The FADER's longstanding GEN F series profiles emerging artists to know now.

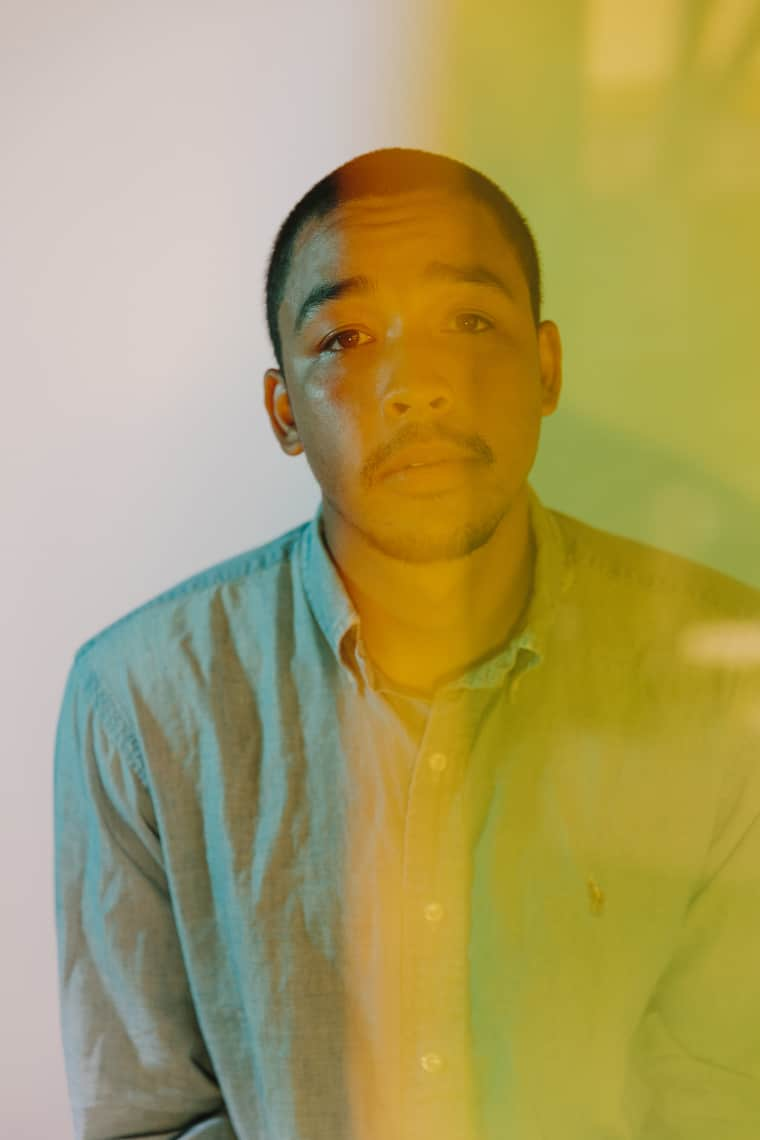

“What’s the deal with the ‘myth’ tattoo?” I ask Dijon Duenas, jutting my chin at the word inked into his muscular left biceps, inches below the cuff of a mustard-yellow Beat Happening T-shirt. “There’s just something about symbology and what I want to do — and what I hope to do — in music,” says the 26-year-old, who’s currently best known as the former vocalist of the R&B duo Abhi//Dijon. A Los Angeles breeze, limping and wheezing around Griffith Park’s walnut oaks and chaparral, kicks up; a Springer Spaniel barks. “There’s a pulling apart of American symbolism and ideas,” he continues. “Roland Barthes has a book I was reading — not to sound like a dickhead — and [there’s] a human need for these symbols and signifiers as weird, abstract representations of humanness. That’s fascinating.”

Dijon’s attempt at imposing something like order on American culture’s bricolage is understandable. His life and art are, if not fractured, constituted of bits and pieces from an empire in remarkably stupid decline. His parents met in the Army; his mother is of mixed black and white heritage, and his father’s Guamanian, with a surname that bears the burden of his native island’s Spanish colonizers. As a child, Dijon was shuttled between the United States and Germany, never in one specific city for more than a couple years.

He was often tethered to American music not by proximity, but through an internet connection. As a teenager, he’d make rudimentary, sample-chopping beats with a four-track tape recorder and FL Studio, but Dijon didn’t begin to seriously make music until his senior year at the University of Maryland, when he and former high school classmate Abhi Raju formed Abhi//Dijon. Between 2012 and 2016, they released a compilation and two EPs of pulsing, hazy, washed-out R&B, featuring Raju’s production and Dijon’s crooning.

