Standing On The Corner.

Photo by Devlin Claro Resetar.

Standing On The Corner.

Photo by Devlin Claro Resetar.

Since its conception in 2014, Standing On The Corner has had many lives. The brainchild of 21-year-old New York-Puerto Rican artist Gio Escobar, it first found form as a guitar-based live group called Children of the Corner, in name an homage to Harlem rap collective Children of the Corn. Those early efforts grew into Standing On The Corner, for which Escobar wrote several tape machine-recorded songs that he initially never intended to be played out. “It’s just something that came out of me,” he shared. However, with the encouragement and assistance of 21-year-old New York-based producer Jasper Marsalis (also known as Slauson Malone), the two friends worked to bring those songs to their fullest potential in the form of Standing On The Corner’s 2016 self-titled debut — a drum-machine-assisted blend of jazz-inspired woozy vocals, soul-drenched strums, and heart-guiding keys that makes me feel like I’m slowly floating and swirling between the brownstones of my Bed-Stuy block.

On Monday, September 11, Standing On The Corner dropped their newest mixtape, Red Burns. A departure from their more traditionally musical and album-formatted debut, Red Burns is an hour-long mixtape that’s sounds and feels more like a meticulously compiled sonic-scrapbook documenting a tumultuous moment in time. In sound and in sentiment, it embodies the stuck, frustrated feeling that young black and brown people in the world often face, particularly in today’s political climate — one of “impending doom,” says Escobar, and an “obsession with the end of the world as we know it.” Though led by Escobar with production from Marsalis, Red Burns is a product of collaboration with SOTC’s immediate friends and creative community, both in instrumentation and in inspiration. “There are friends who don’t necessarily play anything on the album,” Escobar shares, “but their influence, it comes through and it’s infinitely important.”

Sonically, Red Burns is comprised of many things: a handful of free jazz and rap-influenced original songs and compositions (some slow and steady and featuring SOTC’s signature warped vocals), which are sometimes interrupted by either cacophonous or complementary samples and drum machine mishmashes. There are also several seemingly archival samples — a poem about city blocks, snippets of radio you might pick up while walking past open Brooklyn windows — and a few impeccably voiced skits, that further paint a picture of Escobar’s life in New York City.

Visually, the project’s website serves to contextualize the mixtape with a collection of thoughtfully selected GIFs and memes.“There’s the one GIF on the page of that kid throwing a tantrum,” says Escobar. “If we had to choose a thesis for the [mixtape], it was that kid.” Taken as a whole, Red Burns is a journey, and it’s meant to feel like one. As Escobar explains, for him personally, making it was “a process of responding to the world in a way. Everybody’s just trying to figure out how to react. Sometimes it comes out in this weird ass album.”

During a visit to The FADER offices last week, Escobar and Marsalis talked about Red Burns and the story behind it, why they decided to contextualize their music with memes, and the importance of their creative community in New York today.

Your new mixtape, Red Burns, came out last Monday. What’s the significance of the title?

GIOVANNI ESCOBAR: Red Burns is a title that I'd been sitting with for a while. I didn't know quite what it meant, I just liked the way it sounded. I finally came to know what it was [during] my most recent trip back to Puerto Rico, in April or May. I had been speaking a lot more to my family about why we are where we are. How everybody ended up in their specific predicaments. It's just crazy how far back people go — how far you've gone from the earliest ancestors. Discovering all of these bad things that happened to us over time and trying to find a reason for them. I think, ultimately, that's what Red Burns is — it’s a curse, that I think people of the diaspora have. I guess the root is, ultimately, manifest destiny — this willingness of colonial white settlers from Europe who chose to violently alter the history of another people for the rest of time. We can never undo these things.

There is constant conversation about decolonization of language, but this thing is going to be with us for the rest of our lives. This is actually [a] man-made tragedy, and this is going to happen until the end of time. I don't see [the curse of] Red Burns ever going away, you just have to live with it and it will be there on your most exciting days, your worst days. It's sad as shit. Realizing this and coming up with it, doing it in a way that is artistic and important, it's just by chance. I didn't create this, it's always been there for people to find.

This project feels so multimedia — the homepage features a collection of memes and GIFs. Then you have the album art and tracklist, additional components of excerpts and quotes. The mixtape itself sounds like an audio-scrapbook — you’ve got skits, outside recordings. What’s the thinking behind these multiple forms?

