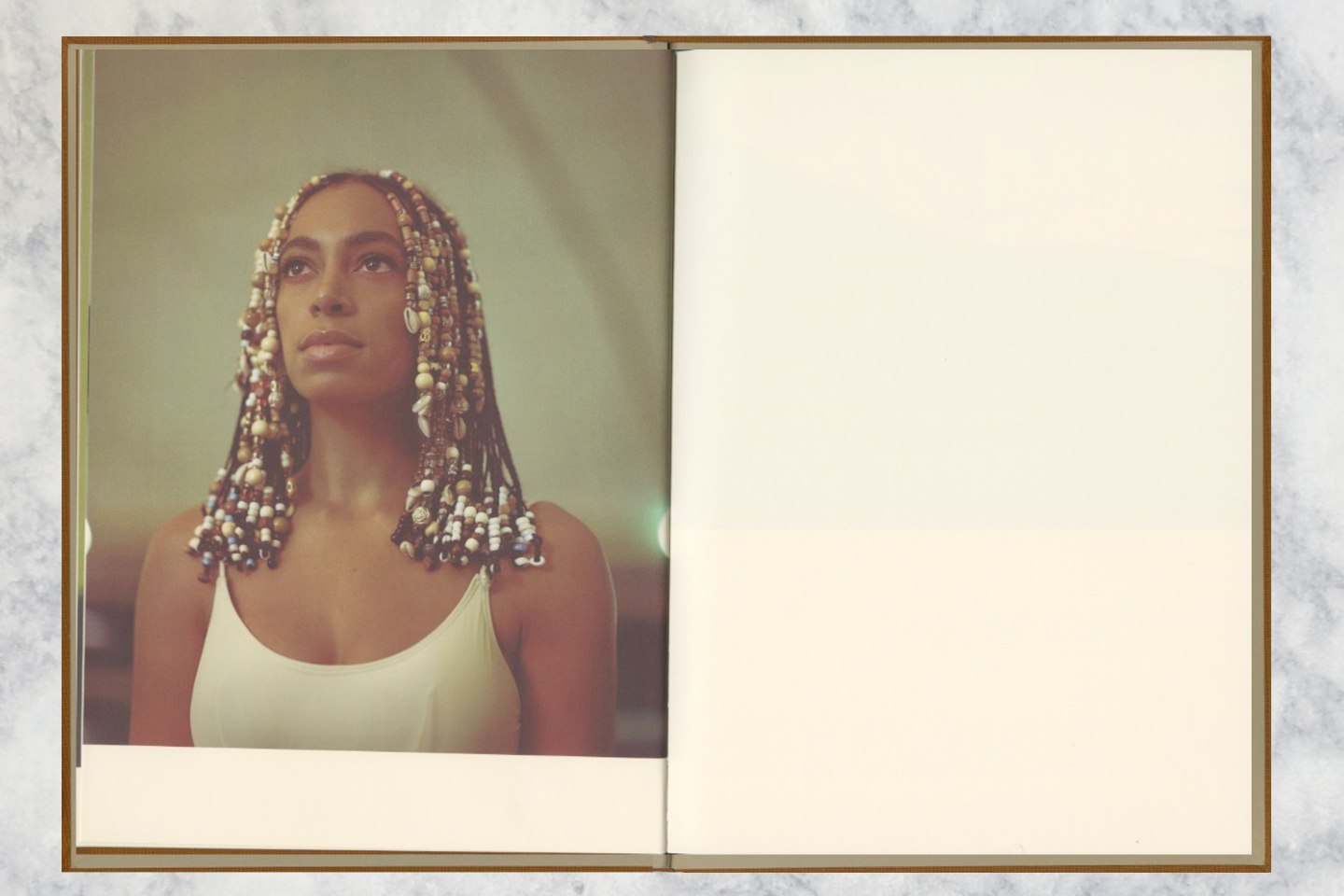

Courtesy of Columbia Records

Courtesy of Columbia Records

On Friday, Solange Knowles released her third studio album, A Seat at the Table. The 21-track record is part personal memoir, part cultural analysis, and, thoroughly, a remedy for the intergenerational traumas of her own past and of America's, all explored through a four-year recording process. A Seat at the Table expresses the brunt of this pain — anger, sadness, cynicism. But with the help of friends and collaborators like Lil Wayne, The-Dream, Kelela, and an American tycoon, Master P, it plays with a tenderness that, as Solange explained to The FADER, might help others heal, too.

How much of this album was made with the intention of radiating a healing vibe outward?

