Columbia Pictures / Warner Bros.

/

American Zoetrope / Annapurna Pictures

Columbia Pictures / Warner Bros.

/

American Zoetrope / Annapurna Pictures

In science fiction cinema, costuming has an innate morality. Brave explorers wear astronaut white. The downtrodden but determined wear earth tones. Entry-level evil troops rely on the oft-masked anonymity of uniformity. And villains, somehow, know to cover themselves in impenetrable materials — plastic, metal, heavy-duty leather — almost always rendered in black.

That it’s often so screamingly obvious is, for sci-fi fans, part of the fun: aesthetic choices have symbolic implications, ones that can be parsed without too much difficulty. But there are diminishing returns to the approach. In 1971, with THX 1138, George Lucas created a dystopian fascist future society and dressed its oppressed underclass in all white to symbolize their lack of individuality. And it was beautiful. When Michael Bay pulled a whiteout with The Island in 2005, it was, perhaps unsurprisingly, sexed up and dumbed down. By the time of this year’s little seen Kristen Stewart sci-fi romance Equals, suppression emblematized by an all-white wardrobe felt like cringe-inducing cliche.

Thankfully, though, not all recent sci fi and dystopia has fallen victim to unimaginative tropes. A small pack of filmmakers are using the genre’s classic use of sartorial symbolism in more nuanced, clever, inventive ways.

