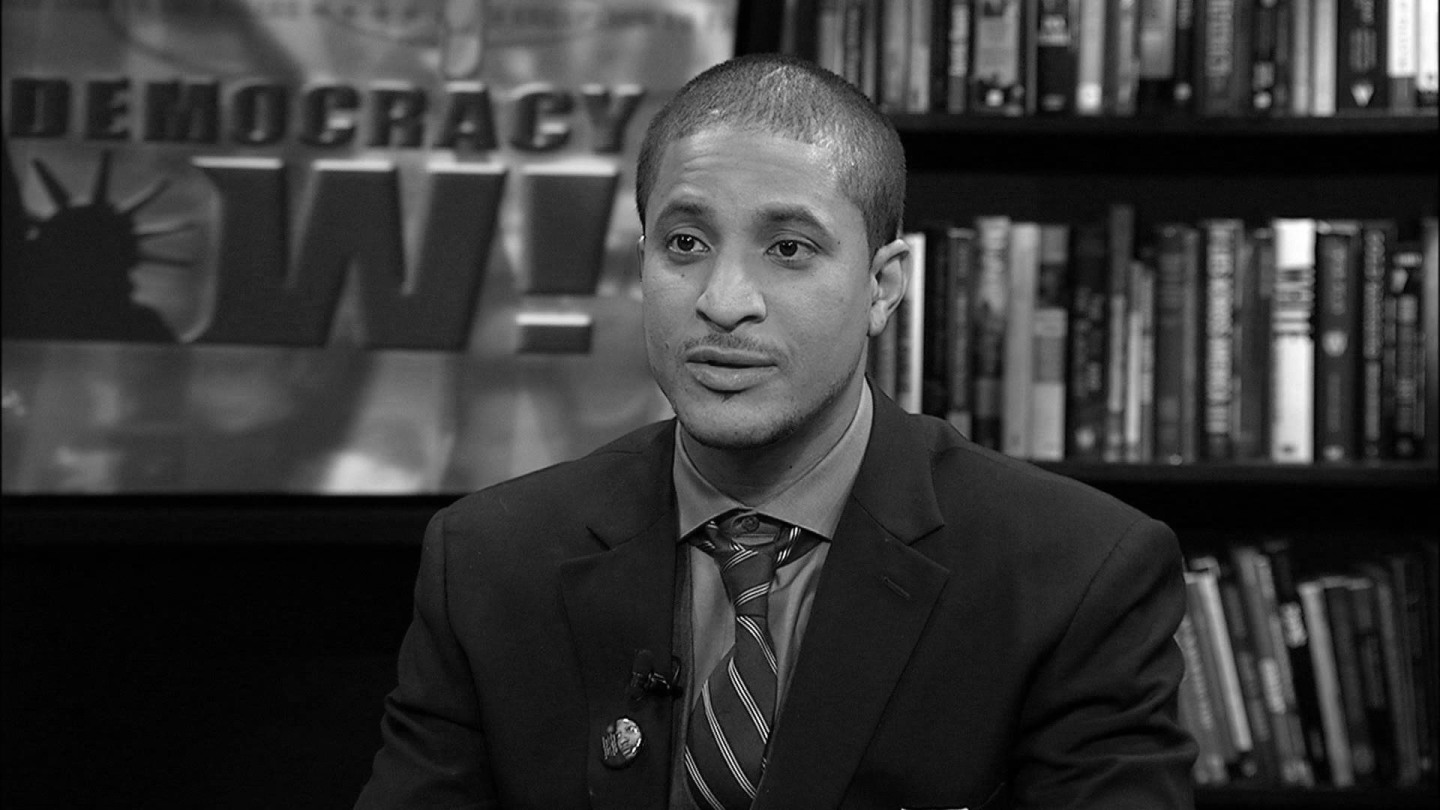

Akeem Browder.

Screenshot via Democracy Now!

Akeem Browder.

Screenshot via Democracy Now!

The great irony, and the even greater barbarity, of the American justice system is that justice is so seldom served if you are black or Latino. For three years on Rikers Island, Kalief Browder rotted in a man-made hell: he was frequently assaulted and denied food by guards, harassed by inmates, and spent much of his time in solitary confinement. Browder, who was charged for the suspicion of theft but maintained his innocence throughout, was never convicted and eventually released. In June of 2015 at the age of 22, mentally and emotionally scarred from his days on Rikers — while inside, he attempted suicide multiple times — he took his life.

