Photo by Brenda Chase Online USA, Inc

Photo by Brenda Chase Online USA, Inc

Everybody who was there says they made the Makaveli album in a week. Pac wanted it to be “only for the swap meets,” no video, no single, no commercial release at all. He was marching around the studio compound in Tarzana, shirtless so you could see his bullet wounds, explaining to his friends that he was going to die. He grabbed producers from what other Death Row artists had dubbed The Wack Room –– no one picked the beats that came out of there –– and bent them to his will, telling them where to place kicks and snares, humming bass lines, demanding the beats be constructed right in front of him. He laid all his vocals in one take and he demanded that everyone else do the same. If you were in the room, you were expected to write to the beat; if you stuttered when Pac stepped out of the booth and pointed at you, you weren’t on the song.

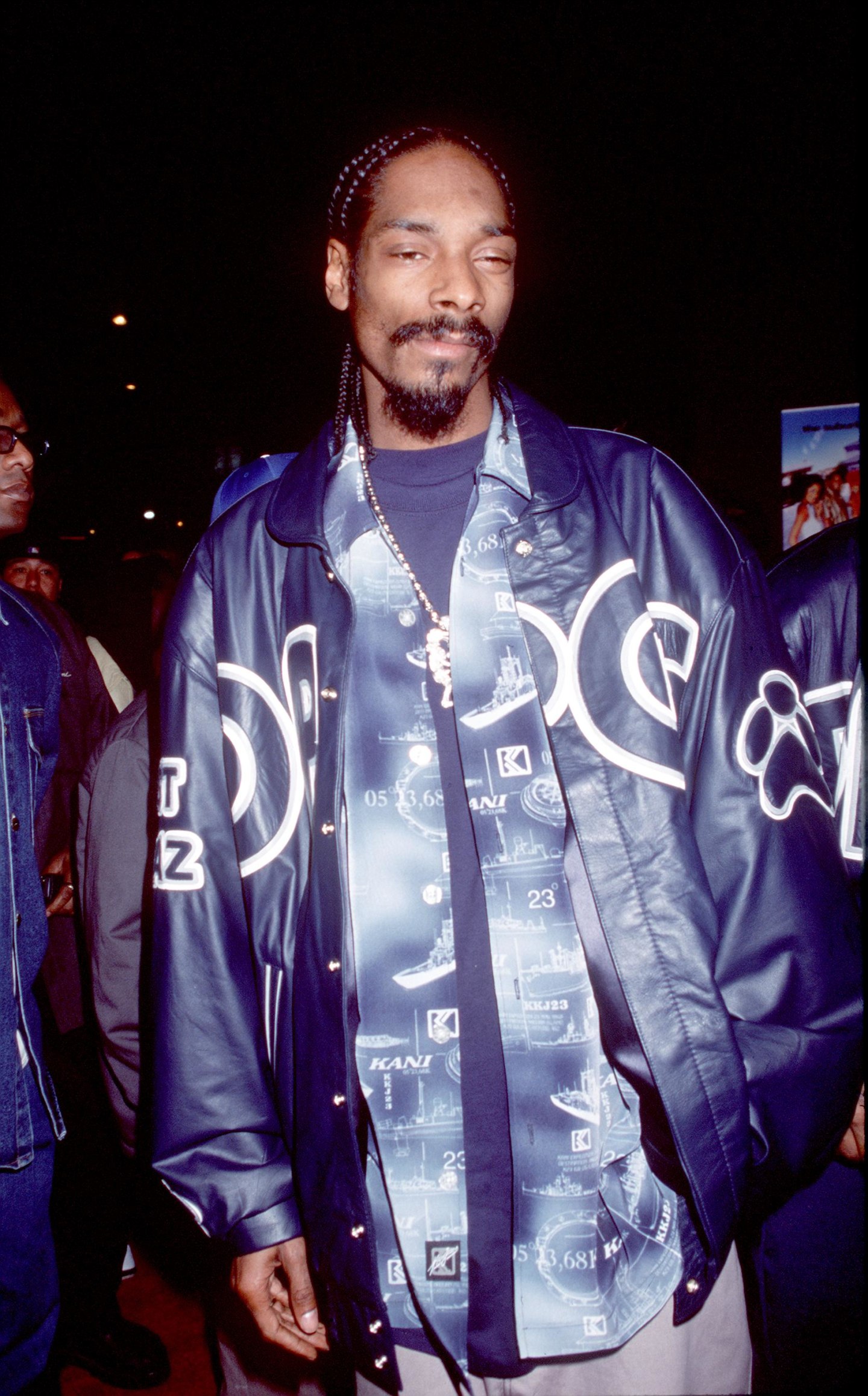

In the room next door to Pac’s in Tarzana, Snoop Dogg was also locked away and tasked with crafting a masterpiece’s sequel –– he was trying to top what was, to that point, the most monumental rap debut of all time. There was almost no interaction between Snoop’s camp and Pac’s and, according to the latter group, there was more than a little bad blood. Later, Snoop would insist in interviews that any tension between he and Pac was the result of hangers-on at the studio and the legal and physical minefield that was life under Suge Knight, all of which is probably true. But the fact was that, despite the two biggest rap stars in California were on the same label and writing and recording in adjacent rooms, they barely crossed paths.

It’s important to remember that the Death Row in the summer and fall of 1996 was almost nothing like the Death Row that had existed for the five years prior. You know the broad strokes: Dr. Dre made The Chronic during the Riots and dropped it at the end of 1992, then got to work with Snoop on Doggystyle; there was Murder Was the Case and Above the Rim and Dogg Food; there were the spectacular headlines about Suge marching into a prison in upstate New York and freeing Pac in exchange for his signature on a contract, scrawled hastily on printer paper and obligating him to albums he would not live to finish.

Musically speaking, everything on Death Row ran through Dre. Even when it was someone else behind the boards –– Daz did nearly all of the Dogg Pound album, and acquitted himself excellently –– everything on the label came from The Chronic’s rib. That album and Doggystyle (its beats fuller, more ambitious, lusher) were the platonic image of G-funk. The prospect of Dre and Pac paired with one another was tantalizing. But when All Eyez on Me came out in February of ‘96, only two of its 27 beats came from Dre –– including the deliriously unhinged “Can’t C Me,” but not including the original beat for “California Love,” Dre and Pac’s duet that announced the latter’s release.

