Dion is a construction worker and cherishes his weekends dearly. One August afternoon, in the back of his house in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, he’s got a sort of cabana set up. Underneath its canvas roof, cushions cover wicker furniture. Someone has tossed a set of foam nunchucks on the ground. Dion’s cousin Kaseem “Ka” Ryan, a 44-year-old rapper who was raised in this house, picks up the toy weapon and starts swinging it idly. There’s a speaker playing adult contemporary radio oldies. Occasionally, everyone sings along.

In the 1970s, when Ka’s grandparents owned this place, it was the only house on the block. Surrounded by vacant lots, you could see straight through to the avenue three blocks over. But the house was crowded in its own way, packed to the gills with more than a dozen aunts, uncles, significant others, and kids. Growing up, Ka, whose stage name is the nickname his mama gave him, sometimes resented it. “As a kid, I always thought, Why the fuck we here? Why did my family have to be here in this place?”

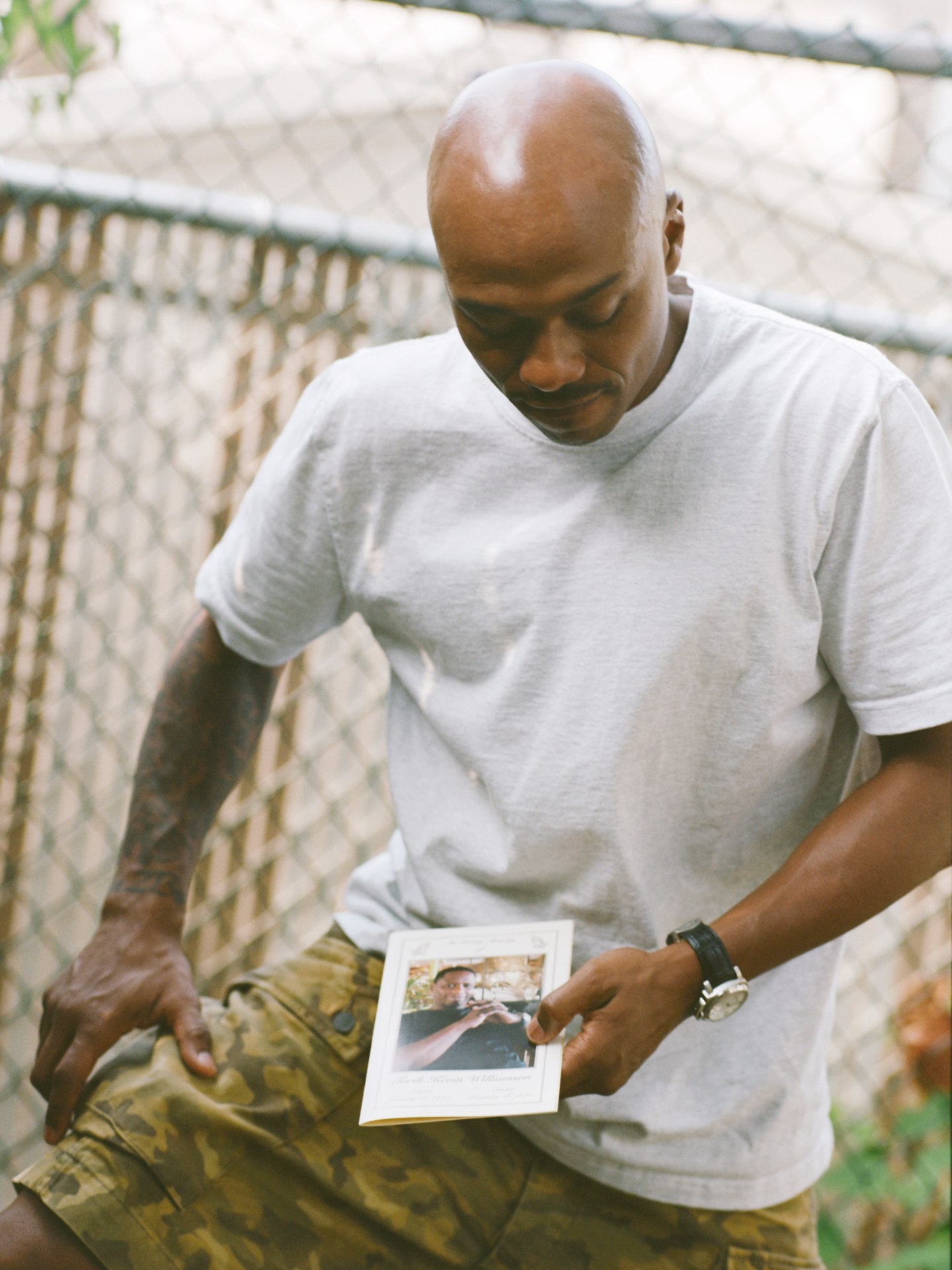

Now the home is owned by three of the cousins he grew up with: Dion and LaVaughn still live there; Mikey is currently incarcerated. The block has changed, too, and today it’s charmingly residential and middle class, with stainless steel gates fencing in well-watered lawns. Ka and Dion have the air of concerned parents as they sit down to chat and check up on the welfare of their younger kin. Ka phones his baby cousin Shania, whose father just got out of a rehab halfway house, to make sure that the $300 he sent for school supplies has arrived through Western Union. “The part I like about having something now is being able to help,” he says.

LaVaughn, who goes by La, comes by to meet Ka and Dion. He wears a polo and a Yankees fitted, and when he smiles, which is often, his silver teeth glint in the sunlight. He is impressed with how far his cousin has come. “He nasty, you know, like a philosopher!” La says. “When we was 8 or 9 years old we was recording. We was in the basement one day, we put it on and we went at it!” Suddenly, time is fluid, slipping backward, and the cousins start speaking a different language. There’s talk of a time before microphones. Gangsters being “trucked,” or decked with an unwieldy amount of jewels, like Slick Rick. Early model Motorola phones the size your head. La asks Ka if he recalls what predated rims. “Remember when we was riding with the chrome spokes?” Ka claps him on the back. “We old niggas, b!” Ka says. “For real.”

In 1989, Dion gave Ka a thousand dollars to jumpstart his music career. “Dion gave me the nicest gift I ever got, to this day,” Ka says. “It started me in a real studio. I loved him from before that but I loved him forever after that. A thousand dollars was a million dollars back then,” Ka says. Dion reminds Ka that the support was mutual: the two used to sit on the stoop and talk through their problems, late into the night.

