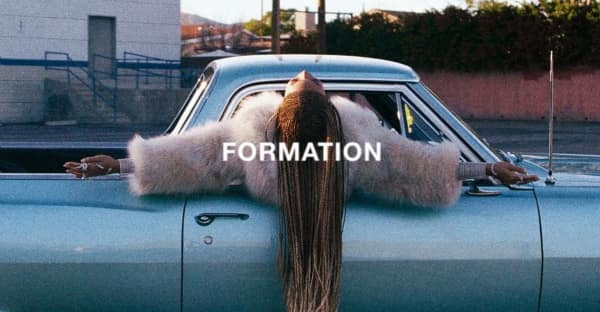

Rarely does one song so culturally specific in its intent evoke such force. On Saturday, Beyoncé released "Formation"—her first release since 2014's lush "7/11"—on Tidal, along with soul-stirring visuals on YouTube. The song and video position the Houston-born pop star's politics front and center: What is happening to America's black citizenry, specifically its black women and black queer communities, will no longer be tolerated. This is our story to tell, this is our history to revel in, this is our revolution to lead, the song says. "Formation" is meant to provoke and prod the masses; it is meant to be uncomfortable for outsiders looking in. It is meant, simply, to be a statement.

Writers Judnick Mayard and Doreen St. Felix join FADER editor-in-chief Naomi Zeichner and FADER Canada editor Anupa Mistry for a discussion about black women narratives, visibility, responsible pop music in 2016, and Beyonce's "kitchen politics."

Naomi Zeichner: For me, “Formation” is a song about how greatness arises from being of people, and with people. Among this song’s promises is that people can work together, instead of alone, to reflect their best selves. If Beyoncé came to slay, she brought her dancers to slay, too. The message reminds me of Barack Obama’s 2016 State of the Union address, which basically begged Americans to learn about the future and then work together during this time of extraordinary change.

Beyoncé has long made explicit her appreciation of sisterhood—whether by living with adopted sister Kelly Rowland during the peak of Destiny’s Child, talking about the importance of a female support network ahead of becoming a mother in her 2013 HBO doc, or projecting that FEMINISM banner on her 2014 VMA performance. But the group Beyoncé evokes in “Formation” feels more significant—with this song and video she is placing old South and new South together “on a continuum,” recognizing everyone who has had "this face and this hair", and thanking Houston, Texas for feeding her. As she applauds her own ability to dream it and then own it, she seems to be acknowledging that those victories are to the credit of not only herself but her parents, and her daughter, and all of the people who have nourished her. And if she wins with them, in “Formation” she also drowns when they drown, or is regenerated as they are baptized.

“Formation” ends with the line Best revenge is your paper, which is how I think Swae Lee—the 20-year-old half of Rae Sremmurd who co-wrote the song—will eventually avenge Ebro Darden, the Hot 97 and Beats 1 host who diminished Lee's contribution on Saturday, seemingly missing the song's point that good shit happens when people achieve and seek knowledge together. I’d argue that protecting and honoring the people around you, and having them do the same, like "Formation" suggests, is another form of revenge. Still, not everyone is Beyoncé, and she delivers that revenge line deservingly and exhilaratingly: like a woman who just shook up her whole team, whose rollout plan will set trends that magazines like this one will follow for years, and who will be remembered as the black Bill Gates in her family, over her husband or father.

Doreen St. Felix: I want to talk further about cultural specificity. "Formation" is Beyoncé's "The South Got Something to Say" Moment. This time, it's femme, queer, and luxe. It's wet. This time, Messy Mya is the prelude, Big Freedia the interlude, and no straight black men are to speak. Regional culture sometimes gets squashed in national narratives about blackness in the general public, since that term connotes a universality the global black experience obviously negates. Formation is precise, it's familial. Beyoncé is named after her mother's bloodline; Celestine's maiden name is Beyince. The matriarchal line coursing through her veins has been as consistent a fact as possible, in her career and also in her life. Her generational Southerness has come out in her discography much more furtively, every sixth single or so, whenever her voice enters a lower register. (King Beyonce is her most masc when she's invoking H-Town). "Formation" is an explication of her Louisiana and Alabama heritage so elemental it literally gets down to the level of food—"hot sauce in my bag," etc.

