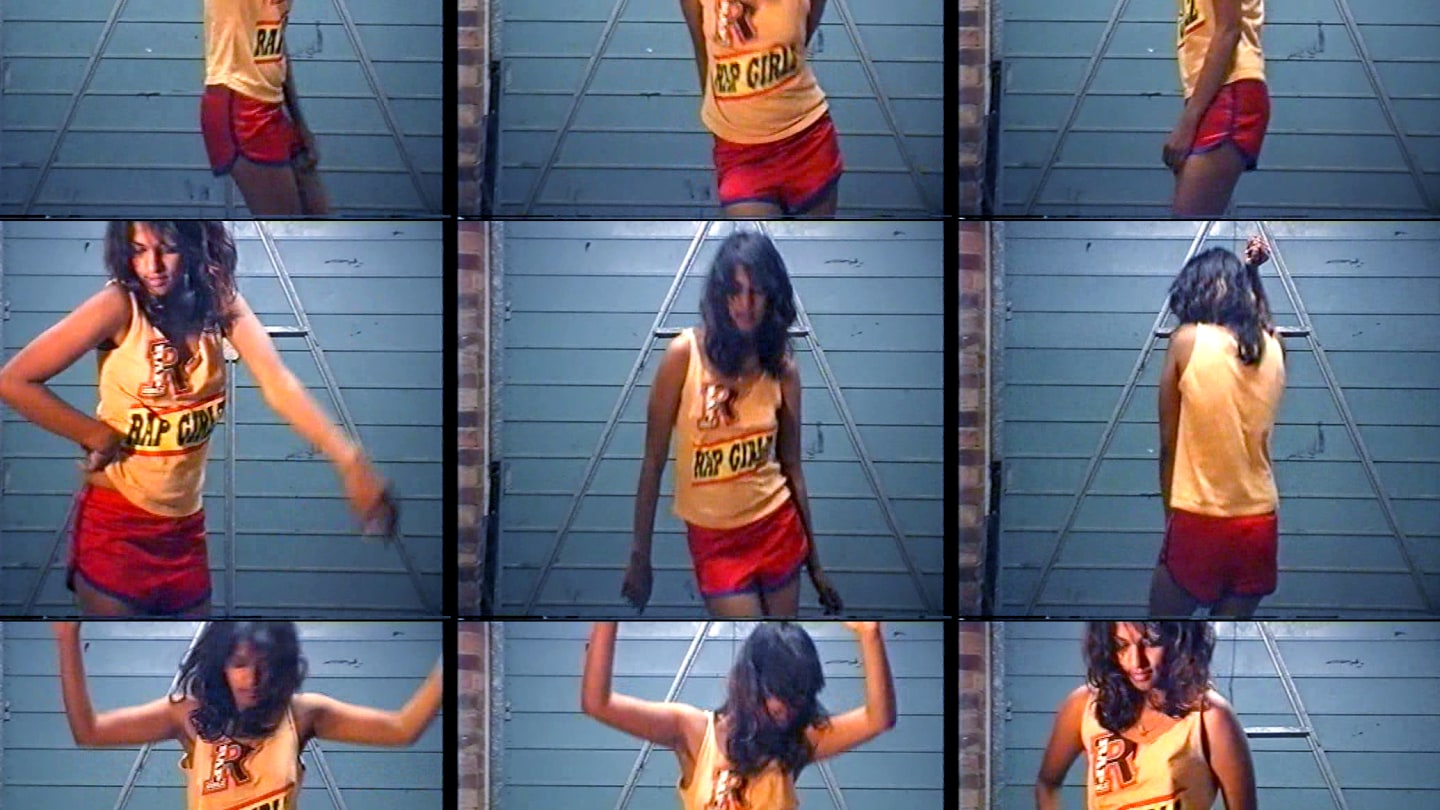

Courtesy of M.I.A.

Courtesy of M.I.A.

MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A. director Steve Loveridge sets the tone early on in his movie. “Why are you problematic,” he jokingly asks his art school buddy of 20 years, as an off-camera voice. Relaxing in her home, M.I.A. laughs his question off, though she can now point anyone asking the same question toward this clear-eyed and informative documentary.