In the early ’90s, Ka made a name for himself around New York with a group, Natural Elements, and later as half of the duo Nightbreed. Both acts, unsigned at the time, generated some buzz with their old-school rap battles, but neither found mainstream success, and as the years marched on and multi-syllable rhymes and pared-down production grew less popular, Ka says he became tired of trying to fit in. “It got to the point that it wasn’t as respected as it used to be,” he says of his style of rhyming, which prizes ruthless lyricism above all.

In 1999, he quit focusing on music and became a firefighter. He worked his way up the ranks of the fire department for a decade until, just before making captain in 2009, he realized he was missing what had been a huge part of his life. “I think of rhymes everyday, I can’t not,” he says. “I can’t help it. It became hard to stay away.” And so Ka got back into it, with greater success than ever. Across the solo albums he’s released since his 35th birthday, he’s amassed a cult following, and found a sense of personal peace. “I feel like I’m finally becoming self-actualized,” he says. “No one knows what they were put here for but what I do best is write rhymes, that is my gift for this world.”

A week before Ka and I meet, he is featured on the cover of the New York Post, in a story headlined “FLAME THROWER: FDNY captain moonlights as anti-cop rapper.” The hit-piece was surprising as much for its strange argument about Ka’s “bad-mouthing” police — which was based on a few lines from songs that were four years old, then paired with some disparaging quotes from the leader of a police union — as it was for its unlikely target: an independent rapper with a job serving his community. “Ka should be celebrated as a New York treasure,” the rapper El-P wrote in a supportive tweet, adding, “Before writing a hit piece it’s good to ask yourself: ‘Has the man I’m trying to destroy saved more lives than me?’”

In the backyard in August, and across a series of follow-up interviews, Ka is adamant in his refusal to comment about the hit piece. “With love comes hate...can't have one without the other,” he tweeted himself the day the story came out. Whenever I bring it up, he evades the question and my gaze. “Some bullshit in the papers,” his cousin says, and they get right back to chopping it up.

Ka has moved around New York — he currently lives in Windsor Terrace — but Brownsville is his home. “Every block I’ve lived on wasn’t my block,” he says. “Hull Street was my block. I caught the ringworms on that block. I played in the lots on that block. I fought on that block.”

Looking back on his childhood, he remembers playing with friends on stinking mattresses left in the streets, and how sometimes his home phone would cut out, when crack addicts shimmied up nearby phone poles to cut the line and salvage its copper. The toxic smell of smoke would suffocate the area. If not for Fresh Air Fund, I’d have died in the smog, Ka raps on 2016 track “That Cold and Lonely,” referencing a non-profit that pays for vacations in the country for low-income inner city youth.

