My mother saves everything. She buys groceries in bulk. She swears the ketchup that expired six months ago is “still good.” She’s always prepping, planning, organizing. She has enough canned food stored, in case there’s ever a flood, storm, a drought, or a war. My mother has learned how to stay prepared, because she’s always had to be.

She was born in Santiago de Cuba in 1964, where she lived until 1970. Following the political and economic turmoil carried over from the Cuban Revolution, my family fled to Miami. They stayed there for a few months until my grandfather learned he would need a car to get around. They then left Miami for Puerto Rico where my grandfather couldn’t find work, so they finally settled in Queens, New York.

Like many immigrant families, my family came to the U.S. with hardly anything. My grandfather worked in the laundry room of the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center in Queens, and my grandmother cleaned offices in Manhattan. Together they raised three kids: my mother Solange, my aunt Mabel, and my aunt Yeseña.

Many Cuban Americans who immigrated to the United States have a hard time remembering their lives on the island. When I asked my mother what she recalls from her short time in the country, she explained: “A lot of people who immigrated here from Cuba don’t remember the people they left behind or the culture they left behind. Once you leave Cuba you forget what it was like.” And even if they did remember, Cuba is, like anywhere else, vastly different now than it was in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s.

Before the travel ban was lifted, Cuba seemed like a distant land. No one in my family had gone back since fleeing decades ago. And, because it had been cut off from the U.S. for so long, I hadn’t realized it was a place that people actually visited. Although it’s only about a hundred miles from Florida, where most of my family lives, Cuba may as well have been on another planet entirely. It was only after watching friends book flights, take pictures, and share stories about traveling to the island that it became a real place to me.

This summer, my partner and I had planned to go to the Dominican Republic to visit the other side of my family. But after our plans went sour, we decided to go to Cuba. I first imagined the trip as a sort-of homecoming. Upon arriving on the island, though, I immediately realized that though I have ties to the land, I was still a tourist. The country felt familiar, but also foreign.

