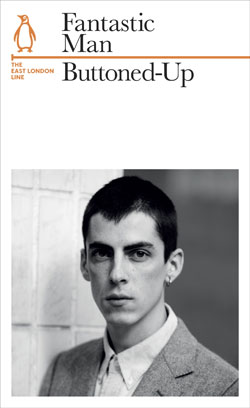

Fantastic Man is an exquisite menswear semi-annual founded by Gert Jonkers and Jop van Bennekom of the recently retired BUTT Magazine. In a new pocket-sized book called Buttoned-Up, out in England from Penguin, they trace the rebellious history behind men's use of the top button, particularly a certain kind of puckish gentleman who buttons his Oxford all the way up to the neck, a look we fully support but didn't know had a story significant enough to be written about. FM traces the buttoned collar sans-tie to its roots in the music and pub scene of East London, where, the constricting look is said to be unusually common, cemented by post-punk bands like Orange Juice and The Jesus & Mary Chain. The book contains an interview with Neil Tennant of Pet Shop Boys, a think-piece by Simon Reynolds and an essay by Paul Flynn, detailing Veronica Falls drummer Patrick Doyle's story about how he got interested in buttoning his shirt all the way up to the top. Read an excerpt from Flynn's piece below, and buy the book here.

Patrick’s school uniform in rural Scotland was a white shirt and V-neck jumper, no tie. He says the boys would wear their shirts one button open and the girls maybe one more. Just teenagers, loosening up. When he was sixteen he happened upon a picture in a magazine of Orange Juice guitarist James Kirk. ‘He was holding his guitar and he had a really long trench coat and a bowl cut,’ says Patrick. ‘He had his shirt buttoned up. I thought he looked like the coolest person in the world.’ Prompted by this revelation, Patrick decided in a small moment of schoolboy rebellion to follow his lead.

[caption id="attachment_247360" align="alignleft" width="225" caption="Photography by Benjamin Alexander Huseby"] [/caption]This was his first personal styling decision, inspired by a whimsical Glasgow pop group nobody could guess the reach of at the time. Orange Juice’s deftly amateurish fusing of black groove with white noise, not to mention their charity-shop chic, would set a template for

[/caption]This was his first personal styling decision, inspired by a whimsical Glasgow pop group nobody could guess the reach of at the time. Orange Juice’s deftly amateurish fusing of black groove with white noise, not to mention their charity-shop chic, would set a template for

the future sound and look of bands who were interested in any of the crossover points on the tangent between wee small hours disco and college rock.

Whenever he buttoned up like James Kirk, Patrick felt nice. ‘At school I thought I was a lot cooler than everyone else.’ Given his unusual key visual references – he also mentions The Go-Betweens and The Jesus and Mary Chain – he probably was. ‘I guess it was my way of asserting difference.’

Last summer, I wandered with my brother Peter up the regulation East End pathway, from Whitechapel through Columbia Road, on to Hackney Road, winding through back- street Haggerston estates through to Kingsland Road and ending up in Dalston. My brother was of the age and inclination to listen to those musicians in his bedroom and watch them play the first time round. We stopped and took the temperature of this strictly self-regulated new Metropolitan runway. A lot of boys looked

like they might’ve had their lives changed by a picture of a pasty ’80s musician. ‘Everyone looks like they are going to Devilles,’ Peter suggested.

Devilles was one of a small selection of Manchester nightclubs in the early to mid-’80s that housed an angsty, interior youth subset that would peak and swiftly implode after the NME magazine C86 compilation dropped. It smelt of Breaker lager, Benson & Hedges cigarettes and early adult anxiety. The DJ sported a quiff just like Tintin. The patrons of Devilles coupled a bracing Northern humour born out of boredom with poetically abject thought. The soundtrack of this mating ground was winsome independent rock and New York City street funk, tied together only by sharing the noisy distinction of being made on a shoestring budget. It was one of those places that was driven by teenage difference; whose visual undercurrent said ‘we might not have as much money as you but we have got better ideas,’ cocking a snook at the emerging, blousy wine- bar scene in the city. Everyone in Devilles in 1985 was buttoned up.

Devilles was one of a small selection of Manchester nightclubs in the early to mid-’80s that housed an angsty, interior youth subset that would peak and swiftly implode after the NME magazine C86 compilation dropped. It smelt of Breaker lager, Benson & Hedges cigarettes and early adult anxiety. The DJ sported a quiff just like Tintin. The patrons of Devilles coupled a bracing Northern humour born out of boredom with poetically abject thought. The soundtrack of this mating ground was winsome independent rock and New York City street funk, tied together only by sharing the noisy distinction of being made on a shoestring budget. It was one of those places that was driven by teenage difference; whose visual undercurrent said ‘we might not have as much money as you but we have got better ideas,’ cocking a snook at the emerging, blousy wine- bar scene in the city. Everyone in Devilles in 1985 was buttoned up.

Almost three decades later, Patrick is one of those faces that you find dotted about the East End, who brightens the social landscape with a similar dismissal for corporate culture to folks in ’80s Manchester. He shares more with his native predecessors in Scotland and the North of England than a penchant for fastening his shirt at the collar, that wilful style act of self-strangulation. He is the drummer in a band called Veronica Falls who continue the emotional lineage of matching cheap music to exquisite thought. It is a band that leaves the tendons of its intention exposed and unpolished. Patrick gives off the primary air of not giving a fuck whether Veronica Falls makes a penny from what they are doing beyond funding the next night out. He has served counter shifts at the amusingly diffident pub the Nelson’s Head, housed behind the Costcutter on Hackney Road, to make rent between tours. Veronica Falls will never be Coldplay in the way Orange Juice would never be U2. Some people don’t want that.

He always buttons up on stage; a nod to his ramshackle heroes and forebears. ‘If I ever see a picture of myself playing, and for some reason I’ve unbuttoned my top button, I always feel a bit angry at myself,’ he says, ‘I feel it makes a big difference to the way you wear

a shirt. It’s really subtle but it changes an entire outfit. If I’m not buttoned up it feels a bit like something’s missing, like I’ve not finished getting dressed.’

Once, on a date, someone asked Patrick to unbutton his shirt. ‘I remember being shocked because I didn’t even think of it as being weird. They made a comment about me trying to give off the impression that I was unobtainable, or really strait-laced.’

And did he honour the request? ‘No.’