A convincing case for silence

Fluxus pioneer and pianist Philip Corner is 84. And he’s still challenging audiences.

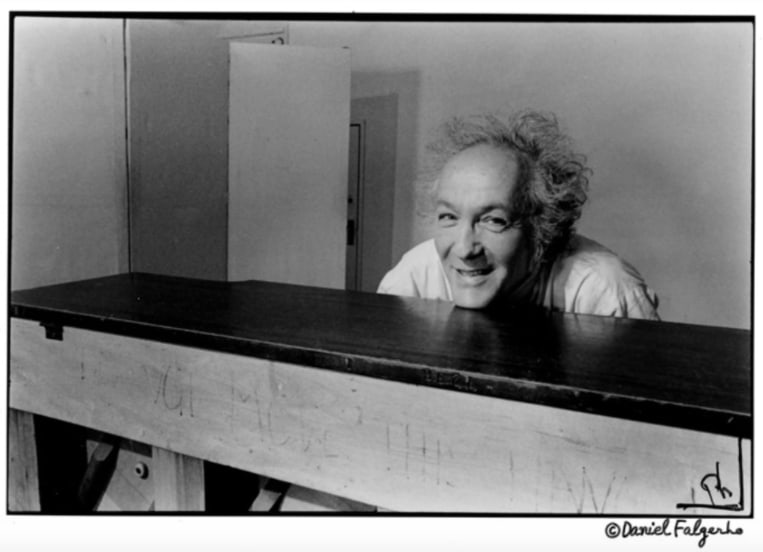

Philip Corner

Photo by Daniel Falgerho

Philip Corner

Photo by Daniel Falgerho

In New York City, where the lights shine bright every night of the week, there's always a show to go to. And if you're gonna make the effort of stepping out, then a show is generally what you expect: fanfare, action, the roar of a crowd.

But what about space for collective quiet, for communal stillness? What if a show was less about about showing and more about being?

Last night, I attended a show organized by non-profit organization Blank Forms at the San Damiano Mission, a small but ornate Catholic church just next to The Lot radio station in Greenpoint. I've been to my fair share of shows in religious venues — it's a trope of underground music, especially ambient-leaning music, one that allows an artist to wear the gravity of the setting — but I'd never experienced anything like this one.

As the audience shuffled in, an elderly man with a blur of white hair circling his head hovered at the front near a piano. Save for a few creeping whispers, the room was hushed. We were quiet because we were in a church, but also because we were in the presence of a pioneer, a very revered pioneer. A composer and pianist, Philip Corner was born in 1933 in the Bronx. He went on to become a founding participant of Fluxus, the international interdisciplinary group that pushed the boundaries of what art could be in the '60s, and worked closely with John Cage, among others.

"Thank you for this beautiful silence," Corner said with a faint smile. "There will be a lot more of it."

A few minutes later, the 84-year-old addressed the audience once more: "In reverence to the piano."

The show had began, but there was nothing to see. Having pushed the seat in, Corner stood in front of his piano with his arms outstretched. Over the course of several minutes, he slowly leaned in closer to his instrument, as if to clasp it in a warm embrace.

There was nothing to do but breathe. I felt the breeze from an open window brush my face. My fingers traced the carved flourish of the wooden pew. I could hear bodies shifting in seats, a motorcycle accelerating in the street, the trees dancing in the wind outside. I could also hear the camera of a lone photographer attempting to document every millimeter of Corner's descent towards his piano. Every click felt like a knock at the door while one is resting.

Why document this? I thought. Why not just be here with Corner and enter the space he is creating?

I noted my irritation and turned my attention instead to sensation. Breathe, listen, be still. I felt my body exhale the day's stress.

Finally, Corner's forehead hit the piano keys, which released him from his trance. He took up his seat, but those expecting music in a more recognizable form would have to wait.

He played a chord every minute or so, holding the pedal until it faded into the natural resonance of the room. Maybe 40 or so minutes into the performance, when the silences between each chord had collapsed into themselves, Corner was joined in his endeavor by his 57-year-old self in the form of an experimental radio play he recorded in 1990. A variety of electronic tones, drones, and human voices — including that of a woman who said "Observing oneself from afar" in a matter of fact tone — emanated from the speakers above our heads.

The chords Corner was playing were based on renowned French composer Erik Satie's "Première Pensée Rose+Croix", a piece he composed in 1891 that provides its own compelling argument for space and silence.

Corner's remix, if you like, of Satie is called "2 chords of the Rose+Cross by Satie...as a revelation." The revelation, for me, was that I need more space and silence in my life. And that Corner, at 84, is more punk than a lot of artists I've seen before. In experimental circles, sound is so often used to overwhelm, to bend the audience to the artist's will. What if, instead, sound — or its lack — were more often used to create a space in which to become?