Ryuichi Sakamoto’s infinite spaces

Some of the richest rewards of the late Japanese composer’s legacy can be found in the places between the notes.

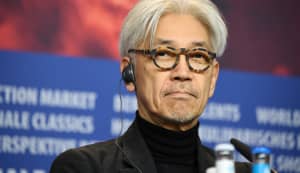

Ryuichi Sakamoto. Photo by Zakkuban

Ryuichi Sakamoto. Photo by Zakkuban

Ryuichi Sakamoto is standing next to a melting Arctic glacier, tapping finger cymbals together. His face is transformed; the wrinkles of old age become a child’s laugh lines as he absorbs the majesty of the sound, transformed by its environment. Now he’s in a destroyed auditorium in Fukushima, drawn to what he calls “the corpse of a piano” nearly destroyed by the tidal wave disaster but still dutifully creaking out notes from underneath Sakamoto’s fingers. Now he’s in his New York studio, composing music for his album async. That may not be entirely accurate: he’s searching, hunting for the perfect sound of metal, rubbing a coffee mug against a cymbal — no, that’s not quite right — and pulling a bow against a gong — is that closer? Who can say? There are questions about music that only Sakamoto thought to ask.

These scenes, taken from the 2017 documentary film Coda, are helpful to access a legacy that can seem too imposing to fully reckon with. These small moments are treasures for the insight they offer into how Sakamoto lived with sound, creating new entry points to a career of wide-spanning influence across modern music. Sakamoto helped usher in hip-hop and techno as the keyboard virtuoso and one-third of Yellow Magic Orchestra alongside Haruomi Hosono and Yukihiro Takahashi. His work as a composer on films like The Last Emperor, The Revenant, and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence earned him dozens of awards, including an Oscar and two Golden Globes. As a solo artist before and after the demise of YMO — particularly with projects like 1980’s seminal B-2 Unit — he weaved a legacy that would leave no corner of the modern electronic underground untouched.

As news of his death on Sunday spread, a deep fissure grew with it. Expressing it to adequately match his legacy felt impossible, as clumsy as asking an artist “Where do you get your ideas from?” The things that are formative in our lives don’t have a form we can grasp onto. Someone as elusive, immutable, and sincere as Sakamoto makes the task much more imposing.

That day, a reshare of an interview with Sakamoto from The Creative Independent came across my Twitter timeline. He was discussing his newer, more ambient-focused music: "I want to have less notes and more spaces. Spaces, not silence. Space is resonant, is still ringing. I want to enjoy that resonance, to hear it growing, then the next sound, and the next note or harmony can come." In my mind’s eye, I saw Sakamoto again in the documentary, drinking in the sound of the finger cymbals mixing with clear arctic air, then in Fukushima, and then back in New York City, his face in deep concentration as the ceramic mug was rubbed against the cymbal and lifted. There he was, in the space.

This is one way Sakamoto’s life can be thought of: as a series of spaces spanning near infinite directions, unified and outside of time, which we will inhabit until there is no more “we.” In a more literal sense, these spaces can be found in his music.

The one that currently gives me the deepest sense of gratitude comes during “El Mar Mediterrani,” composed by Sakamoto for the opening ceremony of the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. A just-over 17-minute composition, it is the soundtrack of a Pandora’s Box of human endeavor being opened. The avant-garde classical opus is driving, even cinematic in its opening, its strings and piano achieving a runner’s high with their pace and energy.

Then the movement ends, and the piece jumps back and forth between high anxiety and pure chaos, hands smashed against piano keys and the dissonant, zombified moans of the surrounding instruments. “El Mar Mediterrani” contains the relentless drive that fuels both great accomplishments and untold, incomprehensible suffering (it’s also visualized in the actual performance, a superficially swashbuckling battle of ships on a sea of blue gowns surrounded by rusty deforestation machines, hungry vultures, and enormous switchblades). It’s a subversive work in how it channels our hunger for growth and success — a quality inhabited by the Olympics themselves, an event that frequently leaves chosen cities in debt and disarray — and places it at the forefront of the 1992 games.

Much of the music is gripped with the tension of a fierce reckoning, until the 13th minute, where the space I have found new comfort in begins. The caterwaul gives way to something like whalesong, inquisitive and peaceful. It’s a brief transition, and the orchestra returns for the finale: an ascendent near-waltz, a delicately ecstatic communion that is triumphant, and honest in that triumph, with how the melody seems to bear such deep wounds from its battles. Inside this particular space, Sakamoto says, lies the heart of a story with no ending or beginning. Something redemptive, something complicated, and something eternal.