How Mr Mitch’s Delicate Grime Productions Challenge Stereotypes of Black Fatherhood

The producer explains how his intimate new album Devout is a tribute to the importance of family.

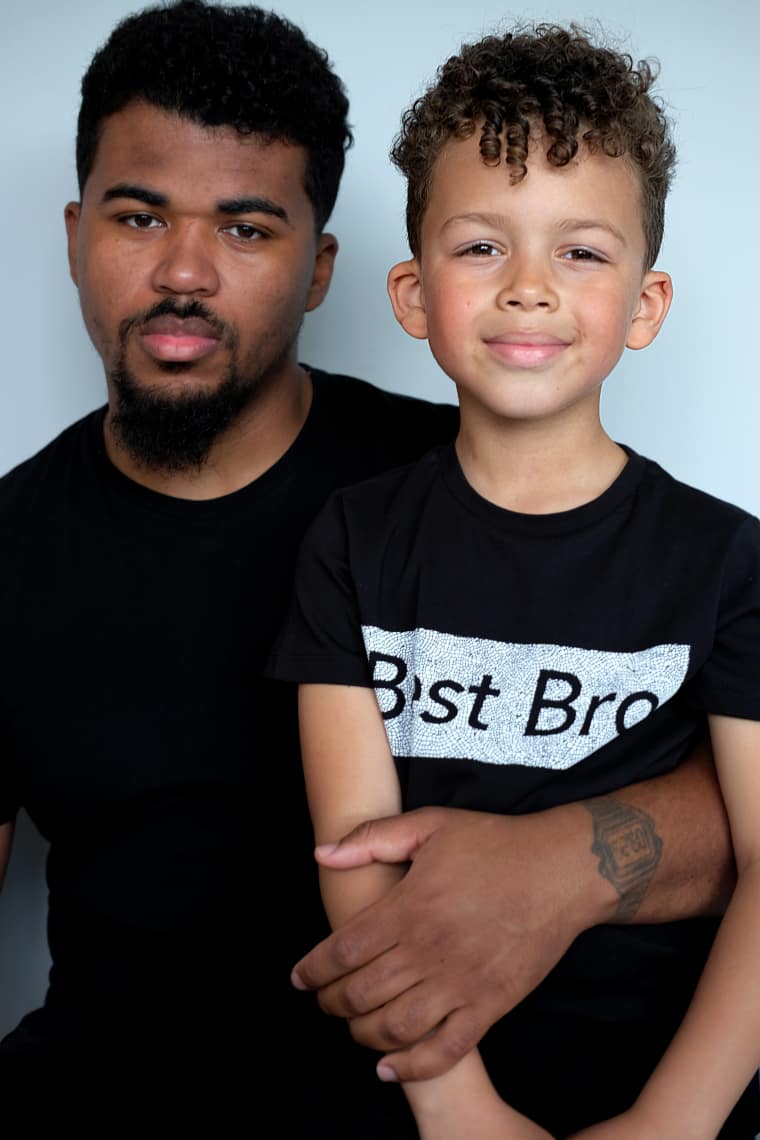

Miles Mitchell (a.k.a. Mr Mitch) with his sons Oscar (left) and Milo (right)

Educating Mummy

Miles Mitchell (a.k.a. Mr Mitch) with his sons Oscar (left) and Milo (right)

Educating Mummy

Grime has long been renowned for its noise and bravado, and MCs celebrated for how fiercely they can battle. Mr Mitch (real name Miles Mitchell), though, exists on the periphery of the more combative aspects of the scene, producing a softer form of instrumental grime that softens the barbed edges and dissolves the raw machismo of the genre. Mitchell's earliest 2010/2011 releases, on Butterz and his own label, Gobstopper Records, fit easily into the traditional grime mold: flat, icy synths set against clipped percussion, albeit with his trademark ear for melody. But with the release of his “peace dubs” in 2013, produced in response to the “war dubs” of producers in clashing wars at the time, that Mitchell began honing his altogether more delicate sound.

