Nolay

Arron Dunsworth

Nolay

Arron Dunsworth

Nolay is one of the most formidable lyricists in the grime and U.K. rap scene. She first broke through in 2005, announcing, “Soundboy, I can have your guts for garters” on the searing “Unorthadox Daughter.” Together with her collective Unorthadox, she continued to drop tough-talking street tracks like “No Help No Handouts.” While many of her grime peers in the mid-’00s went on to release more pop-oriented music with major labels, Nolay turned down deals in favor of staying independent, and has remained so ever since.

Every release from Nolay in the intervening years has been tough-talking, but on her 2017 album This Woman, she opens up more than ever before on topics that matter to her: sexual harassment, misogyny, and domestic violence. The record has the fearsomely competitive attitude of grime, but the strength Nolay draws on comes from a unique place: the deep well of strength that women, and victims of abuse, must draw on to overcome these obstacles.

This Woman highlights how vital it is that women have a space within grime and U.K. rap to make these often marginalized experiences more visible. Over the phone from her home in west London, Nolay told The FADER about how she overcame sexism to earn her place as a respected figurehead in the scene, and why she’s ready to talk frankly about these issues now.

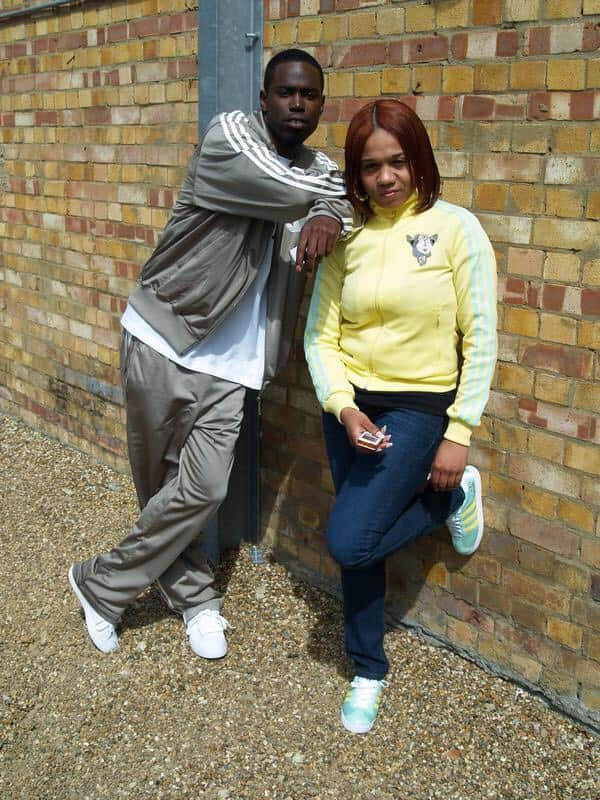

Nolay in 2005

Sam White

Nolay in 2005

Sam White

NOLAY: Female MCs feel they have to fight that much harder to get themselves heard. At my first proper rave, I was onstage with Ghetts and Crazy Titch. I was in the middle of them, and [Crazy Titch] kept passing the mic past me. I felt at that moment, that was sexism. If that was a male MC that he was acquainted with, I don’t feel like he would have [ignored him]. I can’t say that Crazy Titch doesn’t respect me — as time went on, I battled through. But with the males within this scene, it’s more of an underlying sexism. They’re not very blunt with it; they won’t say it, but you can see it in their actions.

I dated one or two MCs, and I started to notice this pattern. They were insecure about my art. They were trying to control me and break me down, and I realized it was because I’m really good at what I do. It sounds big-headed, but that was just the truth. It’s like a group of guys playing football, and a girl runs onto the pitch and starts tackling them or playing better than them. They get annoyed, and because of their ego, they find it quite hard to hide. When I started to notice that, I learned that I have to be quite cutthroat in this industry, especially as a woman.

With female acts, there can always ever only be one. That kind of mentality doesn't make any sense. I have always been competitive, whether [the opponent is] male or female. But [the media] tries to pit women against each other. [Interviewers] will say, “Do you think you are the best female? Do you think that you are a top five female?” That’s one question that I hate. It’s like, “No, I feel like I’m a top five lyricist, male or female. I’m the best.” I used to be described as “the female version of Ghetts.” How do you know Ghetts isn’t the male version of me? Ghetts wasn’t with me when I was writing my bars, he didn’t teach me how to spit, or how to perform in front of thousands of people.

