A wall is just a wall

Toni Hafkenscheid

A wall is just a wall

Toni Hafkenscheid

Spatial awareness is urgent for black people, particularly in an era of state-sanctioned, and now Trump-mandated, human rights rollbacks. Some artists have recently made work highlighting the different ways blackness and space are related. In an essay for The FADER, Rawiya Kameir described Solange’s affinity for her camera zoom as an aesthetic way of reframing black womanhood and humanity. Similarly, Hamilton, Ontario-born conceptual artist Kapwani Kiwanga’s newest exhibition, A wall is just a wall, currently showing at The Power Plant in Toronto, is all about how we are disciplined by our physical environments.

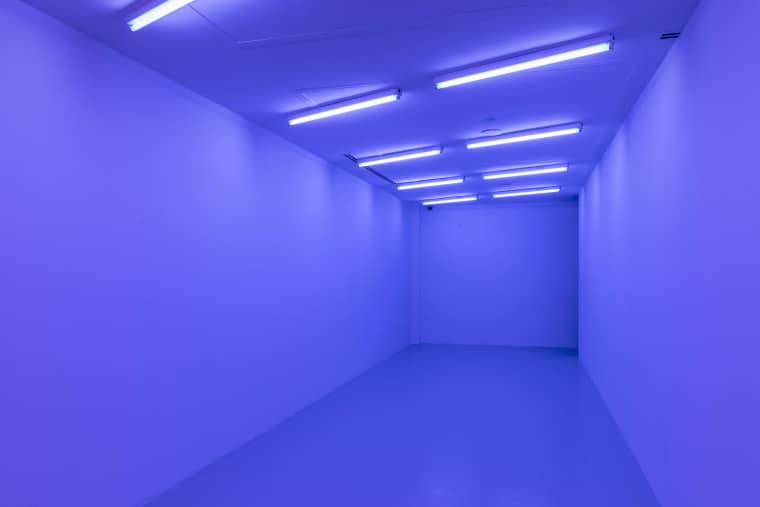

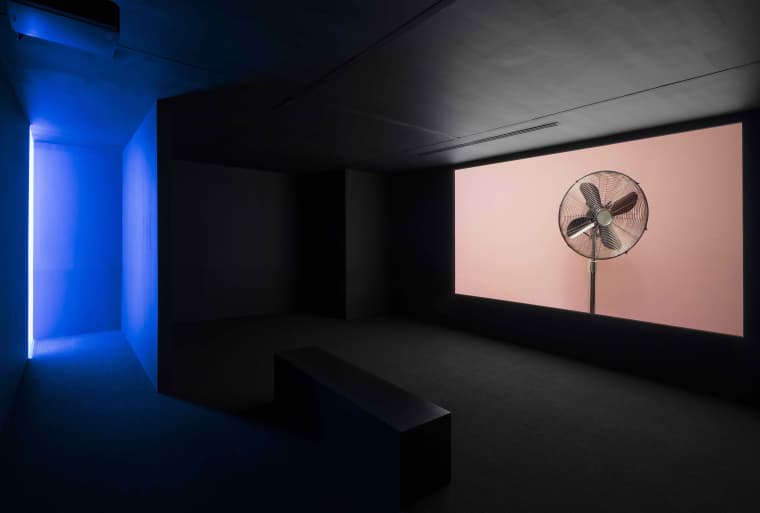

A wall is just a wall creatively reproduces the surveillance and control embedded in certain architectures. Kiwanga paints a bare corridor in shades of pink and floods it with fluorescent lights, while around the corner a silent film deconstructs a triptych of walls. Between the two spaces, a barely audible disembodied voice recounts historical facts and anecdotal observations gathered during the artist's research. This looped narration contextualizes Kiwanga’s spatial experimentation: it describes various government efforts to manage people in public space, interior design tactics for influencing emotion, and strategically manipulated colonial architecture. The simple exhibition shows how space can be manipulated to control not only our moods, but also our freedom of movement.