Cultural specificity, I think, also explains what's being misread as unfettered capitalism in the video itself. Black materialism, black luxe, is not radical. But the culture of self-luxuriating and self-adornment the visuals display—whether that be buying wigs for a regular-ass girl, or rocking Givenchy if you're Beyoncé—is distinctly Southern and can be accessed across all classes. We like to look good, and we always will, no matter how much they take from us, no matter how hard they try to drown us.

“To believe that Beyoncé is so rich and loved that she doesn’t experience racism, that she doesn’t feel traumatized by the images of murdered black bodies is to erase her.” —Judnick Mayard

Judnick Mayard: When Beyoncé drops something the conversation often swings left into some sort of argument for men. With the last project, everyone claimed Jay had guided her to into this confidence and sound, which is simply foolish. The real glory: we are watching a real flesh-and-blood black woman grow through several stages of her life before us.

Beyoncé, too, has been traumatized by the events of the past decade in this country, specifically the past three years which have poured gasoline on a movement that seeks to literally protect black bodies by affirming blackness. Not conforming, not assimilating, but getting into formation and demanding information about who we are and what we seek.

That Beyoncé leads this charge is absolutely not surprising at all. She is the blackest pop icon since Michael Jackson. She married her black rapper husband who used to sell drugs in Brooklyn but now represents players running corporations and carries her beautiful black daughter—whose hair is not styled to assuage the media or the public, black or white—without a bother. She’s in the perfect space to speak to economic justice and to otherness. Beyoncé is always toted out as the Mother Teresa of blackness. She's palatable for white moms across the country who want to feel "sassy" and "fierce" and dance with their daughter. She's light and polite for those who want to sell you respectability as the only way to overcome, but Bey is nobody's fool.

To believe that Beyoncé is so rich and loved that she doesn’t experience racism, that she doesn't feel traumatized by the images of murdered black bodies is to erase her. They want you to forget that her blackness is rooted in a real “Texas bama” history because she's not projecting a monolithic idea of blackness. But this is Beyoncé, and this is what she cares about. She came to speak to us because, like every other black person living in this time, she knows we need unconditional and honest love.

Anupa Mistry: Ah yes, Nikki, I am so glad you go there. What's been most fascinating for me to watch is how much "Formation" and Beyoncé's political assertions are truly outing the fools amongst us. And I'm not just talking about the obvious naysayers, the Republicans or the pro-police militia trolling for RTs; there are so many dudes who find something fearsome in Bey's agency. As skeptical as I can sometimes be, I did not watch "Formation" and think of the sophistry that it might take to write a song and create a visual piece that is so densely situated in Bey's uniquely black-American identity. And yet, all over Facebook and Twitter there were men talking about the impossibility of a black woman pop star as complex. It is deeply maddening.

I'm not sure how a weave or choreography or fiercely protecting your commodified body—the image of which makes you, but also others, very rich—makes a woman any less 'militant.' Or why militance, which feels outmoded as we are further suffocated by capitalism, is something to aspire to. But I am very confident that the ideas both Nikki and Doreen put forth here make a case for Beyoncé as what art, particularly art that is explicitly created for-profit and for maximum consumption, should aspire to in a time of growing consciousness and power for marginalized demographics across America and all Western nations. "Formation" feels empathetic, affirming, responsive and present. Video footage controversy aside, I'd venture that it's pop at it's most responsible in 2016. Watching "Formation" gave me a feeling similar to when M.I.A. put out "Borders" and the xenophobic violence in the wake of Paris felt like a nightmare. I am grateful for these women who can't step out of their black and brown skin, no matter how much money they have or what zip code they live in, using their power to validate the rage and activism of people and their young fans.

And, you know, as we suffer through so much debate around rap lyrics and the n-word and how to negotiate that amongst friends, colleagues and in public spaces, I love the idea of Beyoncé putting her white, and non-black, fans in the position of absorbing and reciting a message that is deeply for black woman.