His father was locked up until Ka was “maybe 6 years old,” he says, but after that, both of his parents were around, trying to keep life calm as possible for him and his little sister. At the grocery store, they were regulars in the “no frills” aisle, and Ka remembers his mother coming home with bags of brown rice that they would pour out onto a table and remove pebbles from. They supplemented discount groceries with government cheese and powdered milk. Their caretaking extended to many of the neighborhood kids too. “When he came home, my pops was like the pops of all my friends,” Ka says. “It was a big responsibility, man. It ain’t too many fathers in the hood. Especially in the ’70s and ’80s.”

“In the ’70s, the community raised you,” Ka continues. “You step out in the street and [your neighbor] would tell your mother.” Things changed with the arrival of crack cocaine. “It became less community and more just me like, ‘Yo, I’m getting money, fuck everybody else!’ It was because certain people were acquiring money. Somebody’s going to sell these drugs, it might as well be me. It messed up the growth of the community.”

The late ’70s was when Ka first started rapping, after his older cousin La got out from the now-shuttered Spofford juvenile facility in Hunts Point. La rhymed, and before little Ka followed in his footsteps, he provided percussion. He would bang on cars for beats — the same cars that they sometimes jumped up onto in order to evade the neighborhood’s packs of wild, rabies-ridden dogs. “Before we ran the street, the dogs ran the street!” Ka says, dissolving into laughter. “But real talk, I was on fire after that.”

The cousins were coming into their own as emcees during a storied era for New York rap, and La proudly runs down the genealogy of Brooklyn legends he and Ka are supposedly connected to. Their cousin Lil Pop from the barbershop, immortalized in a shoutout on Biggie’s “Warning.” Busta Rhymes, who La says he used to beat up in grade school. Spliff Star, who they used to play dice with. Nas, who La drove around while working for a limo company (he was a bad tipper). And Jay Z, who La claims to have once almost robbed on the corner of Marcus Garvey and Willoughby in Bed-Stuy. The story is almost too much to believe, which could just mean it’s true: “This was like in ‘84. Jay was on the corner rapping. I was like 14. We listening to him rhyme, me and my stickup crew. We was watching him, but he ain’t have nothing on. I got tired of it so we left.” La tells me I can put it all in my article, and grins wide.

La grew up around the same desperation as Ka. “The struggle is why we rap,” La says. “When you struggling so much, you want to tell someone. It’s like venting. You don’t have nobody close sometimes to listen, so why not?” Today that struggle is different, and the city often has a different face. Reminiscing, Ka can’t believe that people new to Brooklyn are unaware of just how poor and violence-scarred neighborhoods like Brownsville and Bed-Stuy were just a couple of decades ago. “Where you going right now to get your coffee from was crazy, yo! People don’t understand that. I had to be on point every block I went on. People was hitting you with a buck fifty on your face, just for nothing,” he says, referring to a slashing requiring a great number of stitches.

Ka left Brownsville in his twenties, moving to Bed-Stuy and bouncing around a couple of spots there. From 1990 to 1998, he attended school at The City College of New York, in Harlem, taking just one class per semester while trying to focus on sparking a rap career. “I didn’t do well in school because when the teachers was talking, rhymes was coming into my head and I couldn’t fucking focus,” he says. “I just wanted to be dope, and I wanted to rhyme.”

His first steps towards a professional rap career were as part of Natural Elements. Brought together in 1993 by the Bronx-based producer Charlemagne and signed to his label, Fortress, the crew was comprised of L-Swift (now Swigga), Mr. Voodoo, and Ka — others joined and eventually left the group, including G-Blass, Howie Smalls, and the InTimidator. They started getting some traction after doing freestyle sessions on the legendary radio show Stretch and Bobbito — it was actually in that same studio where Ka first met Mimi Valdes, who is now his wife, escorting guests up to the booth. After the radio show stints, record labels took interest in the crew. Def Jam invited them up to their offices, and there was talk of a deal. It never materialized.

Ka blamed himself. “I wrote a lot, but stylistically, I didn’t have it,” he says. “I wanted to be better, [but] I was the weak one in the group.” He quit Natural Elements, and soon after the group was signed to Tommy Boy. “That’s how wack I was: as soon as I left they got a record deal,” Ka says. While Natural Elements worked on their debut album, which was first delayed then ultimately never released, Ka moved on to form a new group, Nightbreed, with his childhood best friend Kev, who died tragically in a car accident in 2015.

