The 76-year-old 'Krautrock' legend on making music with dictaphones and his seminal solo albums, reissued this week

When Holger Czukay began work on Der Osten Ist Rot in 1982, it had been five years since he left Can. Czukay formed the band in 1968 in Cologne, Germany with Irmin Schmidt—a fellow pupil of the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen—helping forge Can's reputation for groove-heavy collective improvisation and daring studio experimentalism with his bass-playing and technological curiosity. As part of the so-called 'krautrock' movement, they infused rock with jazz, contemporary classical, and Eastern elements which would go on to inspire those in the know for decades. Look at their influence today: Kanye took the melody from their 1972 "Sing Swan Song" for his Graduation track "Drunk and Hot Girls" and New York grunge rock band DIIV is quick to name check them as a key inspiration for their songwriting style. As evidenced by his praise of his consumer-grade dictaphone in our interview below, Czukay was always fascinated by tape manipulation and dabbled with primitive, tape-based sampling techniques throughout his career, making musical use out of found sound long before devices like Akai's MPC line made such practice easy. Canaxis 5, his 1969 record with Rolf Dammers as Technical Space Composer's Crew, is a cogent and early articulation of his tape innovations, a true companion and predecessor to his post-Can solo records.

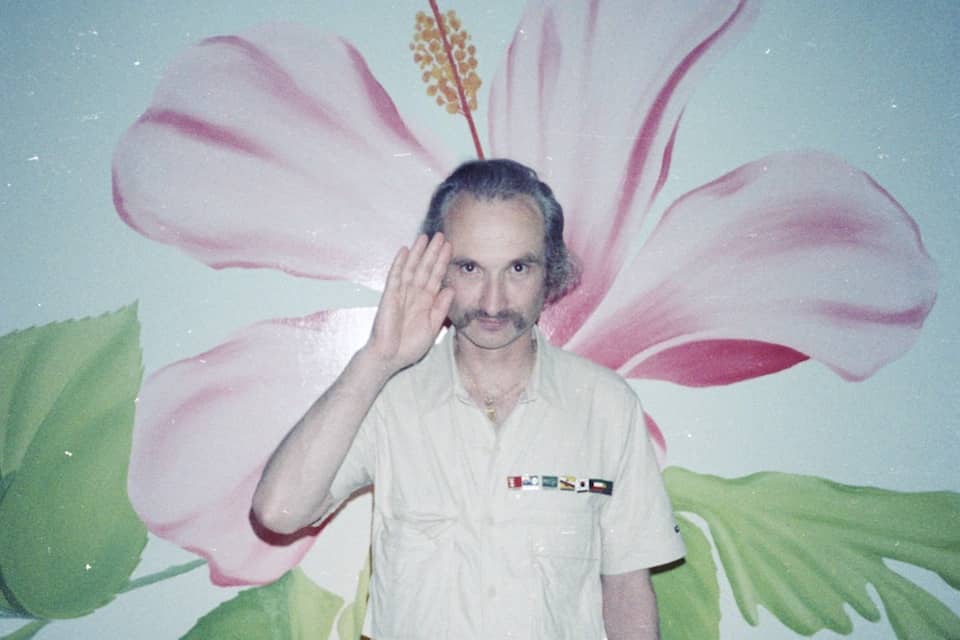

The two records discussed here, Der Osten Ist Rot and Rome Remains Rome (released in 1987), were recorded at Can's famed Inner Space Studio with Can's ex-drummer Jaki Leibniz and maverick producer Conny Plank, here contributing synth work (that's Plank's photo of Czukay from 1983 above, too). They are documents of an especially fruitful moment in Czukay's carreer that saw him devising radically new—and, to this day, bizarre—electronic musical forms within a ideologically leftist framework which informed a compositional process that erased cultural and political barriers through studio juxtapositions. In the case of the title track, "Der Osten Ist Rot"—the German translation for the Chinese Maoist anthem, “The East Is Red"—this meant reinterpreting the original to discover the link between China's heritage and communist regime. In another of the album's highlights, recounted below, Czukay and his cohorts attempted to supplant themselves into the Vatican's Easter ceremony (in spirit, at least).