It’s understandable that the contemporary reporting on Dre’s departure focused on the business implications, but with hindsight, his break from Suge signaled the beginning of the end of the particular kind of gangsta rap music that had gripped the American imagination since Straight Outta Compton. Some of the variables at play were, obviously, impossible to foresee at the time. But by the middle of 1997, we were in a new, shinier era. In the moment Pac held on stubbornly. The Makaveli sessions plowed ahead with the sort of bullishness that some now try to paint as foreboding, but which had allowed him to craft, in All Eyez and the new album, three discs’ worth of extraordinary material in less than 12 months. There’s been plenty of speculation about just how much Pac’s relationship with Suge had deteriorated by the summer of ‘96, but on the album itself he’s sharing his boss’s grudge: he jacks the “No Diggity” beat for “Toss It Up,” where he questions Dre’s sexuality and whether he’d be allowed back in Compton, and ends “To Live and Die in L.A.” with another crack about “gay-ass Dre.”

The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory came out on November 5, 1996. Seven days later, Death Row issued what should have been another blockbuster.

Unlike its predecessor, Tha Doggfather is bloated, unshappen, and confused. Its star is still an obvious, iridescent talent, but it’s difficult to see how any of the songs included on the sophomore set would have cracked Doggystyle; it’s harder still to come up with a second album from a celebrated rapper that was so widely considered a misfire, without being some sort of radical stylistic departure or deliberate shunning of expectations.

The album is a failure in just about every sense: commercial, creative, competitive. It’s also fascinating for a number of reasons. First, it’s a document of what an extremely gifted artist was capable (and, just as often, not capable) of doing when his work environment was radically altered. Second, it came after the end of a long and grueling murder trial, which dovetailed with the rise of gangsta rap (and of Snoop as one of its stars), the residue of which can be seen and heard here, with warnings to kids who want to grow up and imitate him. Most importantly, Tha Doggfather is mysterious for the simple fact that it wasn’t a dead end –– what changed following this record; what did Snoop hear when he played it back; how did the machine keep moving?

On February 20, 1996 –– seven days after All Eyez on Me hit stores –– Calvin Broadus Jr. was acquitted of his murder charge. He’d been fighting the case since midway through the Doggystyle sessions, when he was arrested and charged alongside his bodyguard. The bodyguard, McKinley Lee, admitted to shooting and killing a 20-year-old man, but successfully argued that he and Snoop, who was driving the vehicle they were both inside, were acting in self defense, as the victim was reaching for the gun in his own waistband.

At the time of the acquittal, Snoop was just over two years removed from Doggystyle’s release, and just over one year from the short film Murder Was the Case and its accompanying soundtrack — a direct response to his legal situation, which had the kind of urgency you can’t conjure out of peace times. Daz and Kurupt’s album as Tha Dogg Pound, Dogg Food, hit No. 1 on Billboard in ‘95. Snoop was on “New York, New York” from that album and “2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted” from All Eyez, where Pac is the force and Snoop provides the finesse. He was everywhere.