By 1999, however, unable to secure a record deal for Nightbreed, Ka was feeling adrift. He enrolled in, then dropped out of, a graduate program in education, and wasn’t sure what he wanted to do with his life other than knowing he wanted to give back. The Fire Department provided the community and camaraderie he needed.

“It was a different environment for me,” he says. “You how some people join the military and it gives them structure? This was in that same context, so I appreciate and I love the shit. Sitting down in a firehouse and eating at a table with a bunch of brothers? I never did that before. I was learning how to communicate better, hearing different stories and experiences. As a writer, it’s you and your pen and paper, with no one around, in silence. You become accustomed to being in your head, and it’s lonely sometimes. [The Fire Department] forced me to be around people.”

Ka rose through the ranks quickly. According to a longtime friend named Scar, he had disappeared when he was studying for his entrance exams, then scored high on both the physical and the written portions of the test. The performance was prodigious, but when I ask Ka about it, he responds with modesty. “There was dudes that was smarter than me,” he says. “My family just was proud of me that I was moving up in the ranks so fast. You know, hood law is like ‘Yo, Ka is shooting up! He only been on this long and he’s this, that, and the third!”

By 2003, after a few years of his waning interest in rhyming, Ka quit rapping. “I dedicated my life to fucking being an MC, now I’m a failure? That shit is crazy!” he says. “But my age started getting up there. It was a diss like, ‘Ayo, you're a 30-year-old rapper.’ It was disrespectful, but I bought into that. I was just tryna not be a 30-year-old rapper.”

Leaving his art behind wasn’t so simple, though, and after two years of silence Ka decided to pick rapping back up. It was his lifeblood; he was heartbroken to have it out of his life. “I was very sad,” he says. “I felt like I honed a skill for so many years for absolutely nothing. And when I saw that the lyrical aspect of hip-hop was diminishing, it left an even bigger hole. I needed to fill it, to record to fill the void for myself and many others that felt the same.”

His wife, Mimi — who’d gone from the radio station to become the editor-in-chief of Vibe magazine, and now works as creative director of Pharrell’s media company iamOTHER — was the one who encouraged him to return to making music. Apart from music, they’d built a life together. They own a home together, and though he has no children of his own, Ka parents many people, just like his father did: his baby cousin Shania and his godchildren Ashley, Tyrone, and Chase (ages 21, 14, and 4 respectively).

Mimi and Ka officially got together the same year he quit rapping, and at first he kept his aspirations a secret. “I was leery of introducing her to it: everybody and their mother rhymes,” he says. “Just because you cook doesn’t mean you’re a chef.” But eventually, it came out. She told him that it wasn’t about a record deal, but about him finding joy in his art — which, as an industry insider, she judged to have merit. “She obviously knows music,” he says. “She was the first one to put Lil Wayne on the cover; this woman knows hip-hop. So for her to say: ‘Yo, no, you good,’ it was like, ‘Word? Don’t just say that because you like me.’ It made me feel good, a real writer telling me as an artist that I’m of worth. It was the first time I heard that,” Ka says.

Ka released his debut solo album, Iron Works, in 2008, and it wound up in the hands of none other than GZA. Word got back to Ka that the Wu-Tang Clan member wanted to collaborate, and he wound up with a guest feature on the track “Firehouse” from GZA’s Pro Tools. Ka hasn’t slowed down since.

Rather than holding him back, firefighting gives Ka’s music career clarity of purpose. He is basically a one-man enterprise, single-handedly mailing out his own CDs and records, finding his own beats to sample, and working with one engineer to put out his work. He knows Stamps.com backwards and forwards, and fills out each customs form for international orders himself. All of his CDs are $10, with vinyl copies at $20 — the height of DIY accessibility.

“I record very different from a lot people,” he says. “They come into the studio to bullshit, you know. I worked overtime for this money, it’s blood money. I do a 12-hour studio session.” As a firefighter, he spends 24-hour shifts at the station, and by comparison, staying alert for 12 — what might be a near impossible challenge for most people — is par for the course. “When I’m in [the studio], I haven’t been in for over a year, usually. So I get as much done in that first session as I can, come back do another 12-hour clip, go home, listen and figure out what I need to repair.” Ka records at The End, a Greenpoint studio that’s right on the water, with views of the entire Manhattan skyline. Chris Pummill, his engineer, jokes that Ka has never been up to the roof, easily the building’s best feature, because he is so laser-focused when he works.

