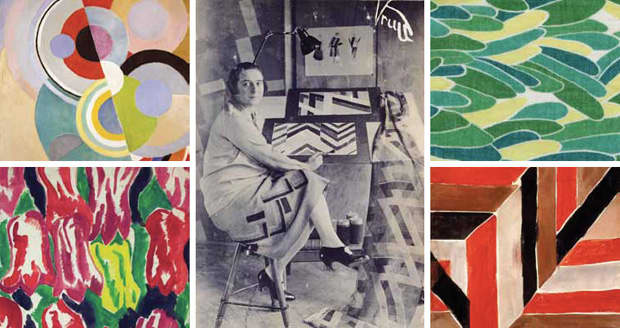

A retrospective of Sonia Delaunay’s textile and design work will open this spring at The Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum, marking the first time in 30 years that her efforts, including paintings, garments, illustrations and letters, have been gathered and shared in the United States.

Matilda McQuaid, the curator of Color Moves, poses Delaunay as one of the first artists to live her work holistically. As an extension of her abstract and painted pieces, Delaunay eventually made a career out of translating her vision to clothing, but she never described herself as a fashion designer, as a feminist, or even as a woman in any certain way. She knew herself only as an artist. Her abundance was propelled by a terrific need to express herself, a force we recognize as the root of modern art.

Born in Ukraine, Delaunay moved to Paris when she was 19. She married her gay best friend so that she could stay as a resident. It was a marriage of convenience but they shared a strange love and studied African and Egyptian art until she met Robert Delaunay and married him. They became painters together, arranging shapes to provoke rhythm from the simultaneous contrast of certain colors. They painted in order to understand what occurs when human eyes encounter a color-saturated world, and how color values come to blush our minds and lives, a phenomenon they named “Simultaneity.”

The First World War left the couple, who now had a small child, exiled in Portugal and newly unstable. Having lost her family’s main source of income, color, the theme of Sonia’s life, became her business. She began to combine the tones of the Basque countryside, familiar Russian folk crafts, and the poems of her dada friends into a new visual language. She made a patterned patchwork blanket so her baby could rest in radiance and when her husband saw it he made one of the first art-collages.

They returned to Paris, and Robert remained consumed by the theoretical underpinnings of his painting practice. In contrast, Sonia was evolving as a doer and not a talker. She filled their apartment with visitors and her designs—lamps, curtains and neon sculptures. That extravaganza was amplified in the boutique she staged inside a larger fashion house, where she dressed a modern elite in loosely draped fantasies of geometric patterns and appliquéd furs.

Despite Robert’s inability to support his family financially, Robert and Sonia’s relationship was ultimately a great synergy. The luxury goods she created for private clients promoted Robert’s theories and his ideas endowed Sonia’s designs with higher status. Nevertheless, Delaunay did not become a successful fashion designer, perhaps because she never bothered to manufacture clothes on a large scale, or treat them less personally than other compositions.

It didn’t worry Delaunay that her work would be tainted by commerce. She considered the textile designs used for interiors, scarves and ties that became her major output as significant as her paintings and gowns. She became a cult hero because she welcomed all of those as unique and valuable challenges. Unlike Frank Lloyd Wright and members of the Bauhaus, whose designs displayed a union of form and function, she did not expect her objects to create a simpler, more perfect world. Color Moves reflects this fact and aims to protect Delaunay’s “more is more” aesthetic.

Delaunay worked until she reached 90 and said then that she had lived three lives: a first for her husband, a second for her children and a final one for herself. Color Moves has shades of only the first. The taste is still thrilling, providing a foundation for visitors to imagine how they might ripen into their own worlds, doggedly forcing the look of their art and life together, finding and creating elegance in all things.