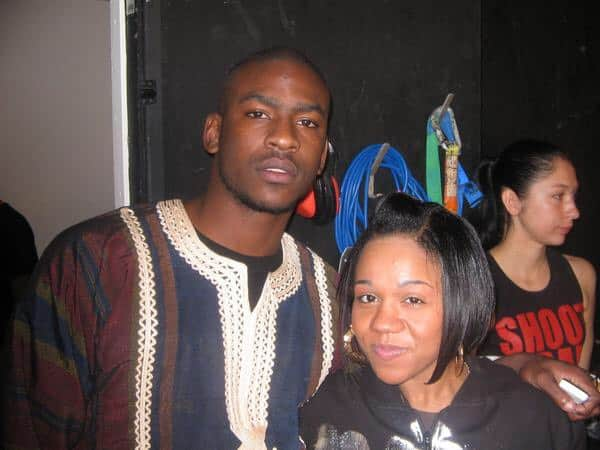

Nolay and Ghetts in 2008

Courtesy of Nolay

Nolay and Ghetts in 2008

Courtesy of Nolay

Nolay and Skepta in 2007

Courtesy of Nolay

Nolay and Skepta in 2007

Courtesy of Nolay

I also hate all-female remixes, because of the idea of having a “male version” and then a “female version.” Why is there a female version separate — is it because you feel that we are not good enough to be on the track with you? Or are you scared to have us on the track with you? I feel like [by doing women-only remixes] you are allowing the males to pigeonhole you without even realizing it. For me personally, girl power is saying “No. You can put me on the track with you, or I am not going to do it at all.”

What’s helped me get through is not giving a fuck. Being oblivious to people’s opinions, and remaining thick-skinned. The turning point was when I released “Netflix and Pills” [in 2016], which is quite dark and personal. Life shouldn’t be spent caring about what other people think of you. Once I started thinking in that way, I became so free with my art.

I have come of age now. Coming up in the scene, I was aware of sexism and misogyny, but I feel like as I’ve got older it's become more apparent to me. Now, with everything that is going on, Trump [talking] about grabbing women by their pussys...I just wanted to speak my mind. I just went into [This Woman] knowing I wanted to make women feel empowered. I don’t think [listeners] are used to me owning myself sexually, I’ve never done that previously on any of my tracks. [Before,] I was cautious, because men will sexualize you and treat you as an object. I wanted people to see me as a lyricist. But now I’m speaking up.

“I felt like I needed to use my platform to talk more about something important. One in four women are affected by domestic violence. Nobody is talking about it, and it’s one of the biggest killers for women.”

I felt like I needed to use my platform to talk more about something important. As a victim of [domestic violence] in the past with no one to turn to, I thought to myself, Why don’t I put something out there that people [in that situation] can draw strength from? One in four women are affected by it, two women are dying every week because of it. Nobody is talking about it, and it’s one of the biggest killers for women.

I wanted [the “Dancing With The Devil” video] to be full-on. When I released pictures from behind the scenes, there were comments like, “this is a bit extreme.” But this is what happens. If two women are dying a week, how do you think they are dying? From a light slap? It is extreme. I said to the director that I wanted it to be this way. The goal was for ladies going through [abusive relationships] to watch it, and feel a light bulb switch on in their head. Like, Wow, he is not going to change. I had one women message me [after watching the video] saying, “I am finally going to file for divorce.”

I’m working on a documentary with the BBC. It’s about empowering girls through music. There were ladies involved in this that have attempted suicide, that come from abuse, that come from pretty rough backgrounds. I took them to the studio, let them express themselves, and wrote with them. It’s quite an uplifting documentary, because although it’s pretty dark in the parts where they’re talking about what they have been through, it does end on a hopeful note. I want all women to watch it and be like, Yeah, that’s me. There is hope for me.

Nolay in 2006

Courtesy of Nolay

Nolay in 2006

Courtesy of Nolay