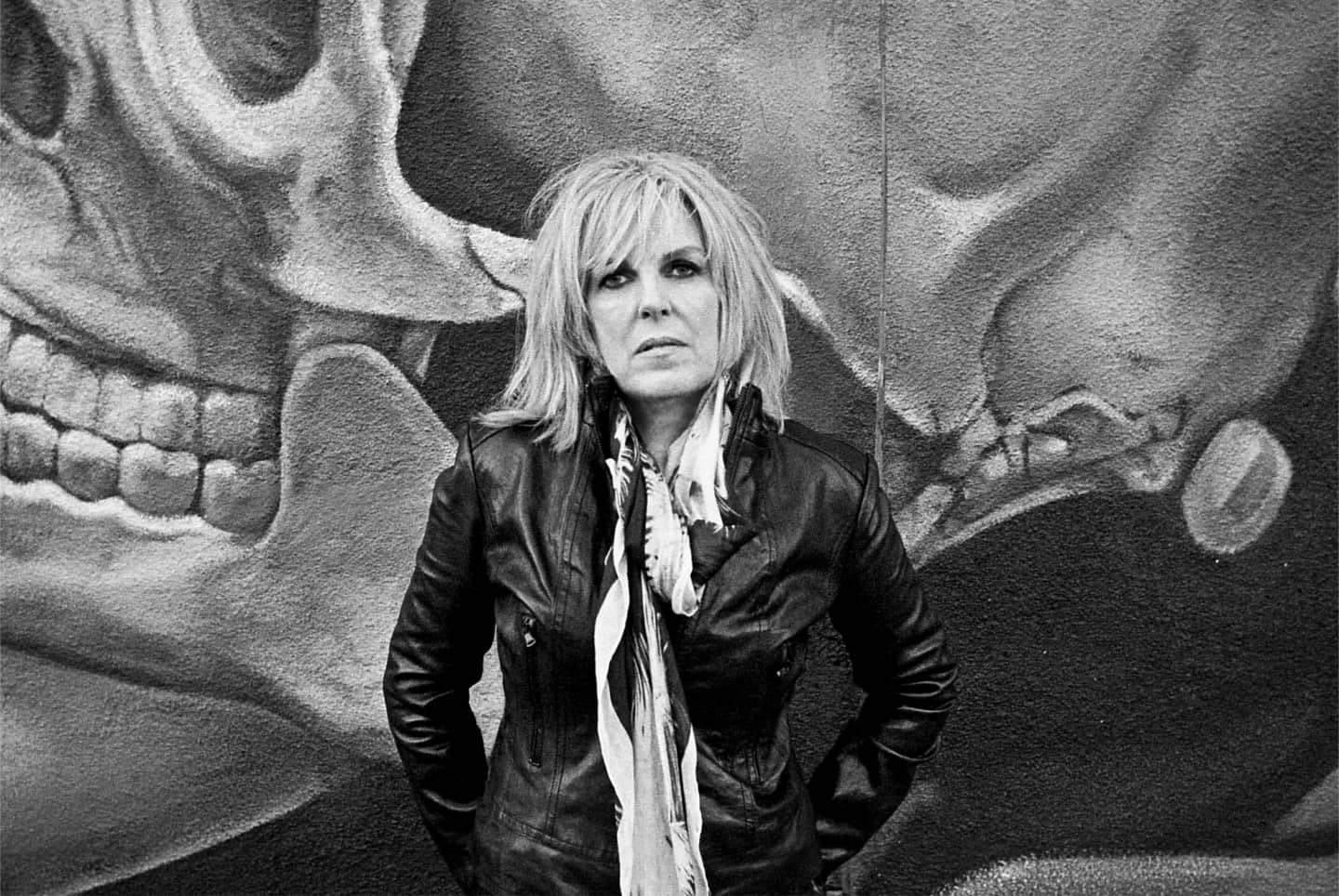

Lucinda Williams Talks Adele, Connie Britton, and Getting Older While Feeling Better

A candid Another Country interview with the American(a) icon, who has just released her 12th album and is already recording its followup.