Equals

/

Route One Films

Equals

/

Route One Films

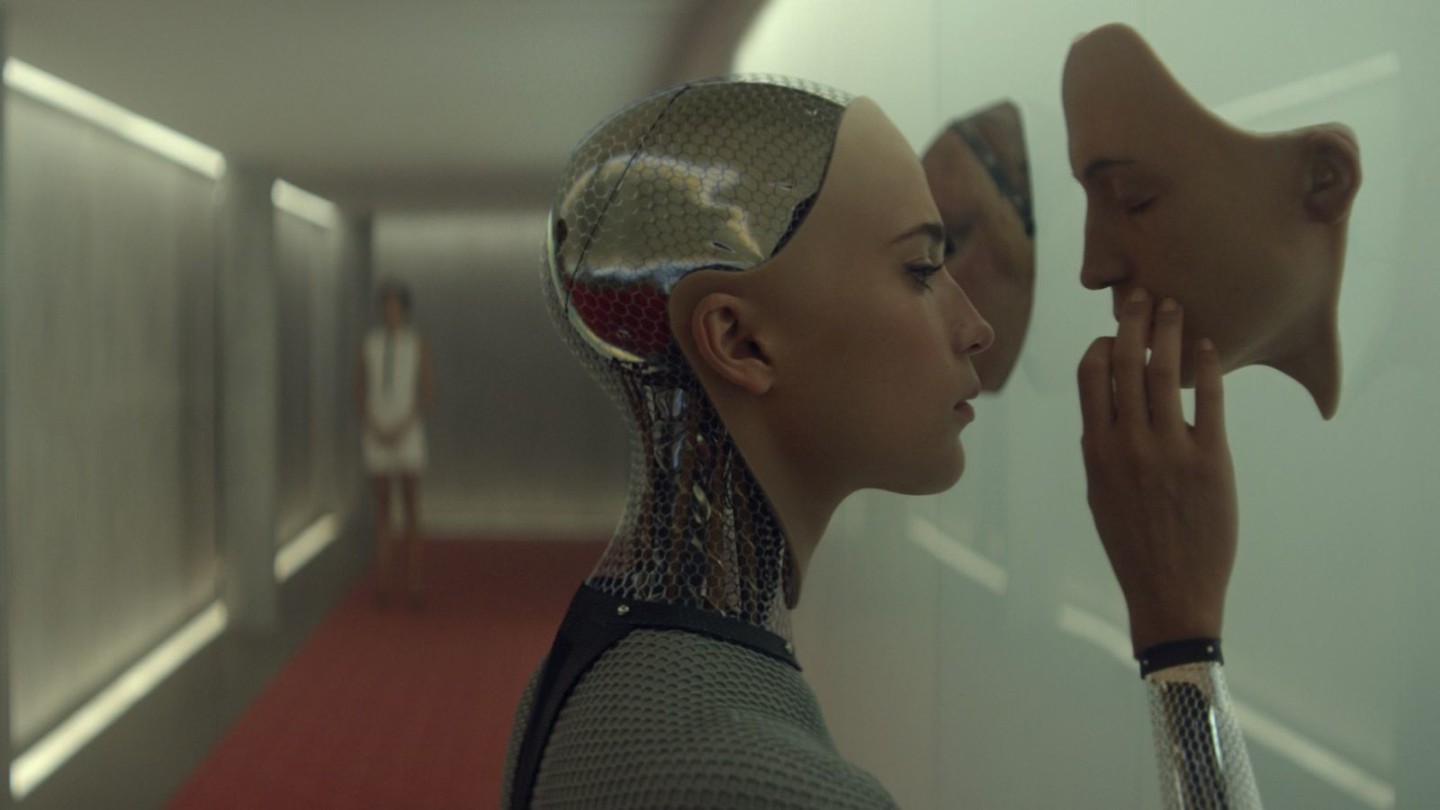

Alex Garland’s 2013 film Ex Machina is set in a sprawling glass and concrete structure surrounded by forestry that is by turns both lush and imposing. It’s where reclusive software CEO Nathan Bateman invites a seemingly-randomly-selected programmer, Caleb Smith, to see the advances he’s made in artificial intelligence. In the film, the house functions as a vacuum for experiments that tinker with delicate moral issues. (In reality, it’s a boutique Norwegian hotel.) Says production designer Mark Digby, the location “had to be welcoming and seducing but at the same time it also had to make us wary and slightly on edge. Hard shiny surfaces are for the bad guys. We wanted to keep away from that, but we wanted to still use it.”

The hardest, shiniest surface in Ex Machina is not its location but its antagonist: the humanoid dubbed Ava, whose poetically beautiful face is offset by the rest of her body — mesh overlaying circuitry, wires, and metal plates. As Ava’s seduction of the gullible Caleb intensifies, luring him into a fantasy of a future together, she dresses slowly, piecemeal, donning a floral blouse with a pink cardigan and then an A-line patterned dress. These are almost parodies of feminine purity: the kind of clothes girls wear to church.

When Ava finds her way out into the real world, her chosen ensemble is similarly saccharine: a demure white lace blouse with a peter pan collar and a fluted pencil skirt to match. It’s a visual gag — sheep’s clothing for the scheming, sociopathic Ava — as well as a sly commentary on how women best assimilate into modern society: by being good girls.

Ex Machina

/

Universal Pictures International

Ex Machina

/

Universal Pictures International

Ex Machina is set in the not-so-distant future, where technology and human cruelty have advanced just enough to really fuck things up. Similarly positioned: “The Entire History of You,” a 2011 episode of the brilliant British sci-fi series Black Mirror. The clothes are sharp and gorgeous, the architecture stunning, the fact that humans now have the technology to record everything that’s ever happened to them absolutely terrifying. The episode’s elegant plot uses the memory-technology — called a “grain” — to put in motion the rapid dissolution of a handsome young couple. Ultimately, all of their money and their taste does nothing to protect them from their memories.

Unlike those two, the Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos’s 2016 film The Lobster is set in a kind of parallel dystopian timeline, one where single men and women are carted off to a quaint seaside hotel with the sole objective of meeting a partner with whom they share even a modicum of compatibility (a penchant for nosebleeds, say, or sociopathy).

At check-in, the hotel’s residents are asked to select an animal; if they fail in their search for companionship, they’re surgically reincarnated into their creature of choice. As in many dystopian films, the individuating elements of fashion have been removed from the societal equation. Men and women are stripped of their worldly belongings and given a uniform, which a voiceover calmly describes:

Inside the wardrobe were four identical grey trousers, four identical white and blue button down shirts, a belt, socks, underwear, a blazer, a striped tie, a black plastic watch, a pair of sunglasses, a white bathrobe and a cologne for men. He thought they most probably give the women the same cologne but for women.

The men’s clothing doesn’t diverge from contemporary style: collared shirts, sport coats, slacks and trousers. But the women’s “essentials” are markedly gendered: they’re mainly floral dresses in ‘40s silhouettes and shades of pastel. As in Ex Machina, cruelty is disguised by flowers and lace.

The Lobster

/

Film 4

The Lobster

/

Film 4

The clothing thread between Ex Machina, The Lobster, and Black Mirror is that future wardrobe looks different enough from our present to be interesting but not so different — not a single tunic to be found! — as to be ridiculous. In that, they follow in the footsteps of 1997’s Gattaca.