I feel like, in some ways, the album wrote itself. When I first started to write a lot of new songs, it was just me and piano. And [the songs] didn’t have life; they were just the beginning stages. Throughout the different eras of the album, I found my voice and it became clearer and clearer through the backdrop of what was happening in the world and everyday life. Lyrically, everything that came to me on this record was directly influenced by my personal journey, but also the journey of so many people around me. That’s why I feel like it wrote itself.

In my process, I typically start with a melody. I freestyle a melody, and I build harmonies on melodies, which is kind of ass-backwards [laughs] because then I have to do them over again when I fill them with words. The actual lyric writing of the album is tricky when you’re so sold to a melody. The little nuances and syllables and things that you’re saying might sound one way, and when you fill in the lyrics, it changes the essence of it. [But] I allowed myself to have that space, because I didn’t want to force myself to write anything that didn’t truly come from the soul.

One of your inspirations for this record was Claudia Rankine’s 2014 book, Citizen: An American Lyric. How did it help you through the writing process?

I was actually homeschooled from eighth grade, and I didn’t go to college. I learned to be a student through the world and through my experiences, through traveling, and meeting people. Sometimes I didn’t necessarily have the language to express myself. I knew I had all of these intense feelings and opinions on things, but i didn’t have the language. Constantly reading and trying to challenge the way I articulated things was a huge part of the writing process of this album. Claudia was someone who directly inspired my writing because her poetry cuts through in a really unique way. She leaves certain things up for your interpretation, while also being very direct. I identified with that so much. That has always been something, in terms of my songwriting, that I’ve strived for. I want people to have a personalized experience, but I want my role to be clear within that. Citizen just so powerfully expressed many things I’d been feeling that I just thought, Oh wow, okay. I can actually name these incidents in a very personal way. And I think that, in the past, I might have been a bit more reluctant in my songwriting to be so clear in the narrative — I use a lot of analogies, and I try to have a certain sense of poetry in my writing — but I feel like she really helped inspire me to be more direct in my feelings.

How did you find that book?

My husband and I travel to Marfa, [Texas] pretty frequently. We became friends with a guy who owns a bookstore there, and he always recommended books that he thought that I would be into. So we went to Marfa for our first year anniversary and we had an Airbnb, and at midnight we blasted “I’m In Love” by The Gap Band. We had a joint. And out of nowhere the police started banging on the door of our Airbnb. It’s a small town so word got around, and our friend reached out and said, "I think you need to read this book. I think it would be good for you." I’m super thankful for that. From there I started to read some of her past work. She’s a friend of a friend, so she knows that I’m a huge fan.

Courtesy of Columbia Records

Courtesy of Columbia Records

Did you think at all about the timing of this release?

True was such an independent project. No one was expecting it so I based my release off of when the [“Losing You”] video would be done. Because I didn’t have a major label system where you wait for clearances, it was just like, "Okay it’s ready now, it can go through TuneCore, and I’m just gonna put it out.: There was so much gratification in the idea of when something is ready, it’s ready.

The record industry obviously has thoughts on why you need to promote and have a campaign, but honestly — after feeling the gratification of it really being about the music — I’d just been working on this project for so long it was like, The minute it’s mixed and mastered, it has to come out. There were times throughout the last year [when] certain tragic incidents, horrific things happened, and I would like… I would hope that this record could provide a voice to cope through some of those times, but it just wasn’t ready.

What was the turning point?

Once I had these ideas of someone who really, really exhibited black empowerment and independence. I couldn’t think of anyone who was more fitting than Master P. He’s someone I’ve always had a great deal of admiration for. I asked him to come in and speak for this one song, and he ended up being the most incredible storyteller. We ended up talking for an hour and a half, two hours. It was so natural and it was, literally, like being in a self-help seminar. I was so exhausted and tired of the album-making process. Admittedly, at some points, I had run out of resources to finish everything.

What kind of resources?

Well, just money to make the album. I’d been working on it for so long and things add up. There’s a real reality in the process of album-making. You still have to generate income to support your family, so I’d been performing and DJing and curating and doing things to support and provide. At the tail end of it I was really tired. I had about 30 songs that I had written, and I was trying to, at that point, reduce them to 15, and then to 10. That was what I imagined the album would be. After Master P came in and talked, me and my boy Troy — who I’ve worked with since I was 15 — we looked at each other and were like, "Wait a minute, this is a much much bigger story than the album." Although I wanted the album to have those moments of grief, and being able to be angry and express rage, and trying to figure out how to cope in those moments. I also wanted it to make people feel empowered and [that] in the midst of all of this we can still dream, and uplift, and laugh like we always have. I feel like Master P perfectly encompassed that in our talk together. He was the link for me in terms of connectivity to that empowerment and regality. That is something I really, really wanted to express. We, as black people, have historically not been presented as regal beings in society. I feel like if there is anyone who has expressed that from day one, it’s been Master P. He’s always been so, so incredibly regal, even in the way he expressed through his wealth — all of the gold, but also the wealth of independence.

