L-R: Al Bello, Mitchell Leff, Elsa

/

Getty Images

L-R: Al Bello, Mitchell Leff, Elsa

/

Getty Images

I live in New York, where a synapse-firing array of regional cuisines is always a subway ride away. You want really good Uyghur food as traditionally prepared by the Turkic Muslims of China’s Northwest? We can go do that. I work at The FADER, a music magazine guided in large part by its respect and curiosity toward cultures everywhere. I believe in multiculturalism, the notion that a society is strengthened by its interwoven cultures. I believe that America is the greatest argument for multiculturalism in the history of the world. Which makes being alive, right now, pretty goddamn stressful. Because these are fraught times for multiculturalism.

In July of 2016, the U.K. voted to leave the European Union. In the fall, Trump won the U.S. presidential election. Both events were fueled, in part, by voters’ desire for cultural revanchism. “Neither Brexit nor Trump are likely to bring great benefits to these voters,” the Times Magazine wrote in November. “But at least for a while, they can dream of taking their countries back to an imaginary, purer, more wholesome past.” Note “imaginary.” And after “wholesome,” add “white.”

Trump’s fight against multiculturalism will be expansive and hard to pin down. It’ll range from the explicitly racist — Trump’s pick for National Security Adviser is a hardliner who’s called Islam a “malignant cancer” — to the subtler. Obama made respectful celebrations of diverse religious and cultural practices a staple of his White House. When Trump wanted to honor Cinco de Mayo, he got a fucking taco bowl from his own shitty restaurant. The implicit end result for Trump’s America is in many ways already happening: the same immigrants that once made this country great will be unable, or unwilling, to come.

Watching hoops recently, though, I realized something. In the era of Trump, multiculturalism will have a powerful corporate ally: the NBA. Because while Trump fights against it, the league exhibits its splendors. It hasn’t been planned, or even much discussed. It’s just a natural byproduct of the talent on hand.

Vince Bucci

/

Getty Images

Vince Bucci

/

Getty Images

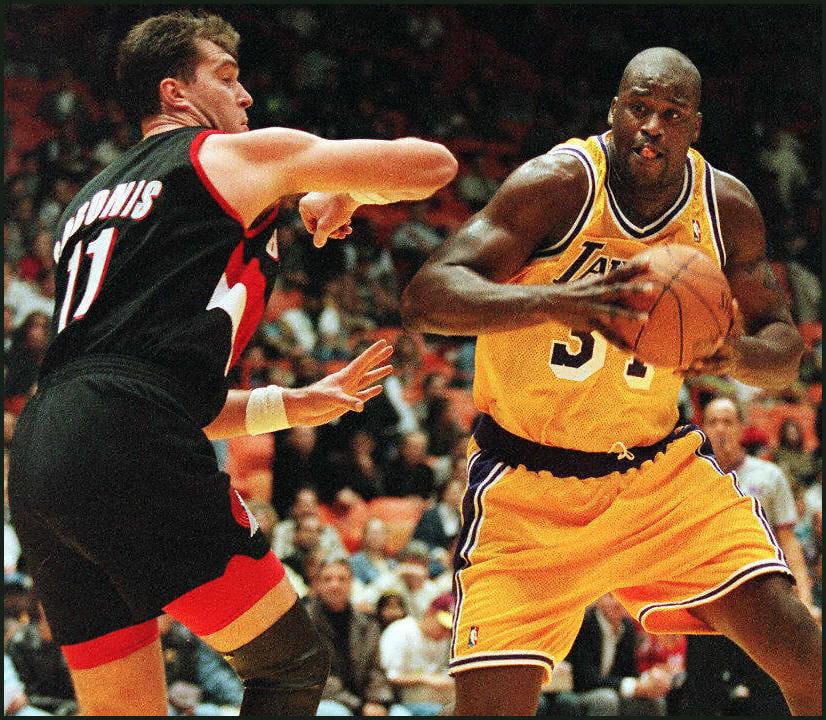

Non-Americans first began finding a regular home in the NBA in the early ’90s. The earliest waves were mostly from Eastern Europe. Some were long-distance bombers with preternatural touch; some were aging wizards who still saw passing lanes in 4-D. Non-Americans (mostly the Europeans) were stereotyped at first as “soft,” written off quickly. But it couldn’t last: Hakeem Olajuwon, from Nigeria, became a league icon (while observing Ramadan every season). Eventually, Dirk Nowitzki, from Germany, and Manu Ginobili, from Argentina, followed. They redefined the range of possibilities for foreign players.

Now, three of the league’s most brilliant young stars — Kristaps Porzingis, Joel Embiid, and Giannis Antetokounmpo — are re-defining that range once again. They are giants with the agility of much smaller men; they are singularly talented in ways we’ve never quite seen before. Collectively, they’ve been referred to as “unicorns.” And they’re all from outside the U.S.