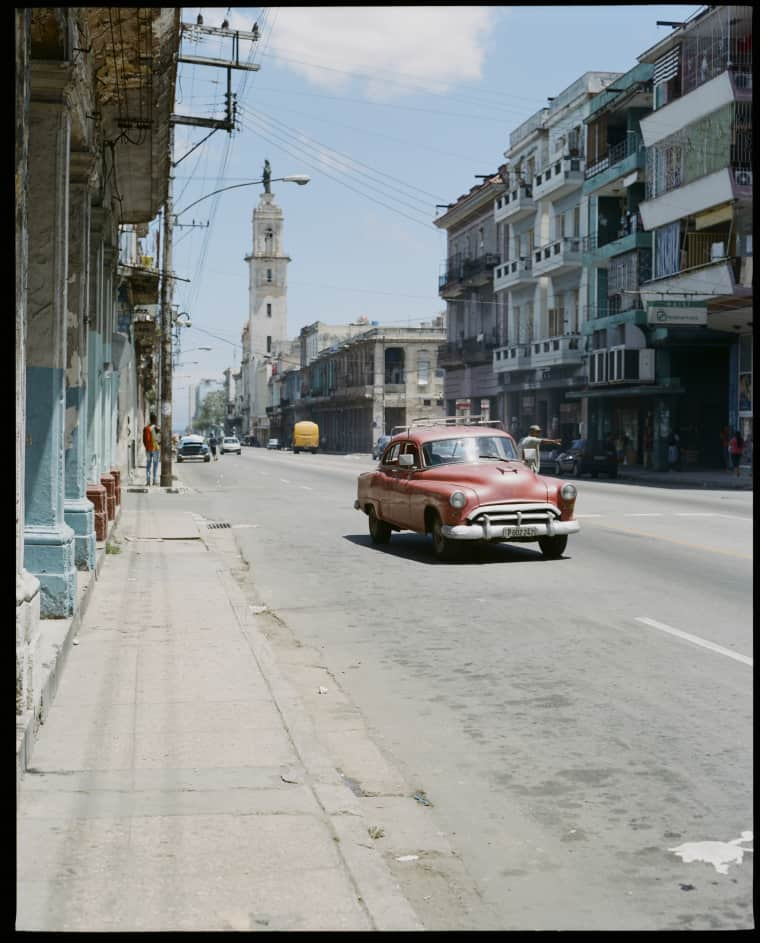

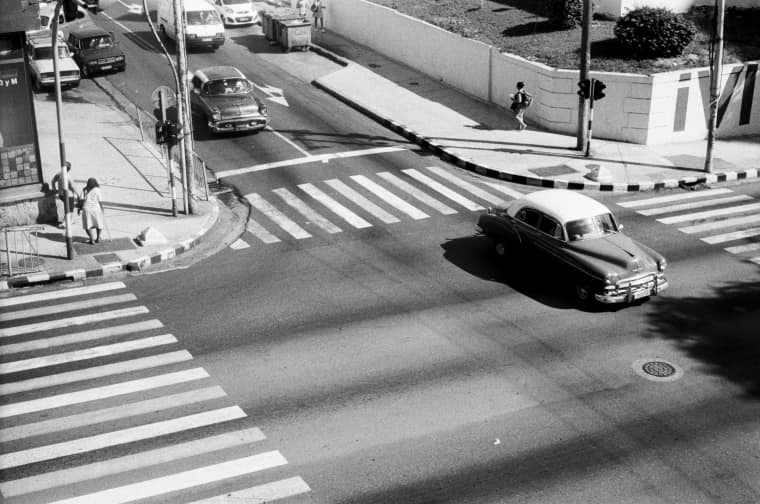

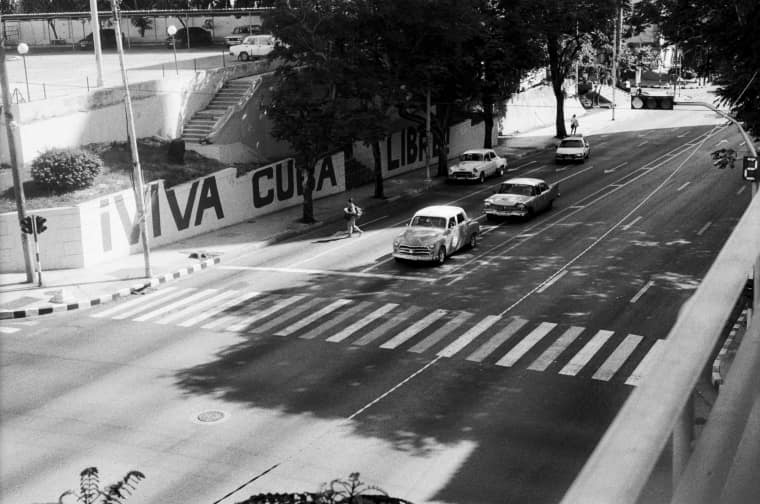

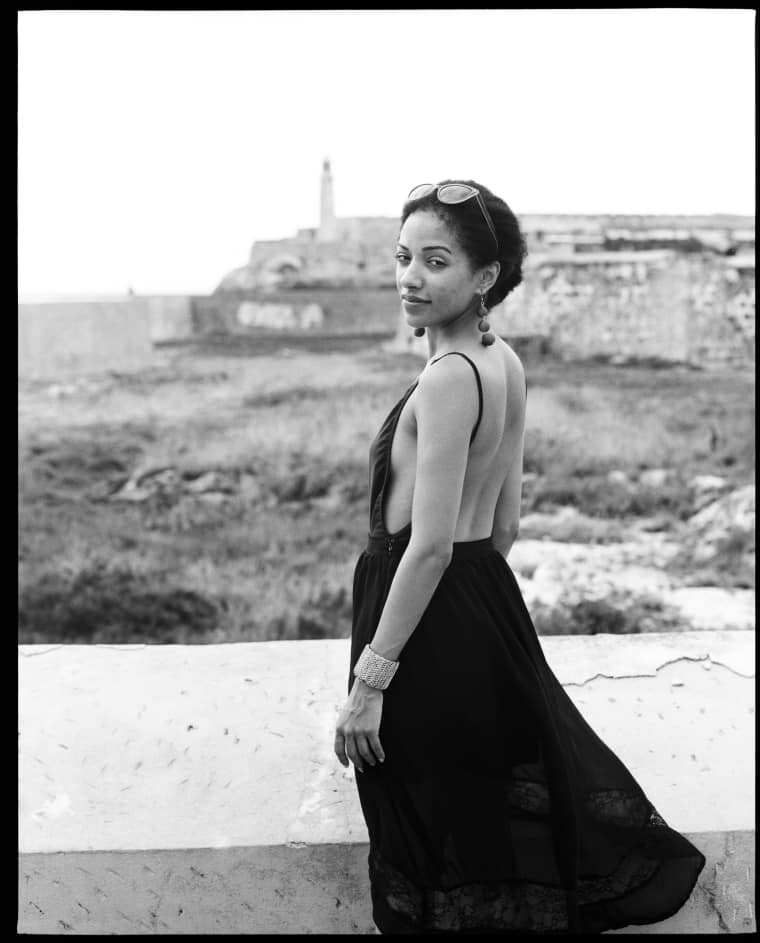

Walking through the neighborhoods in Havana on our first day in the city, I saw a Cuba that is very different from what I had seen in Instagram photos, on travel websites, and from word-of-mouth. I didn’t see a paradise, not that I expected to, but that’s how Cuba is advertised: as a mystical trip back in time. Instead, I saw a vibrant society with a painful history and harsh realities.