ESCOBAR: I think that has less so to do with decisions we make in what SOTC is, but moreso how we feel the music can best be served by all these other things. I think contextualizing what we do is just as important as the way we actually made or composed the songs because, I think we’re very aware how inaccessible some of the things we do can be. There are other ways to tell the story that don’t only have to do with music. I think being confined to being a musician is frustrating sometimes. Not everything you feel can come out in a song, and that has to do with restrictions of your own musical teaching or words themselves. We talk about being frustrated about stuff like that a lot.

With Red Burns, we had more to say about how we feel, more than trying to be good songwriters. We were going through a lot while this album was coming to be. There were personal things and... impending doom. I hope that gets across in the album, this obsession or theme with the end of the world as we know it. You think about something like Trump — and I hope to not make this too much about politics — but that really crushed us. Not that we were surprised, but, that happened and we were there for it. How do you conduct the art that you’re trying to conduct while something like that is happening? At least for me, it’s like, How do I write a love song ever again? It just didn’t feel important anymore. Somehow, things like a skit or a poem just felt more appropriate on what we were trying to say through this album.

JASPER MARSALIS: To add on to that, How do you capture an emotion, but not lie to someone? I feel like that’s a huge issue in songwriting. At a certain point, you have to create this emotion that has to be consumed by people who are listening. Also, a lot of our influence does come from outside of music. I feel like the website is an homage to all the things that are not “art” so to say.

Screenshot of StandingOnTheCorner.com homepage

Screenshot of StandingOnTheCorner.com homepage

You mentioned contextualizing some of your music.

ESCOBAR: We communicate a lot in the things we see on the internet. Memes are really important to what we do because, I think they’re ingrained in our culture — at least mine and Jasper’s day-to-day, I can’t say that for everybody. There’re certain things that happen on the internet, that just capture how we feel. Like there’s the one GIF on the page of that kid throwing a tantrum. If we had to choose a thesis for the album, it was that kid. Sometimes, it’s just easier to show your inspiration than deduce something from it and put it in a song.

MARSALIS: Also the dab, too. That’s a big deal. Like, how do you translate a dab into a sound? How? I feel like we did a pretty good job. [Laughing]

ESCOBAR: It was never something we tried to force, the sonic dab. There were these dabs in the songs, and we worked really hard to make them work, but I think we perfected it.

MARSALIS: To speak about what Gio was saying about the politics thing, in some ways, this is more of a natural way to address issues. These things are already have meaning, we don’t need to make more shit, all that needs to be done is contextualizing, and that’s what this mixtape has done for me.

ESCOBAR: For me too, it’s a process of responding to the world in a way — like what it means to go out and protest, like have your body physically there. We did that, and it’s not the most redeeming thing, you know? I don’t know what it is about it, and that’s not saying I don’t agree with it, but I think everybody’s just trying to figure out how to react. Sometimes it comes out in this weird ass album.