“’Formation’ is Beyoncé’s ‘The South Got Something to Say’ Moment. This time, it’s femme, queer, and luxe. It’s wet. This time, Messy Mya is the prelude, Big Freedia the interlude, and no straight black men are to speak.” —Doreen St. Felix

Naomi: Do you all think it’s important to preserve some space for Beyoncé naysayers, in the way it’s important to preserve some skepticism with anyone this powerful, or anyone who controls their own narrative this tightly?

Is it good that Beyoncé, whose politics are so vital in this moment, never tweets and rarely gives interviews? Would talking more mean that the impact of something like this video would be watered down, or somehow less exhilarating and chilling? We knew Beyoncé was following Deray on Twitter, and we know Solange Knowles is often a voice of reason in conversations about police brutality, but this still felt like a public coming out party. I don’t think it makes Beyoncé any less militant to carefully curate the way in which she choreographs how she delivers a message, but I also wonder—will it ever be easier for her to speak in public more often?

Anupa: When I think about the control Beyoncé wields over her image, privacy is obviously at play but the word that most often comes to my mind is protectionism. That goes two ways; protecting herself as a corporate entity/industry, but also protecting herself as a woman, and a black woman, in America. I'm all for hearing out the skeptics who can offer a counter-analysis of Beyoncé and her influence that acknowledges there are multiple ways to be a woman, to be black, to be American, to be a capitalist.

Still, I can acknowledge that I'm sensitive about her in a way that I don't extend to a lot of artists: so when bell hooks says things like "Beyoncé is a terrorist" it bugs me out. I know that her aesthetic—blond hair, small waist, light skin—are in collusion with a pervasive, sometimes destructive beauty standard. But isn't that what makes Beyoncé's obvious interest in presenting bigger truths, her willingness to say "stop shooting us," to present what Nikki calls "the normalcy of black women," to shrug off more and more of the white gaze and suffuse her work with that code Doreen refers to, even more powerful? And when I say that, I'm not suggesting that attractive, wealthy people who are woke are better than the rest of us, but that despite being rewarded for her incredible talent and for fitting into the narrow confines of her industry, she remains a woman of—I believe—moral integrity.

Doreen: The 16 year old who did "Bills, Bills, Bills" is the 34 year old who put out "Formation." A good artist will have a politics, but artists are not politicians. Beyonce's is a "kitchen politics" which happens to center itself on those woman-ish issues that aren't "buzzy," like police brutality, and she's always been that way. The desire for black artists to speak out in plainly accessible terms about the so-called issues of the moment undermines the role of the artist. It also underestimates, in this case, the way information traffics in black femme spaces, which is often in code, in visuals, often uninterested in centering white or even male interpretation. I don't see why Beyoncé should forfeit her aesthetic for 140 characters; she owes nothing.

I'm more than willing, in fact, and deeply interested in listening to Beyoncé skeptics put forth their critiques. What I'm not interested in? Naysayers whose screeds drip with blatant misogynoir, or general misinformation about what it means to be a black woman in America. And that's the bulk of it. The hierarchy of identity in this country means no one but black women knows what it’s like to be a black woman. That's why the affirmations we make of ourselves get misconstrued as a threat to white people or to black men.

Judnick: Beyoncé is speaking to the every day of our lives, our trauma, our truths. Beyoncé is presenting our normalcy. That’s why the first line is so powerful: You haters corny with that Illuminati mess. She's not just dispelling the idea that some black shadow of magic is responsible for her life. Even better is the insult. Corny people are disingenuous fools. They are not to be taken seriously and, worse, would rather usurp than create. Beyoncé seeks to create, which means, no, she can't really leave space for the naysayers—because to do this she has to not give a fuck. She has to believe what she knows is true, because she's lived it. This is important in giving black women visibility, in giving them ownership of this image puts forward, and in highlighting the solidarity of her power, presence and work. She went from hiding her daughter’s face to presenting her proudly as a beautiful free Afro’d black child. Never mind her dancers, Beyoncé employs women of color in her band, in her team, in her work. She "rears" her man, but she employs her sisters. The magic to us is that we can finally see ourselves in this way, too.

Black music, too, regularly features the story of a Black Madonna, a figure who works to protect and nurture her young through overwhelming adversity. It's a reality for many—not just a spirit animal, as some claim Beyoncé to be.