Of the three, Porzingis has traveled the most traditional foreign-player route. A Latvian national, he got a few years of burn in the Spanish leagues before being drafted by the New York Knicks in 2015. This season, as the Knicks have sputtered and splintered, Three 6 Latvia remains a bright gem of hope: 7’3”, silky, and unafraid, he is the future of the franchise.

Embiid’s path has been more roundabout. Coming up in Cameroon, he dreamt of a career as a pro volleyball player in Europe. Then he was spotted at a hoops camp by his countrymate (and ex-L.A. Clipper) Luc Richard Mbah a Moute and was re-routed to Kansas, where he dominated college ball. Foot injuries threatened to chop him down before he ever took the court for the Philadelphia 76ers, but this season he’s bloomed.

Antetokounmpo’s story is the most dramatic. He was born in Greece to undocumented Nigerian parents, and helped out the family by selling trinkets and serenading tourists with Christmas songs on the streets of Athens. “Because my parents were illegal, they couldn’t trust anybody,” he told Sports Illustrated earlier this month. “They were always nervous. A neighbor could be like, ‘These people are making too much noise, their children are making too much noise,’ and the cops could knock at our door and ask for our papers and that’s it. It’s that simple.”

The American tourists that buy sunglasses from African men in European capitals don’t, as a rule, stop to consider those vendors’ life stories. Antetokounmpo forces that to change — he cannot be ignored. Last offseason, he signed a $100 million deal with the Milwaukee Bucks. This February, he’ll almost certainly be an All-Star for the first time. Lovingly, the fans call him the Greek Freak.

It’s “Greek” that is the operative word there. Antetokounmpo was born in Greece, and grew up in part in its traditions. (According to the SI piece, his regular Wingstop diet is buttressed with gyros and lamb chops from Milwaukee’s 24-hour Omega Restaurant). In the past, Nikolaos Michaloliakos of Greece’s ultra-right wing party Golden Dawn has viciously attacked Giannis: “If you give a chimpanzee in the zoo a banana and a flag,” he’s asked, “is he Greek”? Michaloliakos can keep ranting. Giannis is Greece.

He’s also increasingly, rapidly becoming American, as are his international peers. Like Dirk before them, Giannis and Kristaps’ accents are vanishing fast. But they carry their stories and their heritages with them. Recently, Porzingis was named Latvia’s Athlete of the Year. He couldn’t make the ceremony: the Knicks were playing Orlando. At the event in his stead, some of his female relatives sang a song in his honor, and in the process exposed us to the greatness of traditional droning Latvian choral music. I mean, listen to this thing: it absolutely bangs.

The NBA is not only our most diverse pro sports league, but also our most progressive. Its players wear “I Can’t Breathe” shirts on the court. Its commissioner, Adam Silver, politely encourages political expressions. Privately, players' agents may well be aghast at the damage this can do to their clients' earning potential: White Nationalists buy sneakers too. In public, though, it’s explicit, and much discussed: unlike their ’90s predecessors, who were in part defined by their neutrality, our generation’s hoops stars are not interested in playing Switzerland.

As we roll forward to a dreaded inauguration day, and the four years to come after, NBA players will have to decide how engaged they want to be. The normalization of Trump is going to accelerate inexorably; many may very well feel forced to retreat. But there have been encouraging signs: already, a handful of teams have made waves by boycotting Trump hotels.

Meanwhile, independently of the course of its politicization, the multiculturalization of the NBA will only get grander. The pool for next year’s draft is highlighted by prospects like Bam Adebayo, born in Newark, NJ to Nigerian parents, now playing at Kentucky; Lauri Markkanen, a Finn playing in Arizona; and Frank Ntilikina, a Belgium-born Rwandan kid now playing in France who credits his facility with English to loving American hip-hop.

Also: slated to return to the Sixers next year from injury is Ben Simmons, an Australian phenom (with a dad from the Bronx). That means he’ll be joining Joel Embiid, who’s spent a lot of time making sure Ben feels included while out rehabbing.

If he wins, he's gonna deport you..... https://t.co/yswmQrNLzn

— Joel Embiid (@JoelEmbiid) October 20, 2016

The leader of the free world is actively opposed to the benefits of cultural immersion. In 2002, when Trump was visiting his wife’s family in Slovenia for the first (and only) time, he landed at 8pm and returned to the airport by midnight. (Also, again: fucking taco bowl.) But Trump and the U.S. are not alone in their embrace of isolationism and insularity. Along with the U.K., similar political movements — hostile to immigration, promising a “return” to an undefined past era of glory — have taken power or are threatening to do so in the Netherlands, France, Poland, and Hungary.

To both its players and its fans, the NBA offers an alternate global vision. It’s one where multiculturalism is still celebrated as a virtue, not fought as a blight. These kids rep their ancestry and their place of birth as seamlessly and effortlessly and proudly as they do their new American homes. By the sheer fact of their existence, and their excellence, they reject an imaginary white monoculture. And the best thing about it? All Giannis, Kristaps, and Joel — and all the great ones coming up next — have to do to support that vision is flourish. All they have to do is ball.