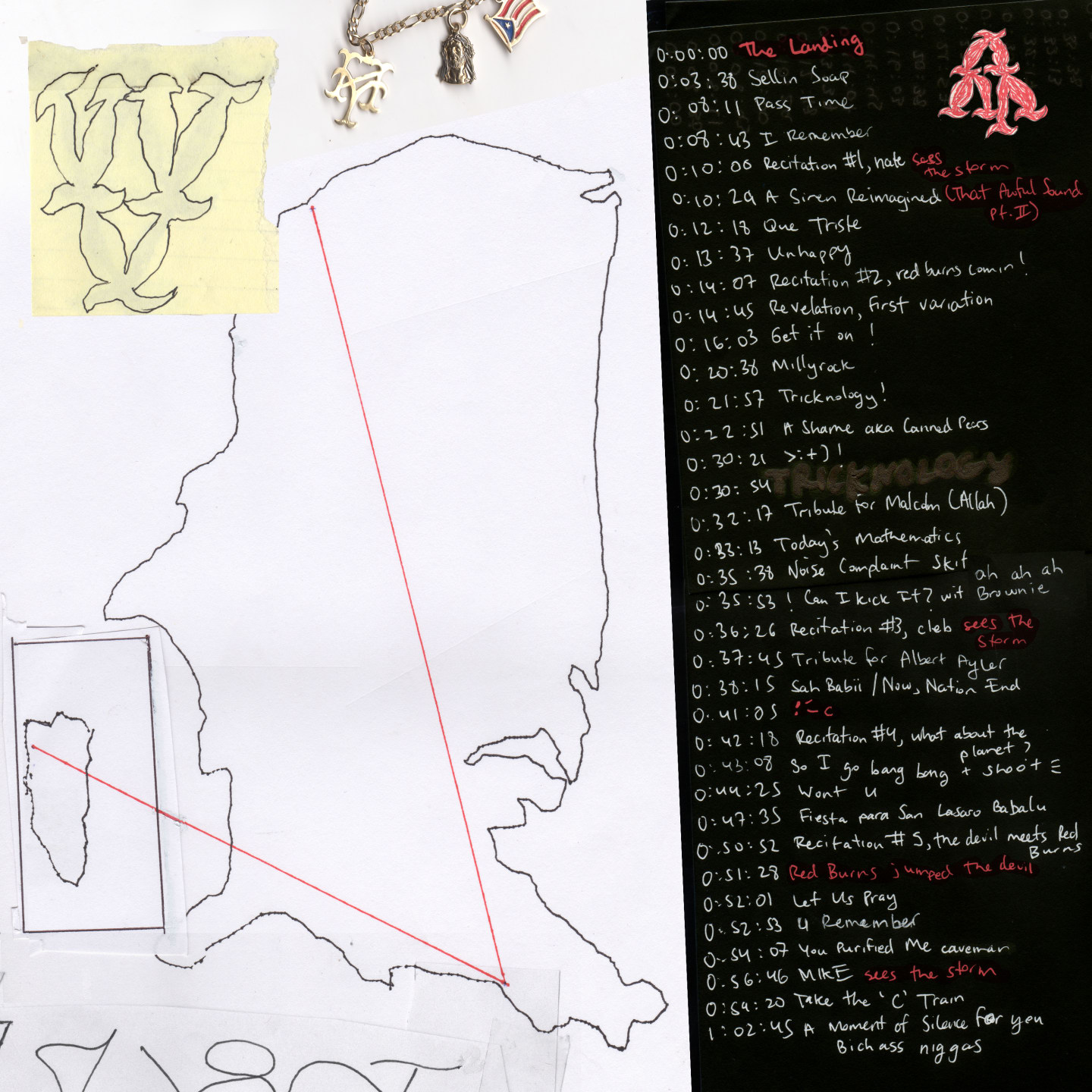

Red Burns by Standing On The Corner.

Art by Jasper Marsalis.

Red Burns by Standing On The Corner.

Art by Jasper Marsalis.

You guys dropped both projects on 9/11. Was that intentional? What is the significance of that for you? The first project’s cover art also alludes to the towers.

MARSALIS: The first time it happened by chance. We didn't realize we released it on 9/11 until like, an hour later. The cover art —

ESCOBAR: — that wasn't on purpose. The release date on this one was sort of the same. We have that motif on the cover again — when it's downloadable, there's an alternate cover that's a photo of us in front of airbrushed towers. Whether or not it came out on that actual date, we still chose this imagery for a reason. For me, it has to do with my relationship with New York, maybe less so with the actual day.

Growing up in New York, it's very egotistical in a sense, you really do believe everything is happening here. You're sort of obsessed with your city because people are proud to be from here. I grew up around a lot of hip-hop and house music, and a lot of that is so New York centric. You think, New York is really the place to be. But I think, 9/11 was the first point at which I felt New York as a vulnerable place, and not as this center or all-important place. It felt penetrable for the first time — if something bad were to happen, why wouldn't it happen here? Look at all of this stuff that goes on, not all of it is so great. I don't think I thought of that as a kid, I was shaken. I still have this anxiety about being here, everyday. I used to have this reoccurring dream that I would be in this crowd of people and it would be swallowing me. I think that's a New York thing. As much as you love this place, it's very unforgiving and harsh. It's not easy. There are worse places to be, granted. I think [using the imagery of] the towers, that's the perfect way of saying that without saying that. I don't think everybody felt so fondly about those towers, nobody wanted to see them go, but I think it meant a lot of things for a lot of different people. It's become this symbol of America, or American victimization, because of terrorism, but to everyone else who is here, those weren't positive places. They were really dead pan steel — there's no mythology to it, it's just business. I mean, that's always how I felt about it, I guess.

