Courtesy of Leasho Johnson

Courtesy of Leasho Johnson

Although he’s currently serving a life sentence, Vybz Kartel released an album, King Of The Dancehall, and definitive summer anthem, “Fever,” in 2016. But the charismatic dancehall emcee, and his music, are often the subject of great public debate in Jamaica and abroad due to his frank, and often lewd, musical references to women, sex, and the politics of the Jamaican ghetto. Kartel, like many other Jamaican recording artists, are a crucial part of that country’s social fabric because they are fiercely championed and challenged public figures.

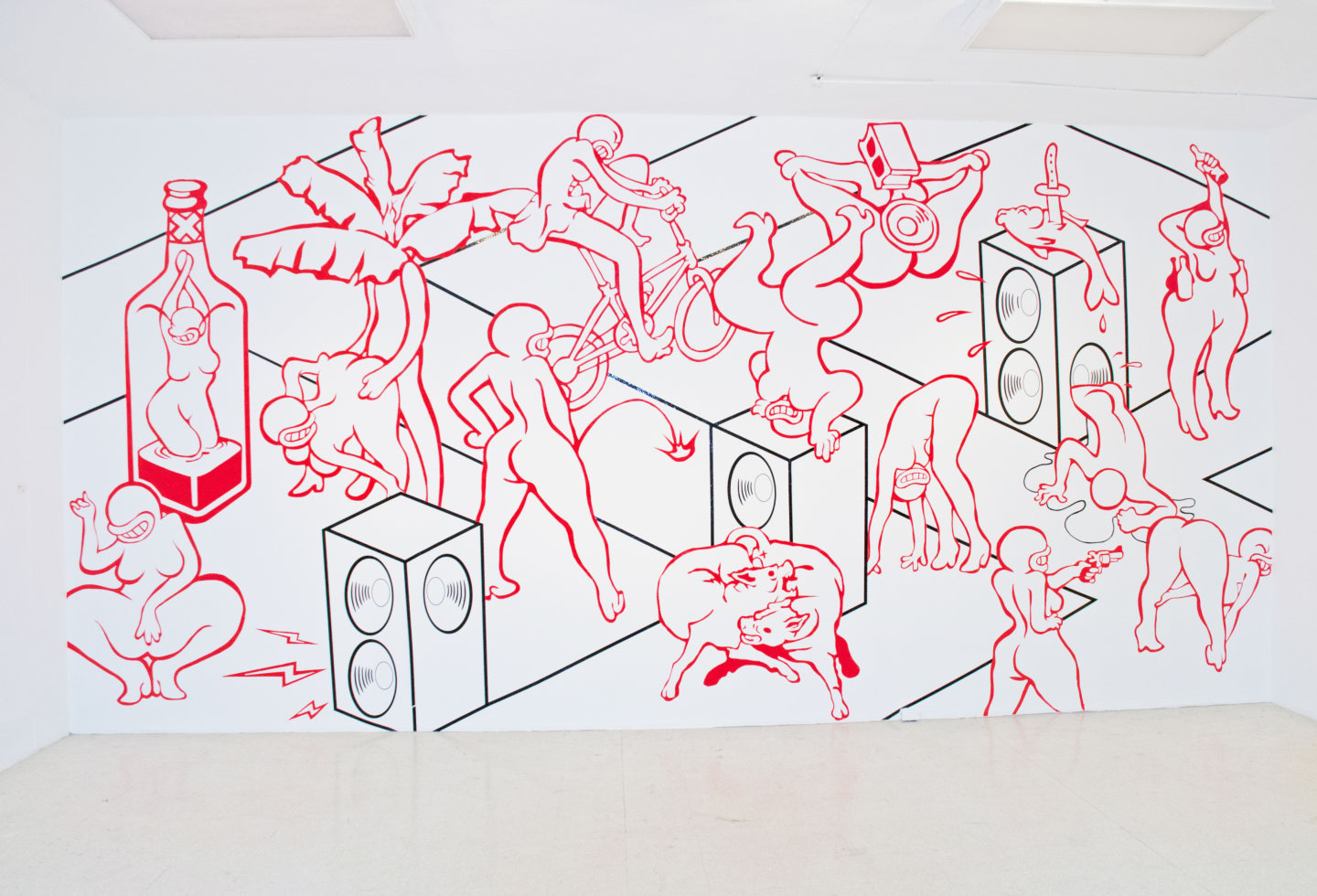

Leasho Johnson (pronounced LAY-sho) is a graduate of Jamaica's prestigious art school, Edna Manley College, who grew up in his artist father’s studios. The younger Johnson creates mixed media visuals, sculpture, and textiles that respond to and reflect the realities of Jamaican music and society: Vybz Kartel’s lyricism provides equal parts ruckus and roots for Johnson’s cartoonish figures. Dancehall’s relevance to youth culture and its influence on the island nation’s norms and mores is comically-illustrated through Johnson’s deliciously plump and gaudy fictive characters, including ‘Pum-Pum’ whose round ass is proudly on display while braced against a sugar cane trunk, and ‘Monkey Man’ who is seductively wrapped around a ripe green banana. This intentionally blurs the lines between high and low culture in modern Jamaica, a common struggle between the island's working class communities and privately educated middle-class.