Every other Thursday, in his new column Another Country, Duncan Cooper showcases country, folk and bluegrass music that's so often unsung around these parts, with an emphasis on new approaches to old American classics.

In the same way people have their favorite Lucinda Williams song, I’d bet most remember the song of hers they heard first, too. Mine was the opener of her self-titled Rough Trade LP, which came out when I was a baby but found its way to me much later, when I was, for better or not, more susceptible to songs about desperation in love. Rarely do two lines of “I Just Wanted to See You So Bad” pass without her repeating the title, turning the screw, turning the screw. This year, Lucinda Williams started her own label and released her 12th album, Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone, which maintains her piercing approach to songwriting among a sweet-and-fierce style she now calls, rightly, "country soul." We spoke about her father, her fondness for Adele and Connie Britton, and getting older and getting better over time.

So what set you off on making a double album? Basically, because we had so many great tracks. We recorded about 30 tracks of material, and it was pretty clear at that point that it was going to be pretty impossible to narrow it down. We decided to do a double album because we could. Creatively we had a lot more freedom this time around, since I have my own label now and everything.

Why did you start the label? It just had to do with timing. My Blessed album was my last album for Lost Highway, so my contract was up with them, and Lost Highway said goodbye anyway, so they were no longer. We started shopping around for a new label. Thirty Tigers was the first one we talked to who we immediately felt good about. It was pretty much a no brainer. We were going to be able to have our own label with them, under the offices of Thirty Tiger, so it’s like the best of both worlds. This is how you can do it without having to be completely on your own. Because nobody wants to have to do all the distribution and all of that. You want to have that in-house. That’s where Thirty Tigers comes in. I get to have my own label and have total creative freedom, and they gave us a decent advance to record with. It’s like, what’s not to love?

For those 30 tracks you recorded, what inspired that creative burst? I didn’t think you were always so prolific. Well, I had about three years to come up with a bunch of songs. I’ve been on a prolific roll over the last several years. It’s hard to explain why exactly. I think it’s a combination of things. Some of the tracks weren’t mine—I did some covers like the JJ Cale song. We did a Lou Reed cover of “Pale Blue Eyes,” a Bruce Springsteen song called “Factory.” Some of those are on the next release. We have a bunch of songs and basic tracks already cut for the next album. [Editor’s note: !!!]

Were there areas of the new album where you were challenging yourself, or that challenged you? I wanted to try to get more up-tempo songs or whatever you want to call it. That’s always been more of a challenge for me than certain other artists. I’m always saying, “Oh I wish I could come up with more Tom Petty-type songs, like the really good rock songs.” Dan Penn, FAME studios, all those old country soul songs, you know, I always listen to of course over the years, but I kind of just found myself in the mood for that kind of style, that kind of country soul. Tony Joe White Dusty in Memphis.

The first song I wrote kind of like that was “Protection.” I went to see this guy who had written or co-written some of the songs that were on the Adele album. One of them was “Rumor Has It.” And I loved that Adele album. I was real impressed by how authentic it sounded for that style of music and the fact that it was being played on the radio. I couldn’t believe I actually liked something that was on commercial radio. I liked the way it was produced and I was impressed with her voice and the writing and the whole thing. At this show, he was playing by himself—just guitar and voice. He played that song, and I’m listening to it and thinking it’s interesting to hear it stripped down like that, and I went, “You know, I could do something like this. This is kind of soulful, has a beat to it.”

Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone is a phrase from your father’s poetry, and with “Compassion” you put one of his poems to music for the first time. Why did you choose to do that now? It’s something that I’ve been wanting to do for along time, actually. I’ve been sort of playing around with this other poem of his called “Why Does God Permit Evil.” It’s one of his earlier poems. It’s much longer, though, so it proved to be pretty challenging. I knew I wanted to call the album Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone, and the next logical step would be try to take the poem and make it into a song. I guess part of it was the pressure of trying to do it in time. In part it’s a tribute to my dad. He has Alzheimer’s and he isn’t able to write anymore.