Gio Escobar.

Photo by Devlin Claro Resetar.

Gio Escobar.

Photo by Devlin Claro Resetar.

Gio Escobar.

Photo by Devlin Claro Resetar.

Gio Escobar.

Photo by Devlin Claro Resetar.

There’s a super special energy brewing within the creative scene that you and your friends have been cultivating, especially over the past year, that’s starting to pick up and resonate with more and more people. Why do you think it’s special or important, specifically right now in New York?

ESCOBAR: It just felt so long that brown and black people in this New York art scene be prioritized. Maybe there are things that have to do with that, like putting out proper output or doing things the right way. To me it feels cosmic that we are communicating these things at the same time without much intention beforehand. I think a year ago, none of us saw this scene looking the way it does. I think we're grateful, and it's pent up frustration with the rest of the world, but even with our own communities, places like we felt we should have been allowed. Us not being accepted in that way, it had an effect that maybe at first made us all very sensitive. Being excluded is no fun, but at the end it's ultimately led to this blessing of this community of us who, these are our values. Black and brown people, this is what is important to us. It's a crew and not so accepting all the time, but it's like, it feels like we have to be true and honest about it.

MARSALIS: I think the biggest thing for me about how a lot of us met each other, we were in white spaces, which I think is the most bizarre element of the community that we have now. I knew Gio in high school, he knew me in high school, and, we just all had these similar [experiences] — just being uncomfortable, that's really the only reason why we're all friends. We were all very uncomfortable, and we were just like, Hey, maybe if we hang out we'll be more comfortable. I feel like it's really that simple. The poetics are the poetics, but at the base of it, I trust all of you.

ESCOBAR: I think that's sort of a unique and new thing, for me at least, being in a community of like-minded people, both in our artistic dispositions to the world, but also just like our roots and family. That's a lot of what the album is about. Our lineage and why we are in the situations that we are in, where that comes from, and how it's led us to where we are now. It's funny, I was thinking about this earlier, too. I think there's something inherently political in everything we do. It's not like fun or cool to admit it, if you just think about the lineage of music we're in, all of these musics or idioms we play within, are actually just about people who sell their pain. This is what this music is all about. And [by] “sell,” meaning people buy it, but that expression, that's sort of what that looks like. That's what I meant by like-mindedness: this is the only way we know how to do this.

Photo by Devlin Claro Resetar.

Photo by Devlin Claro Resetar.

Listening to the project, it’s mad empowering, especially for black and brown kids.

It's sort of this process of bringing tension. As far as the world goes, the actual planet, tension is something that builds from underground, so earthquakes, things like that, are the creation of certain stones and rocks, it's a process of bringing tension underground to aboveground tension. Not like we're going to come to a resolution of like, why black and brown people aren't prioritized already. But that it's important that people know where we stand, and how we feel because otherwise, we would be discrediting ourselves or not being as true as we want to be. That's important to me. Not to create this escapist world, where all black and brown people are beautiful and we're equal and everything is all great, because that's not the truth. We don't make escapist music. If anything, it has more to do with absurdism. Look at everything — how can we not be reacting this way? How can we not feel we need to be closer together?

MARSALIS: I think it's important to see stuff. Seeing a brown person do something, or seeing someone that looks like me do something, is an extremely empowering thing. I feel like we all feel that way. Like Gio was saying, there's not enough of that.

ESCOBAR: To be intentional. That has to do with the imagery we like to put out, too. I think one of the biggest motifs we have is the monkey or the image of the gorilla. How typified that is to relate to people that look like us, people as monkeys — that's such a normal racist thing. How to approach that in a way that actually means something to us? There's all this King Kong-type stuff that happens on the album. King Kong was this very natural thing trying to suddenly survive in a city, and not in a safe way — it was very violent. His death is ultimately very violent. We tried to talk about that [on the album]. All of these things are intentional and connect to all of these things that are maybe not so accessible, but can only come from our experiences as black and brown people. I think these things we go through, if we don't talk about them, we're just going to be redundant, and not allow ourselves to progress.

Photo by Devlin Claro Resetar.

Photo by Devlin Claro Resetar.