The FADER spoke with Kiwanga, who now lives and works in Paris, about the history of color and architecture on prisons, and how we can push back against spatial surveillance.

A wall is just a wall

Toni Hafkenscheid

A wall is just a wall

Toni Hafkenscheid

Toni Hafkenscheid

Toni Hafkenscheid

How did you start thinking about architecture and its effect on behavior?

I’m generally really interested in power structures, particularly disciplinary architecture. Just walking around the streets I see how more and more public spaces are being constructed to exclude people — particularly people who don’t have private spaces, whose only space is public space. Also, an image of two-toned walls had stuck with me. They call them Dado Paint, and it’s usually a darker color on the bottom and another color on top. I had seen this over and over again in the global south and was curious what it was and where it came from. People say it’s for the practicality of cleaning the walls easily, or to repaint them without having to paint the whole wall. But because they were always in public institutions like schools and hospitals, I was wondering if there was something else behind it. It became symbolic of questions of hierarchy and splitting people behind the line, below the line, staying on line, staying in line.

Where did your research lead you?

A couple of elements came up. One was this paint color called Baker-Miller Pink which was applied to walls in a correctional facility in Seattle in 1978. They painted their walls this pink with the hope of calming down violent prisoners, based on research done by Alexander Schauss who had done a lot of work around psychology and color. He found that this particular shade of pink was meant to have a tranquilizing effect, it would lower the heart rate and respiration. This pink became really popular and ended up being used in locker rooms and all these different places, especially prisons. It's still used in prisons today.

Was Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon [an architectural surveillance design for prisons] an influence on this project as well?

The idea of the Panopticon is there, but I was trying to avoid referencing the text so much. There was a question, of course, of the power of being seen or of not being seen. That’s referenced a bit in the exhibition through lights and also in the video. The questions of surveillance and seeing is of course at the core of this idea of controlling of bodies.

Yeah, as a black person I often feel vulnerable in certain public spaces. I got that same feeling in your installation: there are all these bright neon lights in that open corridor and nowhere to go. It made me feel exposed somehow.

At one point I was thinking of using actual sculptural elements that would be either two-way mirrors or glass, but I ended up focusing on the color. I guess there is a heritage of black bodies — bodies of all people of color — that have been marked and tracked, that have always been visible either through how they’re covered or uncovered. When you go into prisons, you’re stripped to be searched — not always, of course — and that brings back the whole question that you are, again, completely nude. So who has the power to look? But then again, there’s always the power of looking back, which we don’t often talk about.

“Things are constructed but that doesn’t mean we can’t modify and fight against them.”

A wall is just a wall

Toni Hafkenscheid

A wall is just a wall

Toni Hafkenscheid

Toni Hafkenscheid

Toni Hafkenscheid

Can looking back through the glass, or at the surveyor, be a way to neutralize invasive surveillance?

My first thought is, ‘Well, let’s look at and make evident the things that maybe we don’t always see so evidently’ through subtle differences in technologies, colors, lights, or whatever else is used to exclude or control different bodies. Although in this work I’m referencing systems that try to control bodies, I think there’s always resistance there. That’s why the title is A wall is just a wall, which is a reference to Assata Shakur’s poem, i believe in living, where she writes, "a wall is just a wall/and nothing more at all/It can be broken down.” She’s talking about prisons, as well as everything else. Things are constructed but that doesn’t mean we can’t modify and fight against them.

The stakes of government surveillance are higher than ever given the recent, swift targeting of the most marginalized and vulnerable by the Republican administration in the United States.

Power in our current political moment is much more visible than it has been. I mean, it’s now being unabashedly shown, which is an interesting thing. But I don’t know if that means that power is so self-assured that it doesn’t need to have the Wizard of Oz curtain in front of it anymore.

We change our strategies and our techniques [of resistance] depending on the context we’re in. We’re in a time where power has changed but the fundamental tussle that’s always been there, between domination and those who are dominated, is still ‘The Question.’ Some moments may be less tense than others. Power changes its dance, flavor, cadence — but it is always there.