I’m sure you played him the song. Yeah, I played at a music festival recently, and he wasn’t able to go to the festival, but I put on a little house concert at the house with some close friends and just me and my guitar, and I played it for him. He was thrilled. He has a pretty good sense of humor about things. I mean he knows he has Alzheimer’s, and who everybody is and all. He’s just physically a little feebler, so that’s why he wasn’t able to go to the concert. As far as him not being able to write, it’s just like a focusing thing as a result of the Alzheimer’s. It’s a horrible, dreadful disease. I hope they find a cure for it soon.

My grandmother has dementia, and it’s just such a complicated thing to deal with. It is. And everybody’s on different levels of it and some people go faster and sooner than others. You just never know. Like when I leave there after I was visiting. I don’t know what I’m doing to find when I come back.

You’re the type of artist for whom the word “veteran” is easily tacked onto your name: “the veteran singer/songwriter.” What do you think about that? I’m a certain age, but I don’t know what that age is supposed to feel like. I’m a much younger 61 than most 61-year-olds. I have to remind myself sometimes that I’m 61. I know I’m somewhat of an anomaly, where I am creatively and all, because a lot of artists of this type of art—not necessarily jazz and blues, but you know, rock/pop world—most artists create their best work early on and they just kind of fizzle out, and I seem to be doing the opposite. Sometimes I look at that, “the legendary queen of Americana,” and I go, “Wow!” You know, It’s flattering I guess, but I don’t really think about it until I see it written down.

When you listen to your records from when you were younger, what do you hear? I don’t compare it to now because it was so long ago and I just look at it for what it was at that time. I mean, I like what I’m doing now better, but that’s how it should be. At the same time I realize how important the Rough Trade album was for everybody and how special it was. They all have their places in my musical history and everything.

What’s the feeling, during a live show, of playing a song that you made when you were 25 years old? Some of the songs hold up better than others. In almost all my shows I play “Change the Locks” from the Rough Trade album and I always play “Drunken Angel” and “Lake Charles” and “The Night’s Too Long.” I like doing those songs. I think they held up. If they hadn’t held up I wouldn’t do them. I enjoy pulling out some of those other songs because they have such a history behind them. It’s kind of funny for me to think that I have songs that are kind of like my little hit songs. Like “Drunken Angel” is kind of like, everybody just wants to hear that song all the time. Sometimes I’m like, “God, do we have to play this song again tonight?” but I still love it and everything and I have to acknowledge that for the fans. I can’t go out there and play all new songs. The more songs I have, the more challenging it becomes putting the set list together.

Are there parts of being a working musician that feel new to you now? Recently we were in Nashville and I went over to CMT studios, which I thought was amazing—I never thought I’d live to see the day where I’d be doing something over at CMT. But they now have this Americana division and the people who are doing that are huge fans of my music, so I met with them. They did this thing where they invite the artist to come in and record them singing like four or five songs. Just a couple cameras. And then they put it online with their thing that they do or whatever. So I did that. I’m trying to cooperate with all that kind of stuff. I don’t really enjoy doing a lot of that extra stuff that I have to do, but I’m just glad that it seems like what I’m doing is now finally—the styles seem to be all kind of running together, especially in Nashville and everything. Like Country Music Television recognizing the Americana style and making room for it and acknowledging it. It used to be way on the outside and I’m noticing that one world is starting to seep into the other one.

In a similar vein, you had a song on Nashville, right? One of my songs was featured in it. They recorded it, not my recording. Called “Bitter Memories.”

Do you have any thoughts about how Nashville as an idea is something that can be sold? To be honest, I still haven’t seen the show yet. But the way I got involved in it was through T Bone Burnett and Buddy Miller. T Bone—he’s a very good writer, he was the music director and then he left and now Buddy Miller is. So they pulled me in as a songwriter. Whenever something more commercial like that acknowledges me as a songwriter and wants to use one of my songs, I just go, “Yay, awesome.” I see it as a positive thing. What I’ve started to see is that some of the people who work in that genre of the more commercial world are also fans of my music. That’s what I’m starting to see, that crossover thing of the commercial world versus my world. Also, just as an aside, I love Connie Britton. I loved her in Friday Night Lights.