write something [about mental health] that my friends could relate to, something that wasn’t written by a white man in some big building in America somewhere. Over the years, I’ve found out about my triggers and learned how to deal with different things. When I moved back to London this year, I was ready to take everything on. I first spoke about the black mental health angle with the production company I worked with, and I was lucky enough to be able to present the film.

We started filming the documentary in April, and finished up about a month ago. I was definitely scared, because I knew I would be around a lot of people going through difficulties for a prolonged period of time. I had a psychologist that I could call on at any time thanks to the BBC.

Reading the statistics about black people and mental health was shocking. I wanted to find out why this was happening in our community. When we saw the numbers, I thought it was outright racism. But, as we went on, we discovered a lot of black people report their issues a whole lot later. If me and you go through mental health issues at the same age, but you report your issues at 12 and I wait until I’m 28 to report mine, our problems are at different stages — mine will be a lot further gone, because you’ve started dealing with yours earlier. It’s not even that we have worse mental health issues, it’s because of the taboo in the community. Most people don't talk about it. Their issues fester, and that’s how it leads to problems like sectioning.

Ashley Weir

RDF Television

Ashley Weir

RDF Television

“Everyone’s afraid to talk about it. We need to do something about it.”

When it comes to mental health, there's often a lack of understanding. It’s trying to treat an African problem with a white person’s manual. We are very different. In the film, I pressed on the idea of focusing on religion, because I’ve seen the situation where a lot of African churches will push people away from [medical] help. They’ll tell people, “Pray, pray, pray." But I think to myself, You can’t pray away schizophrenia. This person might have bipolar [disorder]. They might need medication. Don’t get me wrong, I know that people need prayer too — but there should be a balance.

Some people are from parts of Africa where aspects of mental health are looked at as witchcraft and they’re told that the witches have got them. So, they come over to this country and their doctor is evaluating them, and they start talking about the witches and the spirits. And the doctor's looking at them like, “Okay, something’s wrong.” All the doctor heard was “witches and spirits,” and as far as they're concerned, the person has a problem. But where they come from, that’s literally what they’ve been told is true.

I just think awareness has to be raised. Everyone’s afraid to talk about it. I spoke to a girl the other day, and whenever people ask her about her family, she lies, because her mum has mental health issues. People have made her feel embarrassed about what her mum’s going through. We need to do something about it, because you wouldn’t be embarrassed about saying, “My mum has cancer.” If you don’t speak about it, it could get worse.