My dad was a manager and he was such a student of black people of power within the music industry. I heard him talking about all these paths and roads that people took, and where he felt someone took a wrong turn, or maybe they shouldn’t have sold this, or whatever — that was the chatter in my upbringing. And I remember him always talking about Master P with a sense of admiration and love and respect. I see so much of my father in Master P. My dad didn’t use the trunk system [to sell CDs directly to fans], but he started in the living room of our house and went from label to label on foot, and wrote letters. He did not have a clue as to what the music industry was until he embarked on it, and people had a great deal of respect for him because of how he represented himself and his family. I think that it was really healing for me to hear Master P tell those stories. He’s affirming that we can build and create opportunities for ourselves: we don’t have to ask for permission. He saw a vision within his neighborhood; being an Avon Lady and being Master P had a demand within our block.

I’m also thinking of the way you stood up for Brandy... Do you feel a personal responsibility in mythologizing these black cultural creators?

It’s mindblowing to me that someone wouldn’t give Brandy or Master P credit in all that they have done and established in our culture! I don’t think I’m unconsciously thinking in that way. I’m thinking about how “Hoody Hoo” makes me feel and how, in some of my darkest moments, music has saved me. Since I was a little girl, I was reading all of the album credits, and every interview. I was just a real R&B and hip-hop music stan. I feel like I am a fan almost more than a musician sometimes! And I feel very protective; these are my heroes.

Courtesy of Columbia Records

Courtesy of Columbia Records

“I had to make this album to become a better me, but also a better mother.”

Do musicians have a responsibility to speak on social issues?

That’s a very complex question. When I interviewed Amandla [Stenberg] for Teen Vogue she said something like, "We’re all activists, even in just existing." I think that I always knew that but I started to channel my ideas of activism very differently. I don’t think it’s everyone’s responsibility if it’s not in their will. But I do feel conflicted when people feel like they may not have that calling, but they speak out against the movement. That, to me, is very problematic. I’d almost rather you just not speak at all. It is very painful. All that I ask is that people are sensitive to others' truths, even if it’s not their own. I don’t think everyone needs to be out here with pickets and signs and protesting; maybe their form of that is going into their office every day and standing firm as a person of color. We just have to be sensitive to each other and not criticize people as much as we do because their truth isn’t our truth, or they aren’t in the same place on the journey as we are — that’s kind of irresponsible.

You’ve spoken about some of the things you learned about your heritage and music in making this record. And a big public conversation right now is how black parents speak to their kids, especially young boys, about how to move in the world. How do you engage your son in learning about identity, in things that aren't just about trauma and fear?

I have learned so, so much in the past few years. That is the beauty of internet culture — it's having so many resources that you can instantly experience, dwell on, live with, and challenge yourself. I am a much better me because of that. I had to make this album to become a better me, but also a better mother. I couldn't carry everything and give my son the most undivided attention and love and nurturing as I was working through these battles. Something a lot of people don't realize is when you have to work through some of these traumas and challenges with yourself, and you're having to take care of another human being and make sure that they feel protected and aren't carrying any of that weight... I think that's why it was so important to have my father speak about his past traumas and creating the connectivity of how it gets passed on from generation to generation, and the way a lot of things are just not changing.

I feel like I'm more equipped now, through working that stuff out through my art and not bringing it home, and making sure that our home is a safe place filled with love and nurturing and a sense of lightness. That is the biggest blessing of this album: that I was able to channel that through my work and not bring it home. I want my son to be able to exist in this world without all of those burdens. I want him to be smart and aware, and I want him to be equipped. I don't want him to carry the burden and pass on the traumas that exist when you're existing here.

Do you see A Seat at the Table and your sister’s album, LEMONADE, as companion records in any specific way?

We have the same mother and the same father. We grew up in the same household, and so we had and heard the same conversations. One of the joys in your mom being an Instagram star is that people are, I think, starting to understand the environment that we grew up in. Through her voice and organizing, and her really being an advocate for black equality — and obviously through the intro of "Don't Touch My Hair" — people are a little clearer in terms of the upbringing that we had and us having these very politically-charged, socially-charged conversations on a daily basis. It shouldn't be surprising that two people who grew up in the same household with the same parents who are very, very aware — just like everyone else is — of all of the inequalities and the pain and suffering of our people right now, would create art that reflects that.