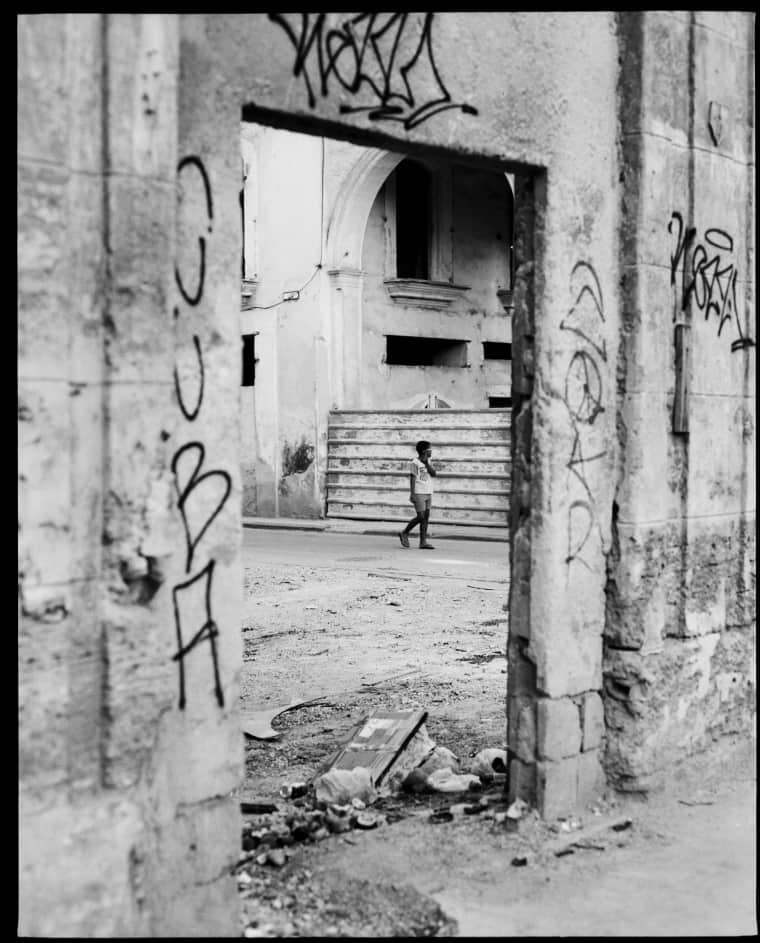

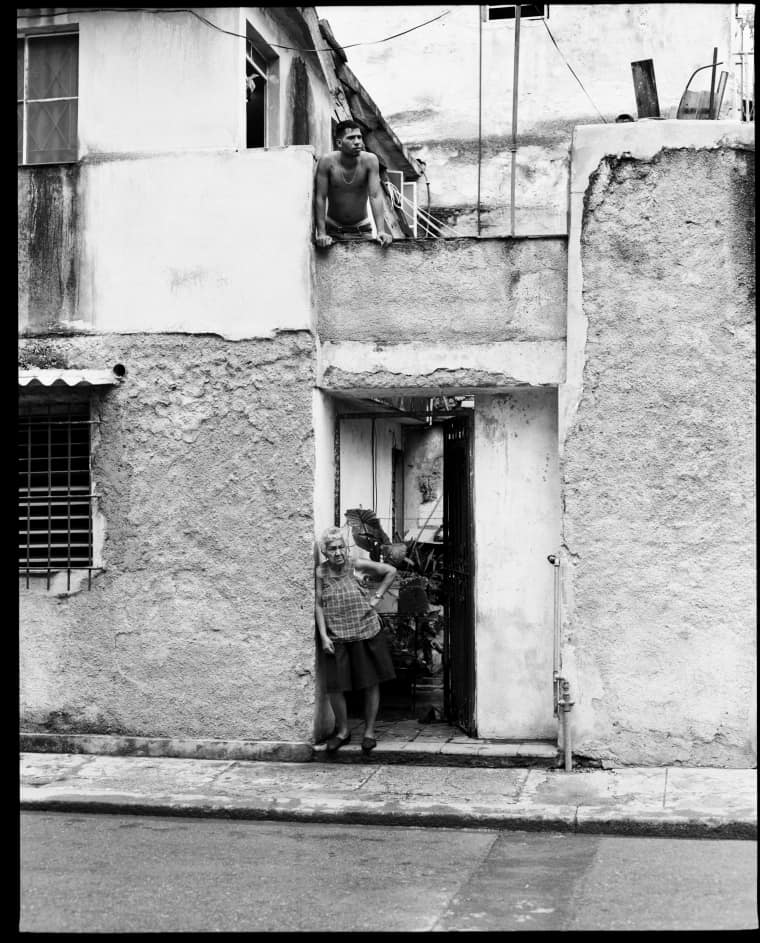

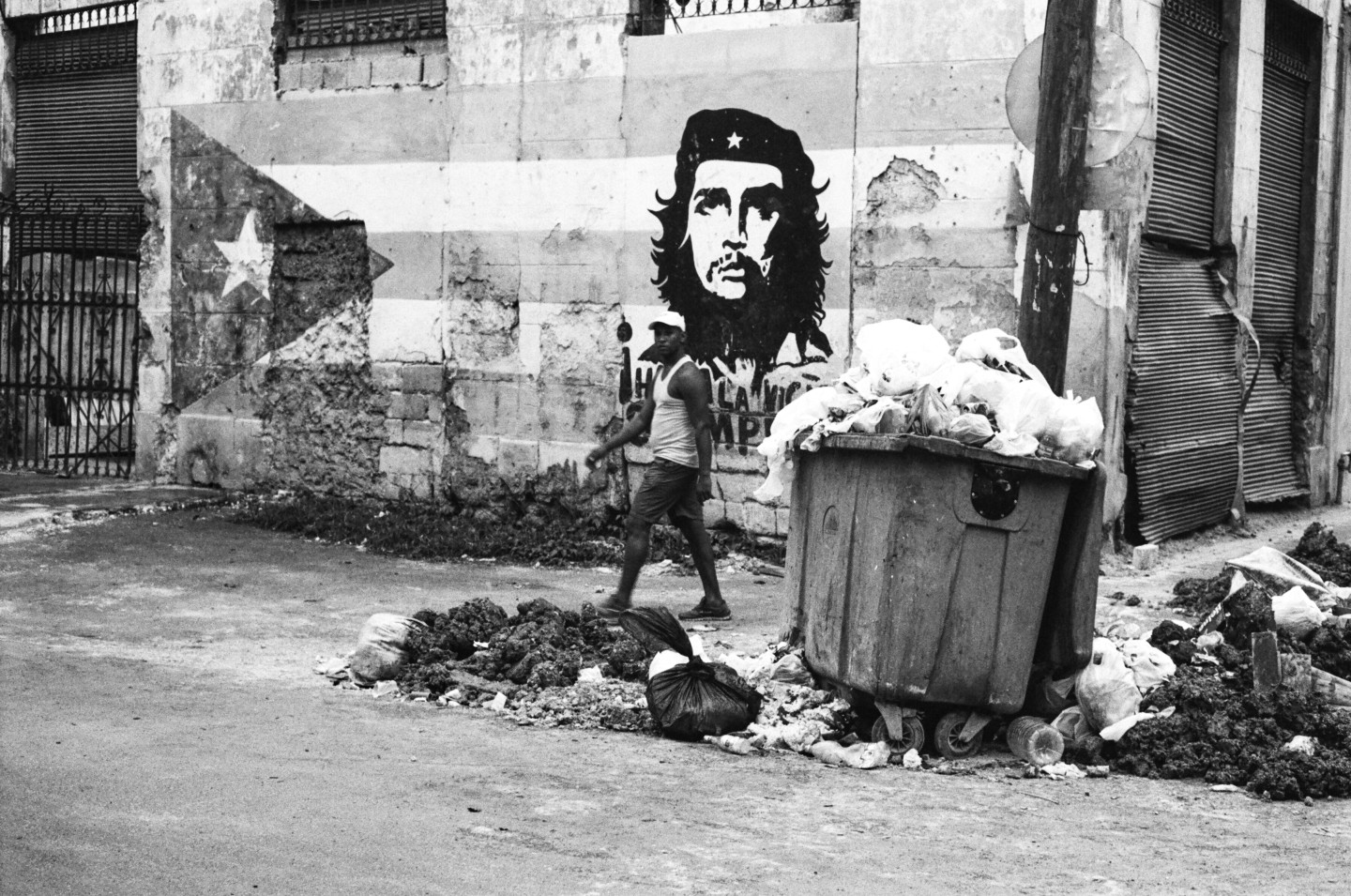

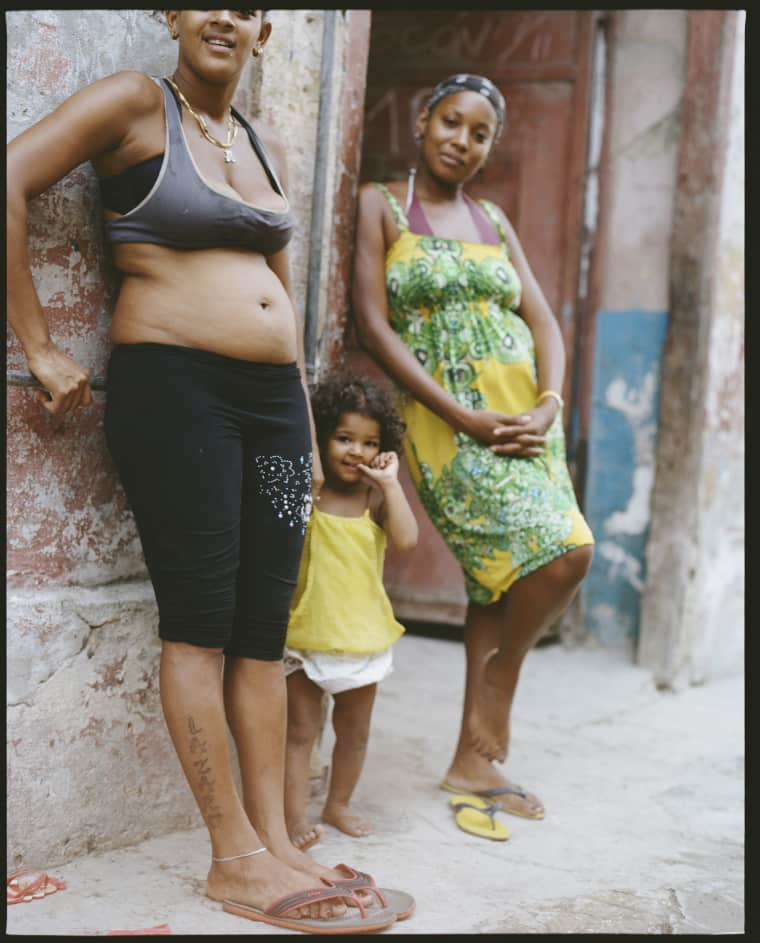

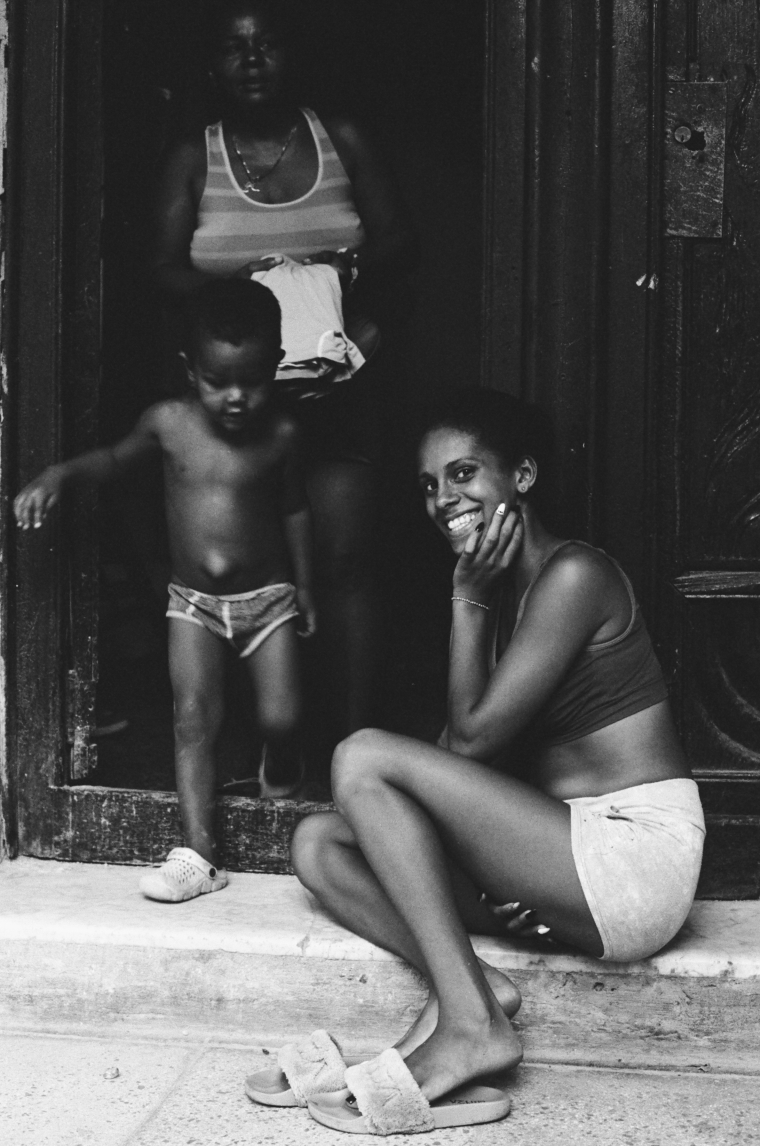

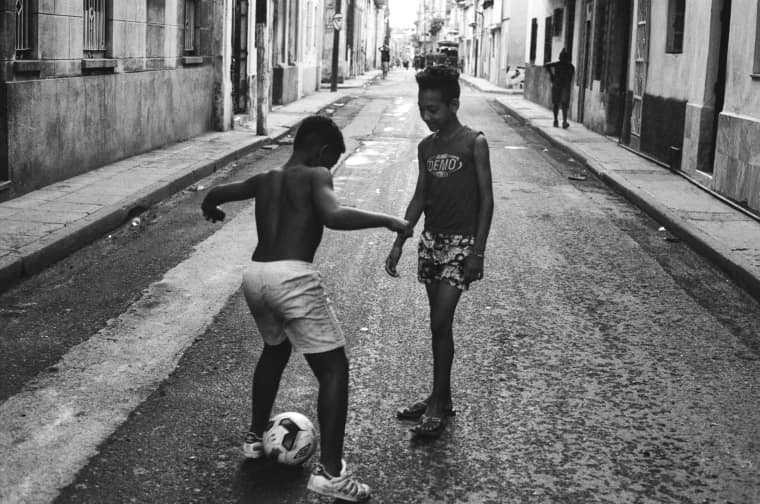

Of the Cubans we spoke to, many said similar things about what it’s like to live there. They all said some variation of, There are two Cubas: the one tourists see and the real Cuba. This was obvious in the stark contrast between the tourism industry and the rest of the country. Streets catered to tourists are clean and attractive, while residential neighborhoods have crumbling buildings and are littered with trash. While I did see a liveliness and a sense of community I’d never seen before, and felt the deep connections the people have with each other, I also saw people without all the resources they needed. I saw scarcity and hunger. A cab driver we met described the realities of living there. He said, “It’s hard to live in Cuba. The price of everything is going up, even in the countryside. I have cousins in the countryside that can’t afford necessities anymore.”

On one afternoon during our trip, my partner asked a woman in a neighborhood near Old Havana if he could take a photo of her. She agreed, and then she advised him to put away his (very large and noticeable) camera. She said, “I thought you guys were Cuban until I saw your camera. This is a violent neighborhood, you should put your camera in your bag before someone takes it.” The Cuban government, meanwhile, describes crime in Cuba as nonexistent.