Though they released their final EP, Montana, after moving from Maryland’s Ellicott City to Los Angeles in the summer of 2016, the five songs don’t accurately reflect the artistic shift Dijon experienced after relocating to the West Coast. “There wasn’t necessarily a reason things went solo — there was no negativity — but I think that overall I was always trying to find a way to channel shit that I was really into,” he says, referencing the literary yet pared-down stylings of Joni Mitchell, Feist, and Bill Callahan. “Once we got to Los Angeles, it just happened organically and naturally. It was pretty unspoken.”

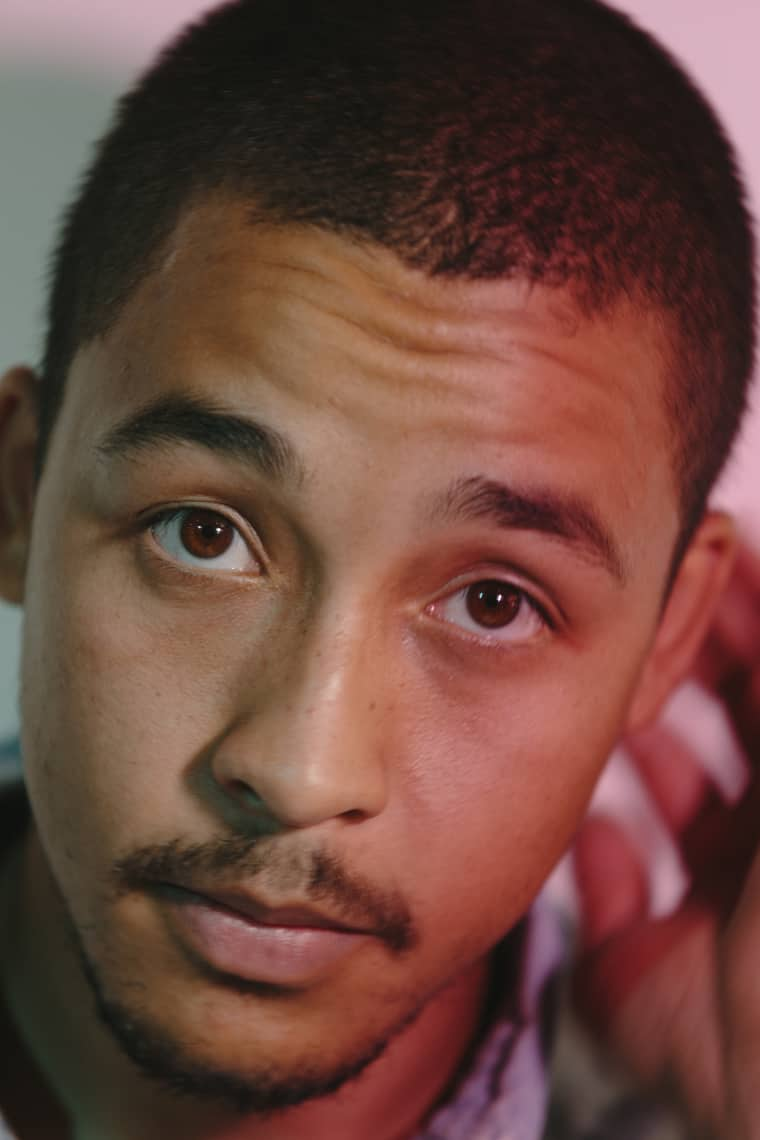

Dijon’s newest material — a series of five singles which may eventually be grouped into an EP (at press time, he was unsure of both the title and the release format) — hews closer to the faintly Western, denim-clad singer-songwriter tradition. His lyrics, which were broad in scope and scant in detail during the Abhi//Dijon period, now include the kind of narrow, hyper-specific tidbits that the writer Tim O’Brien called “story truth,” where slight fictions reveal emotions unsatisfactorily addressed by stark fact.

On the newer songs, the jaggedness of homesickness and a real-life romantic breakup is on display, but their edges are smoothed by a thin muslin veil of storytelling. Violet, the object of Dijon’s affection on “Violence,” is fictional; the titular character of “Nico’s Red Truck,” which has the strummy momentum of a campfire sing-a-long, is a “sick motherfucker” who drives a red pickup. Both tracks are meant to evoke the summertime gaiety and heartbreak of his final months in Maryland.

In writing and recording guitar-driven music, Dijon says he experiences a measure of cognitive dissonance: How does he, a person of color, translate what’s considered an implicitly white style of music? He’s still figuring it out, describing himself as being “fascinated” with the process of “really unironically and genuinely appropriating these symbols, ideas, and mythologies that aren’t necessarily associated with minority music.”

He’s learning to interrogate the simultaneously eldritch, benign, and still-resonant tropes of suburban fiction: UFOs, bandits and law men, and, as he puts it, “the singer-songwriter.” “You realize when you get older you’re not represented in those ideas or in that world.” With his solo music, he’s repurposing exclusionary Americana for his own needs: no longer fey, folksy, or quaint, but bold, sun-baked, hinged on longing and self-examination. And for Dijon, it’s no longer myth.