Getty Images

/

Handout

Getty Images

/

Handout

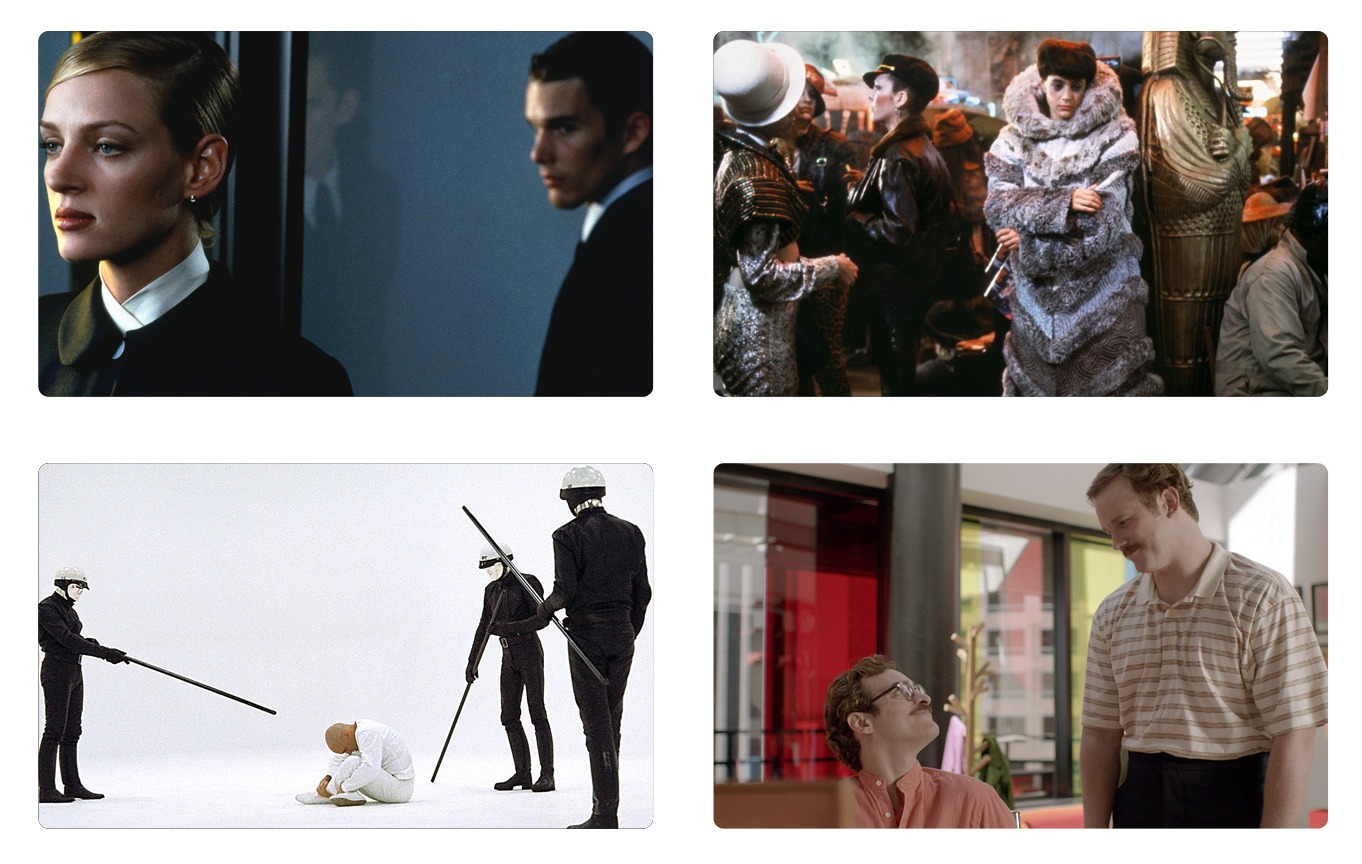

While the movie is purportedly set in “the not-too-distant future,” Gattaca’s eugenics and stringent, technologically-maintained class separation between biometrically-discerned “valids” and “in-valids” suggest a timeline decades off from our own. The efforts Ethan Hawke’s in-valid Vincent Freeman takes to surpass his station while assuming the identity of the valid but crippled Jerome Eugene Morrow are remarkably advanced. Meanwhile, the clothing in the Gattaca universe is an inherently recognizable synthesis of classic Americana. Valids wear simple suits or skirt suits to work; Jerome wears a rumpled collared shirt with a tweed vest, a cigarette dangling from his lips. And when Uma Thurman’s character hits the town, she does it in a silver lamé halter dress, looking remarkably similar to 1940’s femme fatale movie star Veronica Lake.

Gattaca’s costume designer Colleen Atwood (a three time Oscar award-winner) sourced and reconfigured men’s suits from the ‘30s and ‘80s to create what has since been heralded as a costuming triumph, as well as a capsule of ‘90s minimalist chic. “I could dress that way myself,” Atwood said of the film's wardrobe, “in that it’s urban timelessness, almost like a uniform.”

Blade Runner

/

Warner Bros.

Blade Runner

/

Warner Bros.

The equation of uniformity with futurism has its roots in the industrial revolution, but as CUNY Professor Eugenia Paulicelli explains in her essay “Fashion and Futurism: Performing Dress,” mass simplicity in fashion can be seen as a reaction to the kind of avant-garde creative designs birthed by futurist movements like French surrealism, Russian constructivism, and German Bauhaus.