I'm really proud of my sister and I'm really proud of her record and her work and I've always been. As far as I'm concerned, she's always been an activist from the beginning of her career and she's always been very, very black. My sister has always been a voice for black people and black empowerment. And I give so much of that credit to my parents. My dad had a really, really, really hell of a tough time growing up. He integrated both his junior high school and his elementary school, and he also decided in the midst of that — outside of them spitting on him and hosing him down and tasering him and all of the horrific things that he went through — that he was still going to stand for equality. He participated in sit-ins, he marched, he was hosed down. He was a part of the Civil Rights movement. And I don't think that there's any way for your parents to go through of all that, and you not have a certain level of sensitivity and consciousness to what's happening around you and wanting to use your voice to reflect that.

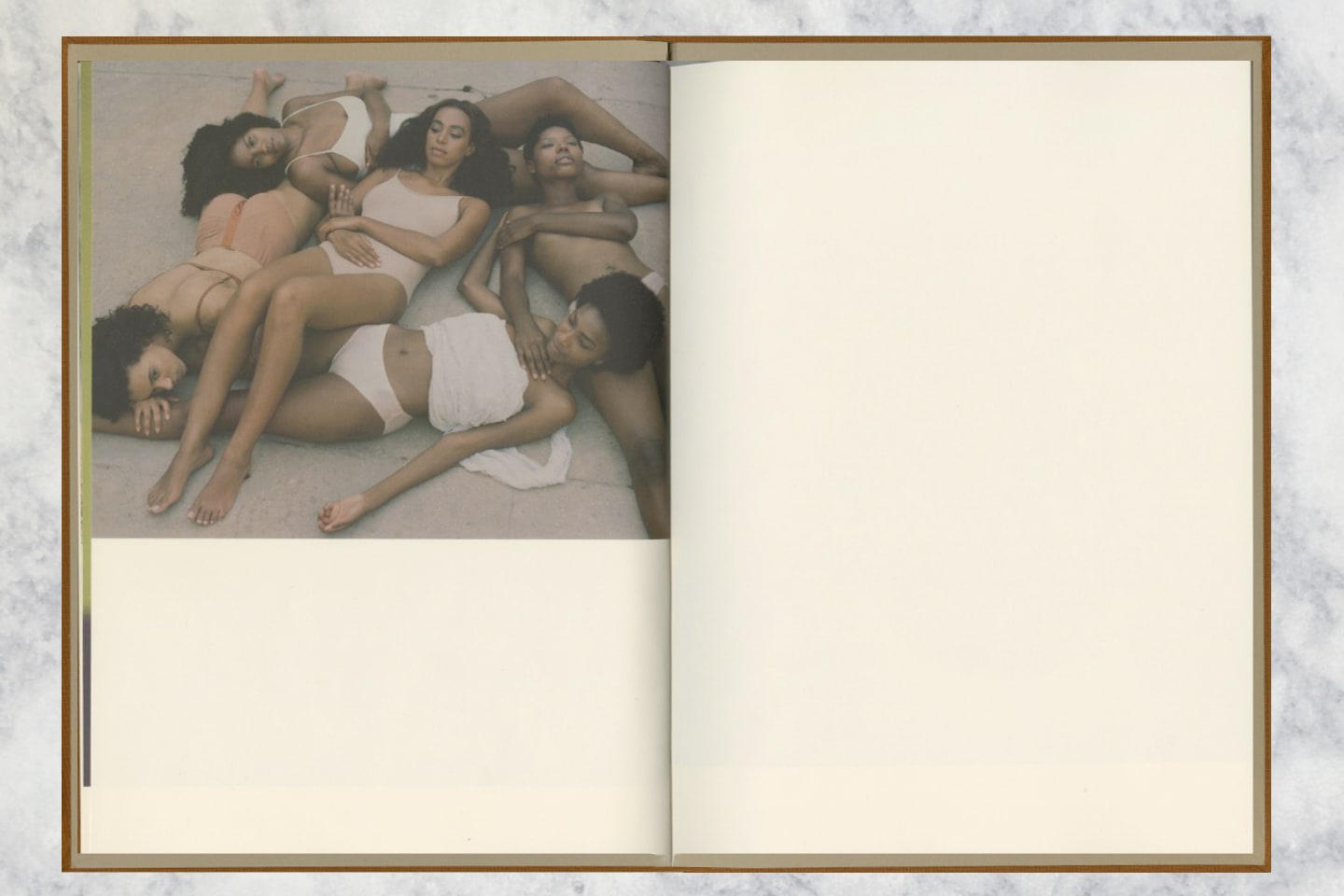

Courtesy of Columbia Records

Courtesy of Columbia Records

“I wanted the album to have those moments of grief, and being able to be angry and express rage, and trying to figure out how to cope in those moments. I also wanted it to make people feel empowered and [that] in the midst of all of this we can still dream, and uplift, and laugh like we always have.”

