Nik Freitas

Nik Freitas

As teenagers, we’re told to rein in our feelings to move through the world more productively. Love knocks the Earth from its axis, anger threatens to burn it up, sadness places us at the center of its galaxy, with no one else in sight. Those feelings dig deep canyons into the surfaces of our hearts. The rivers that run through them—painful, blissful, or a mixture of both—are difficult to dam, taking not only the world's overwhelming din but a final surrendering of hope to stop their flow. As adults, it takes a lot of strength to keep dipping our toes in.

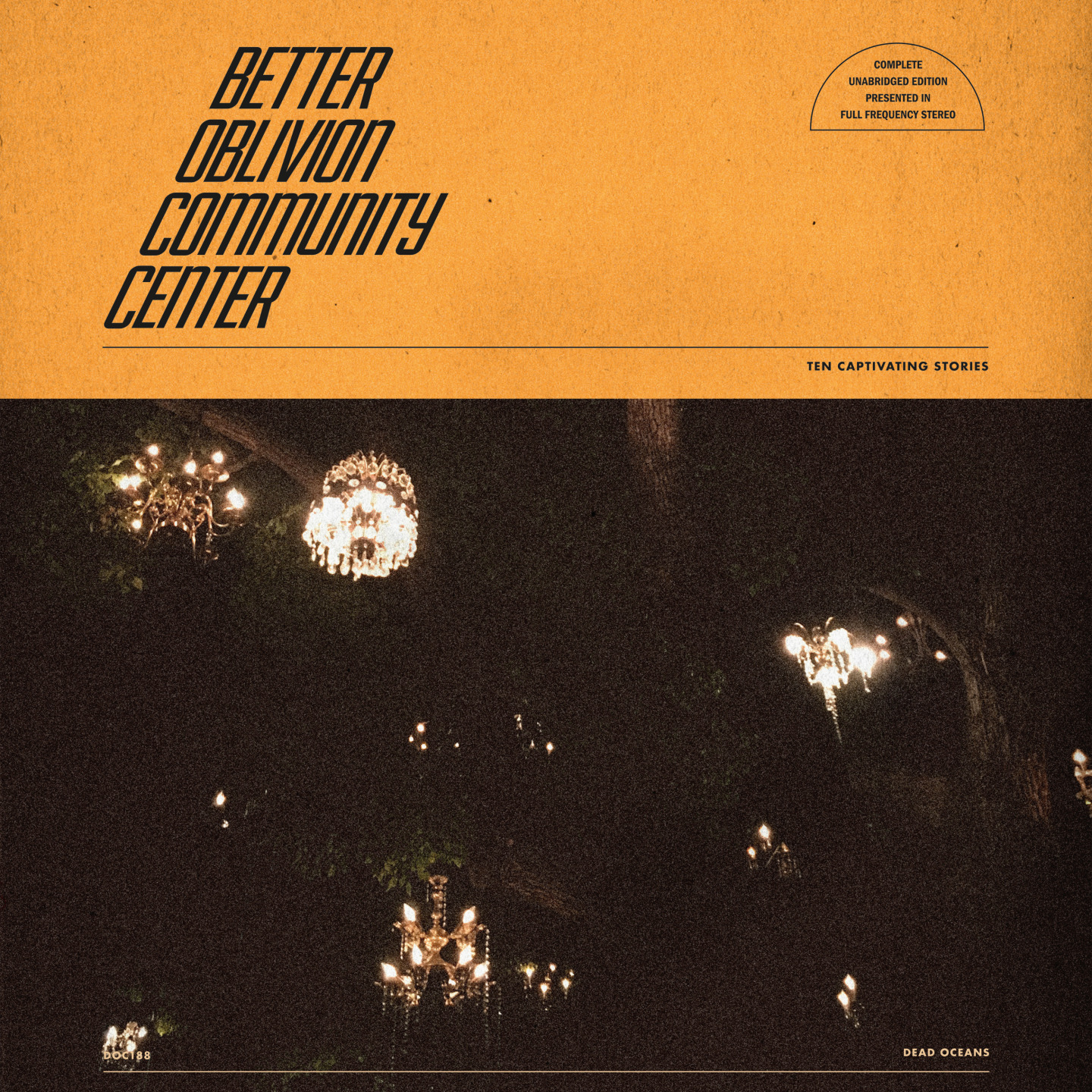

Time is on my mind lately—specifically, the way our perception of time changes due to variables ranging from circumstance to state of mind. As capitalist forces continue to demand more and social media remains hell-bent on insidiously leeching time away, taking ownership of our time—slowing it down and using it for enrichment—is a radical act. Conor Oberst can remember a world where time seemed to erode more slowly; Phoebe Bridgers is part of a generation waking up to how much time has been stolen from it and fighting to take it back. As Better Oblivion Community Center, their collaborative debut gives the gift of intimacy; it reminds that our time is worth holding onto, the connections we make when we use it wisely are invaluable, and all our big, sloppy feelings are valid. As their bus bench ad reads, the services the band offers include “assisted self-care,” “free human empathy screenings,” and, “chosen family therapy.”

In the summer of 2005, I was 17 and rambling around my hometown’s dusty core as time crawled through the Prairie heat, nothing in mind but seeking out the next big feeling I could come by or create. Miraculously, I found someone else who wanted to build those feelings along with me—even though neither of us really understood them—and we floated through the city, making out in alleys off the main drag and trespassing just to lay down by the river in hidden places, trace constellations, and drink king cans of cheap beer. We were indomitable and untraceable.