Holger Czukay opened up our conversation with an extended riff on how 'The FADER' sounded like the name of some radio drama supervillain, but he was just as quick with solemn proclamations like "War time, now that was a very different time..." At a young age, Czukay learned the stakes of political turmoil. As a boy during World War II, he and his mother were forced out of their hometown of Danzig, Poland. A lucky opening on a military train to Berlin in January, 1945 kept them off the MV Wilhelm Gustloff, a ship soon sunk by the British. In adult life, Czukay is rarely one to preach political agenda like, say, John Lennon, but there are perpetual allusions to his leftism. Can has long been rumored to stand for 'Communism, Anarchy, Nihlism' and this week's combined reissue of Der Osten Ist Rot and Rome Remains Rome by Grönland Records doubles as a compendium of Europe's political concerns in the modern age. Czukay presents late-era communism with the aforementioned “Der Osten Ist Rot." He touches on National Socialism and Fascism with “Sudetenland,” recalling the piece of the Rhine Valley that Western European nations conceded to Hitler. He even hints at utopianism with “Esperanto Socialiste,” which alludes to a so-called “universal language” developed by Polish physician L.L. Zamenhof in the late 1800s, intended to unify disparate cultures. Both Hitler and Stalin viewed the Esperanto language and Zamenhof's vision for it as a threat to their totalitarian regimes.

Could you recount the process behind Der Osten Ist Rot and Rome Remains Rome? It was made in here in the studio, in the former Can studio. It was one of the greatest times [creatively] I ever faced. Can was gone, they separated. Everyone went to do their own projects. Jaki Liebezeit and myself, we remained here in the studio. We had time—not really so much happened—but we had time to explore something which we hadn't found before. It was a wonderful thing to make Der Osten Ist Rot. I had bought a dictaphone from IBM, it was from the '50s. It was, [in the '50s], a really technically forward device. I found out that this dictaphone was a perfect musical instrument, because [there were so many possibilities] of what it could be. The quality of the recordings did match the source's sound quality [in a way] that you would never expect. It maintains the recordings in the highest fidelity.

Jaki was here [working on] the strings and piano, and I went out to search out [sound] for this dictaphone, which I got for $14. Jaki played the piano and had all these harmonies and figures, and I had time to accompany him with a dictaphone, and we continued like that. [The studio] could become a café, for example, and we don't need to go [conduct and record] the concert [at a café] for something like that. You have a dictaphone player working together [with the piano player in the studio] to create something that was never before. This is how this album came into existence.

"I found out that this dictaphone was a perfect musical instrument, because there were so many possibilities of what it could be."

It seems like your solo albums and Technical Space Composers Crew's Canaxis 5 are of the same feather, so to speak. Is there a link between this earlier and later work? At that time with the Technical Space Performer's Crew, it was something that nobody had sought. Music from a certain country always has its own laws. So never would you think that someone on the fields in Vietnam could be accompanied [via studio processes] by a European player, that this would make sense, and that it would touch people in such a way. For me it was also a big, big surprise. I had to use the Stockhausen studio, because it was the only place I could do something like that. I had to use it because it had [the technology that allowed us to] play with, for example, tape speed. I had a key to enter Stockhausen's studio, so that after he left we would take over. We would have four hours for the Technical Space Composer's Crew. I never told him, I told him everything, but this I never told him this.

How did you develop your sampling techniques to make these solo records? The sampling technique was really at the beginning at that time. We tested out which syllable would this [dictaphone] understand best, and reproduce best. That syllable was “dum.” Dumm is German for stupid. It's funny that this is what the machine understood best. We worked out that the syllable was “dum” and made a new piece saying the syllable “dum.” We all had a lot of creative time and not thinking of the record company. We just had to look which we hadn't experienced before. Pure exploration. We never really felt the pressure of making money.

Do you mean that Virgin Records wasn't concerned with the financial viability of these records? That was our contract. 'Do what you want,' they said. 'It ends when the work is finished.' That's how we did it. 'We're always releasing what you're working on, and it comes out of our planned budget,' they said. It was the agreement, how we were handling our contract and music and so on, you understand, as 'contract' means agreement.

Could you describe a situation on the album in which that freedom allowed you to explore you play with ideological material? The Pope [John Paul II] was giving a sermon in Rome on Easter. I could see Easter on television, and how the Vatican was celebrating Easter, ceremony-wise. And I thought, 'This is really interesting. I think the Pope needs our help!' [laughs] Because he was looking good, and he has a Polish sense for rhythm. Very important, but he doesn't care! He needs a good band behind him. And we can help. When you hear ["Blessed Easter"] you think, 'It can't be true, that the Pope is being accompanied by a band!' And not a band which was in Rome, no no no. So I brought myself in as a musician, bringing together the crowd. How [can you] participate as a musician? For example with a string quartet, how would the string quartet play [in this situation]? You want to participate like a string quartet, but what is the language of today, the language you are able to participate in? How can you do it without this channel, without these string quartet musicians? This was always very much of interest to me.