The horrific result of Browder’s death spurred a national outcry, and a renewed demand to shut down Rikers, New York City’s largest and most notorious jail complex (it is estimated to house 10,000 inmates). “Kalief was a kid, like any other kid that grows up in a black household,” Akeem Browder told me in early April. “He was the last one in the line. I guess what I’m really trying to express, basically, is that he had a lot of examples before him to fall back on when it comes to experience. He was more protected.” Still, the shelter of family is not often enough to save youth of color from falling prey to America’s ravenous criminal justice system. (Kalief’s story is the subject of a recently aired six-part docu-series on Spike.)

I spoke with the elder Browder just days after Mayor Bill de Blasio called for the closure of Rikers, which he said could take up to 10 years and described as a “very serious, sober, forever decision.” It was a small victory, but Akeem, who is 34 and the founder of the Campaign To Shut Down Rikers Island, says bigger battles remain (fortunately, the Raise the Age bill was just signed into law). Below, in his own words, Akeem Browder details the fight to close Rikers and how we can better safeguard young black and Latinx men and women from being swallowed by the carceral state.

AKEEM BROWDER: As the founder of the campaign to shut down Rikers, what we called for was the immediate shutdown of Rikers — that’s what we marched for in the streets. That’s what we marched and brought to Rikers Island, that’s what we also advocated for in Albany, going upstate and petitioning to raise awareness. Also, there’s Kalief’s Law, which I had a hand in writing with State Senator [Daniel] Squadron, which would further release more people from Rikers because they’ll get a speedy trial. We called for this. We advocated for this; we put in our time and invested our interest into this. And yet, when [New York Mayor Bill] de Blasio decides to make his press statement, it comes at an advantageous time for him, during re-election season. The people of New York deserve the victory of actually getting that hell hole shut down. But I won’t let Kalief’s name be used as a tool to advocate for new prisons, [which is what was proposed]: to open up new borough-based jails. We’re still advocating the immediate shut down of Rikers, not a 10-year plan.

I don’t advocate for prison reform. I think we can do better, and New Yorkers actually have the same opinion that we can do better. We can reallocate the funds that it costs to keep Rikers operationally funded — we can do better with that money, with new programs for psychotherapy, or mentorship, or use that money to create programs within the community that stop individuals from going to jail in the first place. That money can be used to create jobs instead of disenfranchising people to become part of a population that is not considered citizens. There is a lot more we can do with this money instead of just doing the same thing, which is continuing the practice of the penal system.