And Johnson’s hybrid of realism and pop art is distinctive amidst a small and traditional local art scene. “Jamaicans like humor, controversy, and sex but you wouldn’t see that explored in fine art,” he said when we spoke. Johnson recently completed a residency in Liverpool, U.K., and was also part of the U.K.’s largest exhibition of Jamaican art. In the coming year he’ll participate in shows at the National Gallery of the Bahamas and Philharmonie de Paris. He spoke with The FADER about finding artistic inspiration in everyday Jamaican culture and symbols.

Courtesy of Leasho Johnson

Courtesy of Leasho Johnson

Courtesy of Leasho Johnson

Courtesy of Leasho Johnson

How did visual art become your medium of choice to tell this story of the island?

My father was an artist and I grew up with him using his hands for sign-making, sculpting, and in many other mediums. He had several studios and I would always be around — he often tells stories of how, as a child, I would attempt to help with his art and kind of mess it up! My dad graduated in 1984 from Jamaica School of Art and Crafts, the first artistic institution opened after independence from England. I was born in that same year, and so I consider myself to be an extension of his artistry. [Being an artist] was a bold move to make in a Caribbean country at that time, so I acknowledge his bravery to pursue something different.

When did you realize dancehall could be an entry point for telling visual stories?

When I started producing my own work I was considering the people. The narrative of Jamaica was controlled by upper classes who wanted to be more like the European benefactors. I had an opportunity to showcase my work in a gallery here and I wanted it to be a ‘fingers up’ to say, this is truly us! This is the foam at the top that comes from years of repression. Dancehall is highly performative. It’s singing and dancing, but I wanted to create a new understanding of the genre to see what it would look like as a painting, as a graphic design, or a sculpture.

[When I was] in high school, you would always hear dancehall being blasted outside or in the hallways. I was the kid who wanted to hear techno or rock — something that wasn’t so nasty. I knew all of the songs very well but I couldn’t relate at the time. When I got to college I met other young people like me who didn’t really enjoy dancehall — except they hated it and were actively trying to distance themselves from it. I thought it was ridiculous to culturally separate yourself from something so ingrained in us and our country. That’s when I decided to completely embrace dancehall, including the humor and expletives that are part of our everyday language.

Courtesy of Leasho Johnson

Courtesy of Leasho Johnson

“Dancehall is an interesting space where women can embrace aggressive sexual energy and still be read as attractive and feminine. That kind of confidence is purely Jamaican.”

It’s interesting that you didn’t like dancehall at first. What do you find compelling about it now?

Vybz Kartel was the artist who built the bridge back to dancehall for me. He smartly comments on gender roles in Jamaica, Caribbean masculinity, and American-influenced materialism. What Vybz did with Jamaican patois is similar to what happened in Pop Art where brands became the art and you’d see household names as images in the gallery: he showed that dancehall reflected us as global citizens.

Shabba Ranks and Buju Banton are two of the most impactful musicians. Buju's “Boom Bye Bye” [a song with homophobic lyrics] is something we can’t get rid of, but it also needed to happen. Dancehall [shows] that we don’t take ourselves too seriously. I’m still getting used to going to a clash and hearing abrasive homophobic lyrics but, on other hand, I will go to a gay party where the same songs are being played and the crowd is almost role-playing and singing along. It’s a dynamic psychological space; sometimes you choose to feel the music. There’s some humor to find in the dedication to straightness.

When I first started to create the characters in my work I was inspired by Spice. At the 2011 Reggae Sunsplash, Spice came out on stage with her legs spread eagle and a man on either side carrying her and I thought, OMG. Dancehall is an interesting space where women can embrace aggressive sexual energy and still be read as attractive and feminine. Of course this stems from Lady Saw; that kind of confidence is purely Jamaican.

You’ve talked about the way Jamaican society can be stratified, and said that your work considers ‘the people.’ Who do you make art for?

My work contains truths and ideas we need to confront as a people, but I’m also being investigative: I want to see how people will react. My last public mural ‘Back-fi-a-Bend’ [a tribute to women laborers, titled after a Kartel song] was removed less than three days after installation because of pushback from an older generation. They want to [obscure] conversations about sex and gender from a younger population, who are already listening to Popcaan on the way to school in the morning!

I’m creating a parallel for Jamaicans to understand art and themselves by using everyday objects that are primary to us, and representational of our history and way of thinking. I want people to be curious about Jamaica and ask questions outside of ‘rice and peas and Bob Marley.’ We are a highly-spirited and highly-resourceful people who can take simple things and turn it into gold; I see the the beauty in those simple things and want to put that on a pedestal.

Courtesy of Leasho Johnson

Courtesy of Leasho Johnson