She had no cell phone and I despised mine—a junky silver Nokia my mom gave me when I started working downtown at a call center—to the point that it was never on. Whenever we made our escape to the cool, blue light of her mom’s basement, the phone didn’t exist, buried inside a pocket in a heap on the laminate floor. The rest of the world didn’t exist, either; it was just us, safe from everything but each other and slowing time down with spins of Bright Eyes’ I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning. For a little while, every day felt like the first days of our lives, our connection to each other buoyed by our disconnection from outside voices.

“My telephone, it doesn’t have a camera,” Phoebe Bridgers sings on “Didn’t Know What I Was In For.” “If it did, I’d take a picture of myself. If it did, I’d take a picture of the water, and the man on the off-ramp holding up the sign that’s asking me for help.” Without the technology, there’s no real option to engage these thoughts superficially on impulse and then ignore them. They’re just there, hanging in front of her.

Bridgers coasts through observations that go hand-in-hand with the disenchantment that happens as time pulls back certain curtains: people lie, our battles with institutionalized systems feel futile, you can’t escape yourself. But there’s a quixotic fight in her voice despite the weight of her words. Finally, she confides she listens to white noise to fall asleep, to drown her own thoughts out, to not think about “how living’s just a promise that I made.”

Oberst has spent decades swimming through those metaphorical rivers mentioned above, often injecting even his most cynical songs with a ray of hope. Bridgers wields a soft intensity with her songwriting similar to Oberst’s in its intimacy and imagination, but she renders her subjects in dreamier light, bathed in lushness. Better Oblivion Community Center reveals two kindred voices—one of someone whose first release came before cell phones were even commonplace, and one of a songwriter who grew up during the rise of social media—confirming the value of holding onto our time and most powerful feelings, and pushing back against the apathy that so many outside forces try to pull us toward.

But there’s no denying that, sometimes, all we want to do is give up. “So sick of being honest, I’ll die like Dylan Thomas, a seizure on the barroom floor,” Bridgers and Oberst sing together on "Dylan Thomas," over an aquatic, echoing acoustic guitar strum, admitting before a Nick Zinner-helmed feedback freakout, “If it’s advertised, I’ll try it, and buy some peace and quiet, and shut up at the silent retreat.” The wistful “Chesapeake” takes a more existential perspective; “The world will not remember, when we’re old and tired,” they whisper over the sparse tune carried by co-writer Christian Lee Hutson’s pocket piano, “We’ll be blowing on the embers of a little fire.” “Forest Lawn” imagines that fire finally extinguished, but not without room for romance: “Used to say you wanted to end up in Forest Lawn, the two of us side by side, asleep while the teenagers drink ‘til dawn,” they sing together before Oberst pleads alone, “Please tell me it’s true.”

“Exception To The Rule” carves out space with aggressive synthesizers, a moment that feels out of step with the rest of the album, stuck between two mostly bare, acoustic songs. It’s not chilly, but it lacks the same blanketing warmth of the rest of the album, something largely owed to simple, earthy production. But its main source is the intertwining comfort of Bridgers’ and Oberst’s voices—his shaky and impassioned, hers like a breathy balm—that conveys the depth of their creative connection.

That connection creates a sound, too, that is more than the sum of its parts. Oberst has always leaned toward grandeur, more often than not diving completely into it. Bridgers’ talent for making small moments—folding towels, watching the freeway, setting off bottle rockets—sound life-altering and significant balances out any epic urges. It's almost as if epicness is anathema to the Better Oblivion Community Center mission; the songs are solid but just a touch fractured, mostly folky and heavy-hearted, prone to experimental ambient flourishes or noisy guitar breakouts. It sounds lovingly scrapped together in peaceful environments, by friends with DIY inclinations and nowhere else to be.

“My City” feels like a spiritual cousin to “Didn’t Know What I Was In For,” following a narrator restlessly walking through their town, thinking back on memories with someone they loved, wondering what happened to them. “Little spells of forgetfulness, little sounds that are shrill and urgent, little insects that sting as they come and go,” they sing, blurring the line between memories and observations, but concluding they are “little moments of purpose.” It has the same upbeat melancholy that comes from going home again and exploring it anew as a geography of memory. The song ends awash in sound, with a cathartic climax more satisfying than what real life usually affords such a trip: “Risk it all on a game of chance,” their voices rise, “chasing love like an ambulance.”

Last year, I visited the friend I’d drifted through the riverbanks and alleys of my hometown with when I was 17. Before we said goodbye, we stood in the gravel driveway of the cabin she was living in—miles from the city, deep in the woods, with no reception—and marveled at the connection, different but the same, that we still felt some 13 years later, lamenting time lost. But it wasn’t really lost. The connection was proof of that. Better Oblivion Community Center’s final song, a cover of Taylor Hollingsworth’s “Dominos,” meanders more than the others. It concerns itself with wasted time — trading sleep for drinks, talking to angels, getting stoned, visiting “wild purgatory,” the kind of things as wasteful to spend your time on as listening to records in a basement. It’s not actually wasted time, of course; we’re all bound for oblivion. But together, on our own time, we can make it better. “All you gotta do is follow, and if you’re not feeling ready,” Bridgers and Oberst sing in harmony, “there’s always tomorrow.”