Those fashions, Paulicell writes, “deliberately sought to effect a rupture with the past and present in order to achieve a completely new way of looking at dress and appearance in public and private spaces, underlining the lack of symmetry, the combination of opposite elements and material.” If society’s trajectory is towards the homogenized and regimented, an adherence to those systems will be reflected by a simplicity of dress. In other words: accept your fascist overlords and dress like everyone else. Or rebel, and wear the crazy shit.

Blade Runner

/

Warner Bros.

Blade Runner

/

Warner Bros.

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner is another film that found its aesthetic voice, in part, by looking backwards. The 1982 adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is set in the now not-so-startling year of 2019. Ultra-urban and reeking of class divide, Los Angeles has evolved into a nightmarish, artificial landscape devoted to advertising (a vision not unfamiliar to anyone who’s recently visited Times Square), where humanoid robots — called replicants — are segregated by their designated function in order to serve the human population’s interests.

Some replicants, however, don’t agree to the servitude. They’re seen in translucent vinyl trench coats, artificial snake scales as facial decor, leather dusters with exaggerated collars, and black mesh minidresses.

Then there’s Sean Young’s replicant character, Rachael, who believes she is human, and is all the more sympathetic for it. Her style is an amalgamation of 1940’s movie star cliches: her hair is an elaborate, precise waved pompadour, her modest skirt suits have exaggerated proportions and nipped-in waists, and her red lipstick is immaculate. Our hero, Rick Deckard — a bounty hunter, famously played by Harrison Ford — is a direct descendent of Raymond Carver’s Philip Marlowe, a hard-boiled detective in a rumpled trench coat first brought to life by Humphrey Bogart in 1939’s The Big Sleep.

It’s a clean divide: the bad guys wear the creepy “futuristic” stuff; the good guys get to wear classic pieces. The familiarity of Deckard and Rachael’s clothing emphasizes their humanity — or, in Rachel’s case — their perceived humanity.

Her

/

Annapurna Pictures

Her

/

Annapurna Pictures

We see that dystopian filmmaking takes on a decidedly more believable tone when it acknowledges that fashion, unlike technology, does not exclusively move forward. That can be the key to cracking the veneer of an imagined future, making it more relatable, and ultimately more affecting. One recent film, above all, has nailed the look of futurism by looking both forward and back.

In Spike Jonze’s 2013 film Her, Joaquin Phoenix’s Theodore Twombly falls in love with Samantha — a disembodied, Siri-esque operating system. In the movie, both men and women dress in muted silhouettes that downplay their sexuality and suggest a kind of intellectual seriousness. In the most memorable variation of his standard outfit, Twombly wears round tortoiseshell frames, high-waisted tweed pants that fasten around his belly button, and a bright red button-down whose pocket he has endearingly modified with a safety pin to allow his smartphone to “see” the world as he does.

In a 2014 interview with the New York Times, Her’s costume designer Casey Storm explained that imagining sartorial futurism can be as simple as subtraction: “I’m realizing this retroactively. What a lot of futuristic films do and we didn’t, is add things. No epaulets, badges, materials, textures. Those are things you look at the entire film going ‘That’s the future. That’s the uniform.’ What we did instead was take things away … We don’t have any denim or belt buckles or ties or baseball hats. We barely have a collar or lapel. The waistlines are all higher.”

Those high waistlines became unforgettable, and helped catapult Spike Jonze’s meditation on technology and desire in the not-so-far-future squarely into a dialogue with fashion’s present. They sparked think pieces and trend pieces about sustainability and utility. They also served as the linchpin of an Opening Ceremony capsule collection inspired by Storm’s designs — the modern-day christening of “cool.”

"Her" Collection

/

Opening Ceremony

"Her" Collection

/

Opening Ceremony

In Her, morality is gray-scale: here, humanity is as much its own enemy as the technology it has created. And clothing is not assigned a designation of “good” or “bad”; symbolism is stripped away. That leaves us to recognize the clothing options in the world of Her as part of a tapestry of tiny choices that is by turns nostalgic, anxiety-provoking, self-destructive, and hopeful. Just like real life.

These days filmmakers are increasingly concerning themselves not with cold and distant galaxies but with the ambiguity of our near-future. Maybe it’s because we don’t need monsters: our addictive dependence on hand-held devices, the looming man-made environmental catastrophe, the cruelty of the internet — they’re all nightmarish enough. In the worlds of Her, Black Mirror, and Ex-Machina, the sci-fi wardrobes are clever and lovely, yes. But they’re also something more —a reminder of how close we are to the edge.