With each new project, Ka hops in his car and personally drops off CDs for his cousins and friends; the drive is somewhat of a ritual at this point. When he scoops me up on the way to deliver copies of his new album Honor Killed the Samurai for “my peoples and them,” it’s still early in the morning. Standing next to his black 2005 Honda Accord, Ka is dressed so plainly that it is easy to mistake him for a neighbor taking out the trash or grabbing the mail. Dark T-shirt, no logo, and khaki shorts. Old Nikes.

The cover art of Honor Killed the Samurai features an image of a warrior committing ritual suicide. Honor has always been a grave prospect for Ka, and when asked he underscores that his drive to “be a man” has governed many, if not all, of his choices in life. Fitting of its theme, the album samples the audiobook version of Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Inazo Nitobe, which is over three hours long. The patience required to listen to the audiobook over and over again in order to find the just the right samples must have been astronomical, but it’s not surprising: Ka says he’s spent days and even weeks crafting a single line.

A 2013 NPR review described his music as “steel poetry,” and the label fits. As a listener, you have to do a little work: Ka’s bars are dense and the wordplay is the sort that reveals a new possible meaning to you each time you listen. Overall, his sound is strongly influenced by New York’s golden age of hip-hop, from the way he uses samples from records to structure his sound to the way his bars flow. He counts Rakim and KRS-One amongst his biggest mainstream influences, though he says he’s been inspired by “a thousand MCs.” Ka’s stylistic signature is old school: a minimal, repetitive production and depressingly incisive rhymes.

But it’s what he raps about that is immediate and undeniable in its impact. His story is one you’ve heard before: he’s from the street, the block, the hood — he flips self-doubt, drugs, pain, and bitterness into something he can use to get by. His voice is flat, gravelly but zoned out, like he’s trying not to directly confront the reality he describes. His mind is firmly set on a better way of being, as the hook for the song “Just” makes this clear: I plea to treat all just, to get what we need we did what we must.

“This ain’t just for me,” Ka says. “I want my peoples to be represented in this hip-hop shit because they loved it as much as the next man. It didn’t come our way, for whatever reason. That’s why I take so much time with my shit, I know that the people I was around was some of the best MCs. I had a lot of weight on my shoulders,” he says. His old partner in Nightbreed Kev’s name is pressed into the Honor vinyl, and when Ka mentions him, he tears up. “He was ill, he was so dope.” Ka can’t believe how sad and ironic it is that despite living through the violence of their neighborhood growing up, Kev died in a car accident. “That shit is wack, man,” he sighs.

With Ka at the wheel, we cruise over the Manhattan Bridge and into the East Village, landing at one of his favorite restaurants, Superiority Burger. The small, basement-level space is tiled and bright, gleaming white. The young man who rings us up wears glasses with thick black rimmed frames. Ka recommends the house veggie burger and announces he is treating me. I help myself to some of the lemon cucumber infused water sitting in a giant carafe on the counter. Ka cares about taking care of himself, and making sure those around him are living right too.

These days, he’s something of a self-identified foodie. He’s a vegetarian who sometimes cheats, but only with fish, a fact which possibly accounts for his excellent skin and youthful appearance. He also practices good skincare: earlier, he draped a bandanna over his shaved head to protect from the sun beating down on it. He hasn’t had chicken or steak in more than 10 years. He alludes to his grown-up lifestyle on the track “Finer Things,” on which he raps that indeed, he did it all for the finer things. His standard of living, while not flashy as far as rappers go, is far from the poverty he lived through as a kid.

Ka says that when he first quit rapping, he applied himself to his day job instead. “I had to really focus. I didn’t want to be a failure. It’s a test to take, I’m going to study hard — eight, nine hours a day — so that I can move up and I can be a man of worth in this shit and respected in this field, and provide for my family and have my people proud of me. We went through a lot, so to still be alive and striving — not on drugs, not in jail, and not a menace out here, it’s an accomplishment. For me, it’s just life.”

When it comes to rappers who find success in their forties, Ka stands practically alone. “I don’t know who else took this long to get acknowledged,” he says, his voice thick. “Hip-hop is a genre that is very ageist, and it was a hard reality to come to grips with.” But he’s here now, and he’s got no plans to slow down. “There’s always better to reach for,” he adds. “I have a long road ahead of me, and I’m going to continue to do my art. I want to be that anomaly, making fire albums at 50, 60 years old. Who else has done that?”

After we finish our veggie burgers, we head home to Brooklyn. Ka stops in front of my place and glances at his watch as I’m climbing out of the car: Mimi isn’t back yet from some engagement or another, he says, and he’s got just enough time to fit in a workout.