Over the course of 90 minutes, much of which is culled from an exhaustive library of M.I.A.’s own home recordings, Loveridge offers an in-depth look at where M.I.A. comes from — and why she finds it impossible to meet some fans expectations and “shut up and make a hit.” Born in Sri Lanka before moving to London as a small child, M.I.A. broke out with her debut album Arular in 2005. But her involvement in the music industry started years earlier, in the ‘90s, when she was part of Britpop band Elastica’s entourage at the invitation of her then-housemate, Justine Frischmann.

The spirit of that heady period of Union Jack-clad British music is captured in a frantic section of the movie largely shot backstage at festivals and in hotel rooms. It’s immediately clear that M.I.A. was destined for something bigger than being a member of a team. In grainy footage from a muddy field off a motorway in England, Frischmann says Maya, as she was then known, “just can’t take not being the centre of attention.” Early signs of friction comes as Maya tells the band that not using its platform in a politically-minded way is a dereliction of duty. “You’ve got access to a microphone,” she says. “Please use it to say something.” It’s an act of foreshadowing any director would be proud of.

Where MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A. differentiates itself from the standard music doc is in its delving into geopolitics, specifically the Sri Lankan civil war, to make sense of its subject. In 2001, M.I.A., the daughter of a Sri Lankan Tamil resistance leader, returned there with a small amount of TV company money and a camera to film a documentary. What she found in her home country seemed to light a fire inside her. “I feel like I’ve opened a can of worms,” she says from her family home after speaking to her elderly grandmother about the times she has been shot at. It would be nine years after the scene was shot that the conflict ended.

The clear and calm explanation of the war in Sri Lanka is presented in stark contrast to M.I.A.’s own way of spreading news and opinion. One scene captures her tweeting a gruesome clip of a soldier being gunned down, the sort of thing more at home on LiveLeak than the evening news. M.I.A. is ostensibly showing what is really happening here, using her platform as arguably the world’s most famous Sri Lankan in a way that Elastica hadn't 15 years previous. However, you can’t help feel that her all-caps approach has perhaps hindered the delivery of her message.

What MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A. excels at is framing M.I.A.’s political beliefs, a sporadic set of ideas that has previously included vaguely-articulated support for refugees and rightfully-panned criticism of Black Lives Matter. It gives context to her story without acting as propaganda for her beliefs.

The film also highlights some of the unfair ways the media has treated her as she attempts to speak out on the genocide in her home country. A particularly egregious example is a scene in the film shows a 2009 interview with Bill Maher. In the clip, she’s keen to talk about what is happening in Sri Lanka. She is met instead with a ludicrous question: Maher wants to know why, if she was born in South Asia, does M.I.A. talk like Mick Jagger?

Comic relief comes courtesy of backstage footage from the 2012 Super Bowl when M.I.A. is told off like a naughty school child by an irate NFL employee for arguably her most infamous moment — flipping off the camera. That night was during a period, we learn, that M.I.A. wanted to get her music back on the radio. She confides in the camera her belief that "Double Bubble Trouble,” off of her Matangi album, could be a hit. It seems the stars are aligning and the Super Bowl will be the match that lights the fuse. Instead, M.I.A. literally runs away from the stadium and is later handed a $16 million lawsuit.

Director Loveridge’s personal closeness to M.I.A. does bring with it its own frustrations. It doesn’t feel like he’s in a position to challenge his friend, nor does he ever really try. This can leave what feels more like a manifesto than a movie. What he lacks in interrogation skills, however, he makes up for with access and a shared history. It’s remarkable how much footage exists from her life.

Hers is an explosive story of immigrant life in 1980s Britain, political activism in the age of celebrity and the internet, and the diasporic explosion in music in the 21st Century. People with an interest in either of those things will get something from MATANGI / MAYA / M.I.A. It is a smart and even-handed presentation of a gifted yet frustrating star whose every move remains captivating. In terms of a definitive statement on who she really is, it may be up to M.I.A. deliver that herself.