Do you identify with the term “carefree” in the context of “carefree black girl/boy”?

In one sense, it's incredibly difficult that we even have to come up with the term "black joy," to identify that as a state of mind. We should just be able to exist whenever and however we please and choose to. But I also understand the power of manifesting something when you speak it into existence, and almost needing to give it a name to show people, "Hey, this is how we see ourselves and this is how we want you to see us." There are a lot of moments in my life where I have a lot of care. I have a lot of things to think about and a lot of things that I'm managing and trying to navigate through. And then there are some moments when I feel free as fuck, and I feel completely weightless and at peace. Those are both the complexities of being a woman of color, and I celebrate both of those. They are both who I am and they need each other to exist.

Visually and musically you're chronicling a black American experience, that obviously has roots in Africa. How much are you thinking about blackness outside of an American context?

Growing up we were always shown that that's where we were from. And my mother surrounded us with African art and positive African imagery and also put us in summer camps that spent a great deal of time celebrating the diaspora and connecting those dots. And I think that I had an awakening when I started to travel there — not for work or shows, just to go. I started to feel like, Why am I paying all this money and setting up all these vacations to go to Europe or some island? Like, why am I not going to Africa when I get a break? I spent time in Rwanda and Senegal and Ghana. And South Africa — Capetown and Joburg. Every time I had a break I'd bring Julez with me, and we'd just exist there. We met and connected with incredible people there and I think that it was really important for me to always accentuate and highlight that part of myself, and my history, and my journey because it's who I am and it's where I came from. I love feeling connected to that, it has helped me to understand myself more.

There’s something amazing about getting off the plane in a place where everyone looks like you!

[Laughs] Exactly, and I gotta say that’s a huge part of why I love living in New Orleans. It is a black community. I am surrounded by so much love, and pride, and blackness. It’s not escapable — it’s everywhere, and that feels very safe, and it feels great to constantly have those reinforcements.

I was a bit nervous about doing this interview. I’m obviously flattered you remembered the review I wrote about your Saint Heron compilation years ago, but in the back of my mind — thinking of the track “F.U.B.U.” that’s on this record — I hesitated knowing that as an Indian woman I'm not that “us” you’re talking about.

There’s a longer answer here in that you are a woman of color. It’s super important for all people of color to become allies and build on all of our inequalities. Obviously, our experiences as black women are super exclusive to us, as they might be to people of other backgrounds. But that’s something I’m really awakening to: the power of coming together as brown people and building. Throughout these last couple of years, I have been challenging myself to look at some parts of our struggles on a more global scale.

The other part is that I feel like with the album if there is anyone who is uncomfortable with my evolution and journey and voice, they probably weren’t here for the ride anyway. I certainly feel allowed to occupy this space right now and tell my truth and stand firm in it, whether it’s messy, or painful, or complicated. Some of my favorite artists have had those moments where they may have lost some folks along the way. I think about Lauryn’s Unplugged album and how many people must have stepped back — not must have, they did — when she existed in her truth, because maybe they couldn’t relate, or it felt too heavy. And I think about Nina Simone and that being the thread in her career, and her having to lose some people along the way. I got a long way before I can ever utter a syllable of my name next to those two greats [laughs]. I felt so much solace in knowing that it’s okay if everyone doesn’t come along for the journey at every point. And it’s unrealistic to expect people to.

There have been some people who feel like, "OK, you said it all in your work so maybe you shouldn’t do interviews." And there are some people who are like, "Use this to have these conversations and open a door to reach truth." Not to be cheesy but like, you know, pull up a chair and have a seat at the table and let’s really have these moments. I don’t really know, a day [into the release], where I stand in that. I feel a bit of both, but I feel very justified in being able to exhibit my truth in all spaces and all forms, and I’m not afraid of that. There was a time I was afraid of it. I’m raising an 11-year-old black kid in America and Trump is running for president, so if I’m going to be afraid of anything, I’m going to be afraid of that. And it’s going to make me want to continue to be as vocal about my truth and my experiences as I can be.