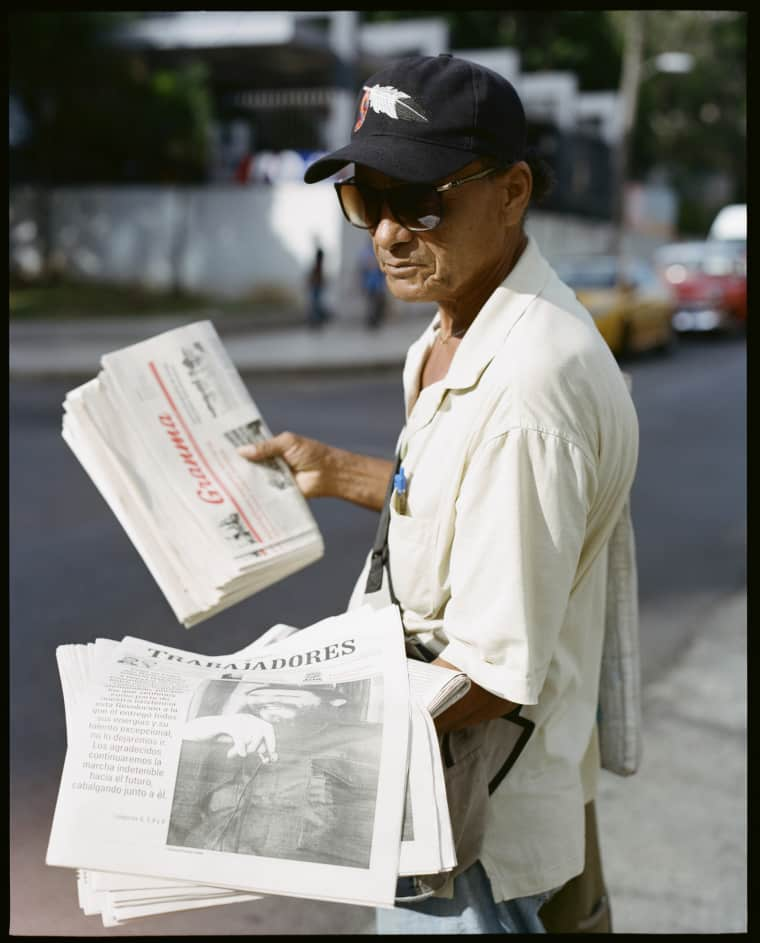

Like all countries, Cuba has had a long history with government corruption, propaganda, and power-hungry politicians. Everyone has an opinion on the island, but what is the real Cuba? Is it the egalitarian society the Castros and Cuban government say it is? Does it function as a dictatorship as the U.S. government says it does? Does its reality live up to the ideal socialist model that activists have historically described it as?

The romanticized Cuba, the Cuba that is a perfect communist society, where everyone has everything they need, and everyone is pleased with the government, is a falsity. And it only takes a few conversations with local people to see it. Obvious class differences exist in the country, fueled by the class of people working in its tourism industry, the most lucrative industry on the island. Human suffering exists everywhere, but to deny it exists in Cuba because the country has a system of governance that you theoretically admire is dismissive and dehumanizing.

Being in Havana, I got the sense that people have been describing Cuba in any way that serves their agenda or experience, but the country is far more complicated than any one definition. Ultimately, the people of Cuba are the only ones who can define the country.

I mostly thought about my mother during the trip. I thought about how she raised her two kids, my sister Desiree and I, by herself while working two jobs. I thought about how resourceful she had to be, how resourceful her parents had to be, and how resourceful Cubans and Cuban Americans have had to be. When I saw a man selling pastelitos de guava on the street in Old Havana, I thought about all of the former side hustles my mother had to juggle just to be above water. I thought about how tired she was all the time. I considered whether she’d ever found pleasure in small victories when life felt like a losing battle.

Scarcity is traumatizing, and that trauma can cause people to always plan ahead in fear of not being able to survive. Surviving is a 24/7 job when you’re constantly straddling the line between having what you need and having nothing. Things run out, things go wrong, and everything can fall apart in an instant. The panic of not knowing if you’ll have enough of what you need to survive is enough to train yourself to stay prepared.

Growing up under the care of my mother over the years, I’d always thought I was nothing like her. While in Cuba, I realized that I’ve inherited her resilience, and her ability to adapt. During the trip, my partner kept telling me, “You are your mother’s daughter.” I was prepared, and had anything we could have possibly needed on me at all times — just like my mother would be.

My mother taught me how to function in the world, and her mother taught her how to function in the world. Cuba may not be my home, but who I’ve been, who I am, and who I will become is tied to the island.

Photo by Juliana Pache

Photo by Juliana Pache

Photo by Juliana Pache

Photo by Juliana Pache