Jessamyn Fiore’s new book revisits a pioneering art space.

Jessamyn Fiore’s new book revisits a pioneering art space.

The artists that emerged from New York’s avant-garde scene in the 1970s often talk about SoHo before it was SoHo: a burned-out low rent district with ample loft space to house like minds. In addition to living, playing and performing in these spaces, this neighborhood was also a breeding ground for new forms of exhibition spaces, 112 Greene Street being among the most progressive. In a new book, 112 Greene St, published by Radius Books in conjunction with the gallery show 112 Greene Street: The Early Years (1970-1974), which exhibited at David Zwirner last year, curator Jessamyn Fiore presents a compilation of interviews conducted between June 2010 and January 2011 with 19 artists, performers, organizers, writers and friends who were involved with the space. Fiore explains in her foreword:

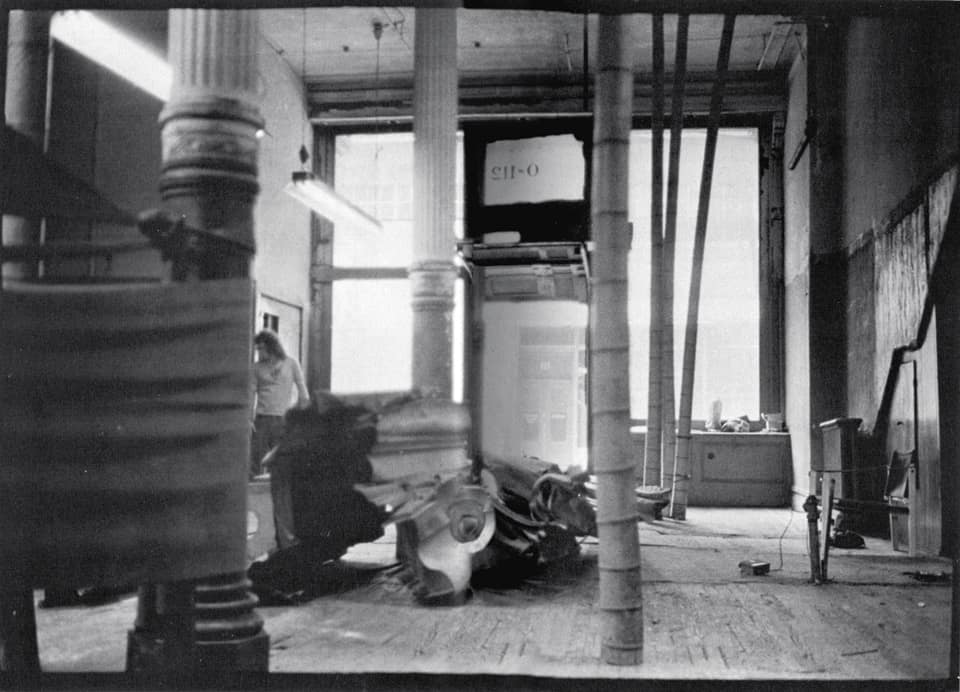

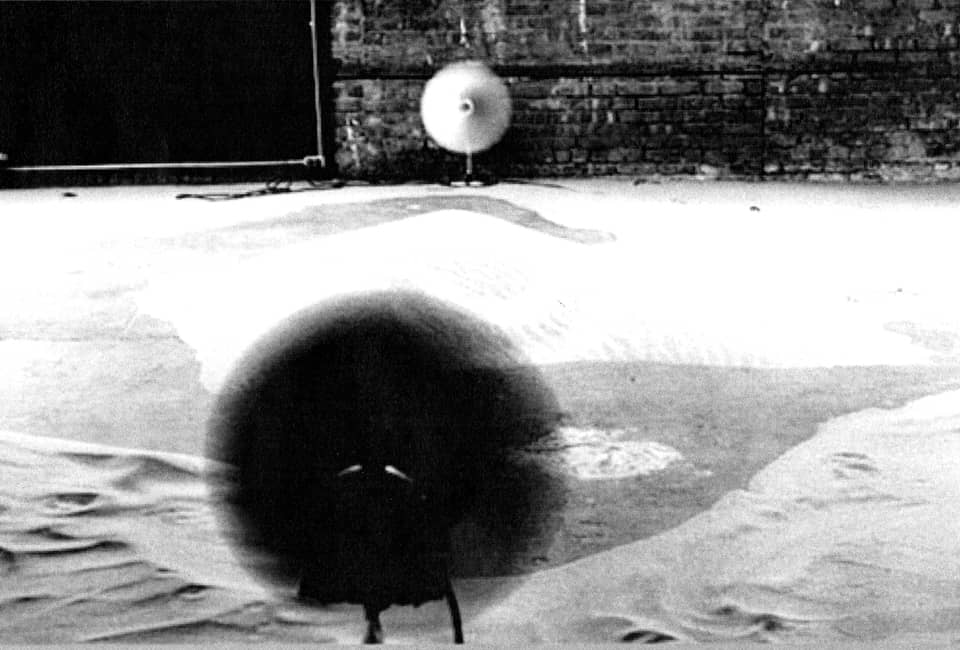

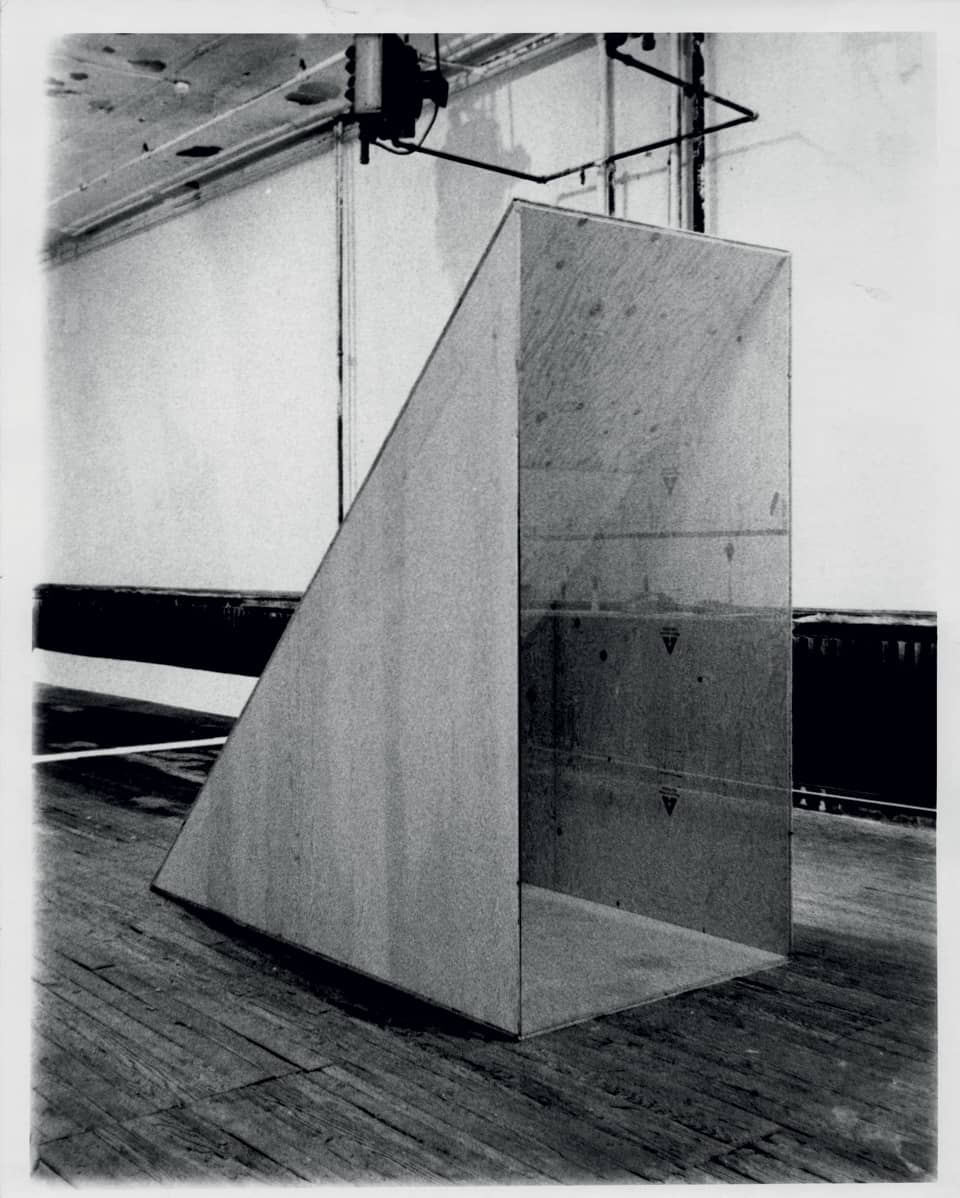

Opened in October 1970 by Jeffrey Lew (with Alan Saret and Gordon Matta-Clark), 112 Greene Street became the first sizeable, independent art space in New York that resisted calling itself a “gallery.” A place for artists to both create and exhibit works, it was self-curated, and during its early years, did not have a formalized committee for determining exhibition schedules, sales strategies, and fundraising. Celebrating organic and some-times anarchic qualities, Lew ran the space with his friends—as an artist, for artists—never refusing anyone the freedom to dig a hole in the basement or cut into the walls. 112 Greene Street became the center of the community. It encouraged interdisciplinary cross-pollination, effectively blurring the boundaries between the visual and performing arts.

The later years of 112 Greene Street saw Lew struggling with the bureaucratic demands of grant funding, and the space was threatened with closure several times. In 1976, Lew relinquished control of the building and took over the basement to create the Big Apple Recording Studio. 112 Greene Street almost shut down entirely, but rallying support from the artist community kept it alive, perhaps most notably when Philip Glass threw a benefit concert at New York University in March 1977, for which James Rosenquist designed a limited-edition poster. In 1978, the venue split from its namesake building and, after a brief spell at the Port Authority, opened in February 1979 on 325 Spring Street under the new name White Columns. Today, the new space is located on 320 West 13th Street, and continues its mission as a not-for-profit art space under the auspice of artist and curator Matthew Higgs. Adapting to the current artistic and cultural landscape, it exists as a vestige of 112 Greene Street, which was most certainly a venue embodying its own place and time. Despite the fact that 112 Greene Street’s existence barely spanned a full decade, Fiore explains, “its impact on a host of other alternative exhibition spaces and organizations is indisputable.”