Devout, his second album for Planet Mu, is his most personal release to date: he began work on it when his partner became pregnant with their second child. “It just felt right to focus it around fatherhood or family life, because that was all that was on my brain at the time,” Mitchell tells me over the phone from south London. With the kids fast asleep upstairs, he speaks quietly, careful not to raise his voice on a school night. Devout is the first record on which Mitchell has sung, and also features samples of his two children, six-year-old Milo and 10-month-old Oscar. The glassy synths of his 2014 debut Parallel Memories have been replaced by warmer textures, as Mitchell and a host of collaborators, including grime MC P Money and singer Denai Moore, explore the essence of love and family life in London.

Mitchell speaks quietly but with a sure sense of himself. Looking ahead to Devout's release, he opens up about his own family, the place of fatherhood in the grime scene, and his aim to challenge the troubling stereotypes of black fathers in the media.

This is the first time you’ve sung on a record. Why now?

It's the first time I've actually had the space and the confidence to do it. Domino Publishing have a writing room, so I had the opportunity to go in there and have some time. It was quite a secluded little area and I felt quite comfortable in there. As I was making the music for the tracks, the words just came naturally. As I recorded it and made [the lyrics] up on the spot, there was no way I could have ever given those beats to anyone else, because it was so personal to me. I pretty much had my eyes closed the whole time I was singing them.

Where did the samples of your kids, Oscar and Milo, come from?

I found this video Milo made on his iPad of him singing along to some song, and the extended version of the video goes on to him talking about missing one of his friends from school. The recording of Oscar is from when my partner recorded him, and that was the first time he actually said "Dad." Right at the end of that intro track, he kind of says it. Maybe this is my dad ears wanting him to say it, but it sounds like it to me.

Fatherhood isn’t a widely discussed topic in grime; at least not in the positive way you present it on Devout. Were there any depictions within the genre you were drawing on?

It wasn't so much within grime, it was more within black culture and the black community and the media. I always seem to have been presented with this image of dads who aren't around, especially within mixed-race families. My partner is white, and you get a lot of the casual jokes about mixed-race babies on the estate and their dads not being around. It seems like it's part of the culture to joke about that kind of thing. I'm not saying it doesn't exist — but there are many dads who are still around doing their job. As I made these tracks, I felt like it was important to take note of that. If all we’re doing is talking about the [dads] that aren't doing their job then that's all we're gonna imagine that there is — and that's gonna become normal.

Mr Mitch and his son Milo

Educating Mummy

Mr Mitch and his son Milo

Educating Mummy

"I always seem to have been presented with this image of dads who aren't around, especially within mixed-race families...but there are many dads who are still around doing their job. I felt like it was important to take note of that."

Did you see Atlanta? That show featured a couple who weren’t together per se, but were completely committed to their roles as parents.

Yeah, exactly. And I'm not saying that every man needs to stick with their partner for the child's sake. What I'm saying is, men, in the relationship with the mother or out of the relationship with the mother, are doing their jobs as dads and they need to be represented. I do see [positive images of black fathers] on Instagram now, with different MCs either taking pictures with their children or mentioning their children. It's nice to see, because there's other people who hide away that they're a dad, or they almost see it as something that goes against their character as an artist.

Are there any artists in particular you’re thinking of?

I see Giggs on Instagram quite often with a picture of his daughter. He never reveals her face or anything, but he's showing himself as a caring dad but still manages to maintain this image of the street music guy. It doesn't weaken his image to be seen as a good dad. And Ghetts is another one I've seen. And P Money — the reason I got him on [“Priority”] is because I've heard him speak about his son in the past. I saw him do a 1xtra Live Lounge where he talks about his relationship with his father, and how that was strained, which is the reason he's treating his son in a certain way.

Do you think there’s a pressure on young black men to conform to hypermasculinity?

I definitely think there is that pressure as an MC, within grime or out of it, pressure that you have to be this really aggressive kind of person. A lot of it is aggression coming from a real place, [MCs are] coming from deprived areas where they're talking about violence that they see. And that's definitely a real thing. I guess that’s what comes across in the music — it's a pressure from the environment. It's made from a paranoia — in a way, it's like trying to combat fear with aggression.

Your own productions seem to move away from that.

It's not so much consciously trying to move away from the hypermasculinity, [it’s] more just presenting music that is more me. I guess growing up as a producer within grime you feel like, Right, this is what a grime club track is, it has to be really aggressive. I don't know if that's what defines grime or not, but that's not what defines me — I'm not aggressive in the slightest, and for me to make that music is forced.