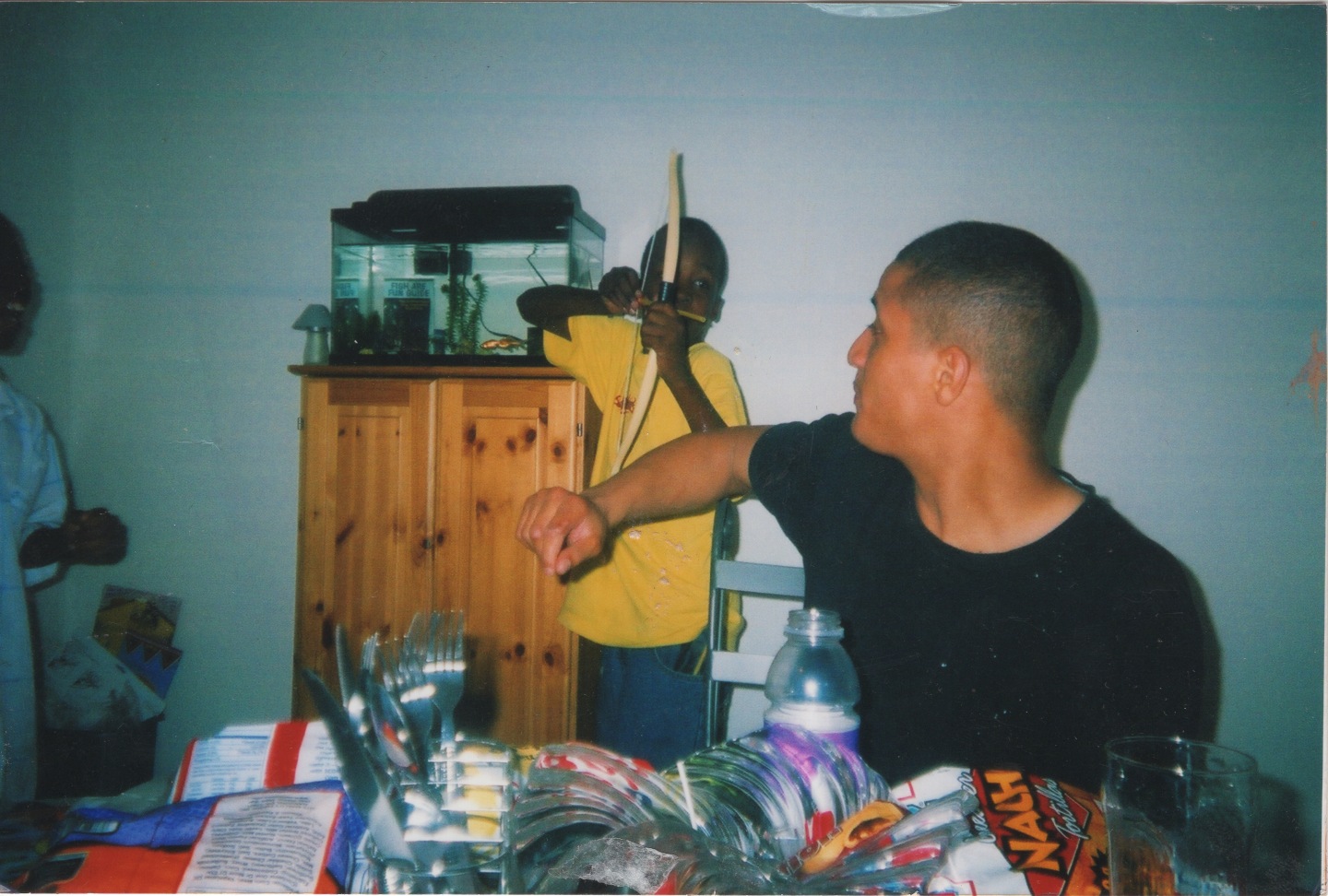

Kalief and Akeem at the Browder home.

Photo courtesy the Browder Family/Spike

Kalief and Akeem at the Browder home.

Photo courtesy the Browder Family/Spike

“I don’t advocate for prison reform. I think we can do better, and New Yorkers actually have the same opinion that we can do better.” —Akeem Browder

I was actually registered at 14, going on 15. I was sent to Rikers. I later worked for the Department of Corrections when Kalief was there. In both I realized: you can’t know what actually happens on Rikers unless you actually were a detainee there or working there. You’re gonna get two different realms of what happens because you have the side of when you’re there, and you’re witnessing the injustice, and then you have the side where you’re witnessing it from a different perspective as a free man going home every day. While Kalief was locked up, I ended up quitting six months after he arrived. That was strictly off morals. I don’t believe anybody should be working [at Rikers] seeing or witnessing the abuse that happens, and then continue just because they’re making a salary.

Instead of incarcerating and doing the same penal system that really just tortures our citizens, or our people, what we should be thinking about is real corrective behavior, or real corrective treatment that prevents. We could focus our efforts on preventative workshops instead of waiting for people to go to jail, and then punish them and so-call “correct” them.

We need more organizations that are dedicating their work to helping transition people from jail or prisons to society. Exodus Transitional Community has been supportive of my family and getting Kalief’s story out there since day one. They’re a reentry-to-society program that services 1,500 people a year. We need more services like them that are nonprofit organizations. You have people who are returning, in the thousands, from these long-absorbing sentences of 20 to 30 years; and now they’re coming home and they don’t have the funding or the services necessary to see that their return to society is successful.

Fortune Society — they’re huge, they’re nationwide — also does this kind of work, and is similar to Exodus. But there are not that many programs out there like that, so we gotta be more supportive and get the city to understand that without services like this that prevent people from going in, we’re always going to have this perpetuated system of abuse. This culture of abuse doesn’t just exist on Rikers, but in other prisons throughout the state like Fishkill [Correctional Facility], which is actually a really notorious prison. And with Rikers, we’re talking about jail. There’s a difference between a jail and a prison. These people are taken there in their plea bargains while on Rikers, then go upstate to serve their time, and then they’re getting killed up there — committing suicide, getting beat to death, being raped.

Out of all this stuff, you know, a lot of people tell me, “Akeem, the terms that you use are so harsh,” because I think [that what the] police departments across New York City do is kidnapping. What they did with Kalief was strictly kidnapping, and some people just think that these are harsh terms that I use. And yet, are we not talking about harsh times or harsh situations? A person goes to jail for allegedly stealing a backpack? If we’re not talking about harsh terms, I wouldn’t use harsh terms to speak about it. I won’t be quieted just because it hurts or offends your ears to talk about stuff that really happens in black and brown communities.