It is impossible to understate the psychological torment a murder trial might take on those involved, but it’s not hard to explain how a fickle public might move on to the next batch of headlines. Pac’s mania sucked the air out of the room at Death Row, but ‘96 was also full of blockbuster rap records from major artists, celebrated debuts, and sleeper hits that would gain traction over time: It Was Written and Stakes Is High, Hard Core and Hell on Earth, Reasonable Doubt and ATLiens, The Score and Ironman. Snoop’s second effort stayed afloat through sheer inertia; only the two Pac albums sold more in their opening weeks, and it was eventually certified Double Platinum (this period was not quite the apex of CD sales for rap albums, but it was the Wild West compared to the present, or really to any time since the Iraq war). But in retrospective looks at rap in 1996 –– one of the most mythologized years in the genre’s history –– Tha Doggfather isn’t maligned or picked apart. It’s simply written off.

Conventional wisdom would say that it starts with the beats. Dre was strictly forbidden from anything Death Row after his departure, of course. The production on Doggfather is, on the whole, thinner and smaller than what Snoop had rapped over on his debut, which colored in what The Chronic had initially sketched. Snoop, perplexingly, decides to address this head-on in the skit at the beginning of “Freestyle Conversation,” when a friend tells the rapper that, given Dre’s departure, the rumor is that Snoop’s new beats are going to be “delicate.”

“Delicate?” Snoop asks.

“Beats?

So that’s what makes me now?

Man, I don’t give a fuck about no beat.”

That wasn’t true; one thing that’s made Snoop great, from the early years of the Clinton Administration through the present day, is how musical he is, how his voice rises to glide with or cut through the beat. He’s done this over funk bass lines and steely synths and Beats by the Pound. Unfortunately, the beats Snoop is left to grapple with here (from Daz and DJ Pooh, among others) pale in comparison to most of what he had touched before, Dre-produced or otherwise. There are plenty of slightly above-replacement level funk cuts, but little that burrows into the brain, and nothing that breaks new ground, for Snoop or for California.

Tha Doggfather’s successes are songs like “Up Jump tha Boogie,” where Snoop and Kurupt get a little mean and extremely fun over Zappian funk. Hearing Snoop’s airtight opening verse on “2001” is a clear reminder that he, more than any rapper before him not named Rakim, was able to be breathtakingly precise while sounding loose and nearly bored. But these moments are buried under layers of flab. Tha Doggfather is far from the worst offender in terms of mid-’90s rap albums with a little bit of bloat, but any enterprising playlister would be able to cut this by at least 50 percent without missing any of the excised parts.

There’s also something to be said about how Snoop’s restraint here hurts the album. About 15 minutes into it, there’s a skit where a kid comes up to Snoop and says that, when he grows up, he wants to be just like him, to which the rapper responds: “Don't let me ever hear you say you wanna be like me –– you could be a doctor, a lawyer, a football player, a Laker, anything.” What Snoop tries to do throughout Doggfather is exhibit the sort of maturation that was probably taking place in his life: he was 25 now, a father, had successfully navigated a terrifying legal gauntlet, had adjusted enough to the money and fame and constant paranoia. (His trailer on the set of the “New York, New York” video was shot at, too.) But instead of making a hard break into a new, constructed persona –– or, instead of flitting between familiar fare and songs that were radically different –– he mostly just dials his old style down to 80 percent. “Groupie” (for example) seems lifeless and rote compared to the absurd extreme to which “Ain’t No Fun” (for example) had carried the same concept one album earlier.

To be clear, there’s no sane argument to be made that Snoop should have turned in a Common album or whatever; the point is that the changes here are a series of half-steps, carried out over at least a handful of beats that would be lucky to be called leftovers from the prime Death Row albums. The effect is that, rather than exhibiting one specific kind of growth, the album tamps down its own stakes, as if Snoop’s greatest nemeses were coiffed entertainment lawyers. Maybe they were.

And yet even at his most diminished –– and there are points here, like the docile “Snoop Bounce” and the unexplainably subdued “Sixx Minutes,” where he is certainly diminished –– Snoop is a nearly inimitable rapper. His voice and fluidity are extraordinary. The most captivating moment on Doggystyle, save for the two massive hits and (debatably) “Murder Was the Case,” is his cover of “La Di Da Di.” The notion that someone could cover Slick Rick without coming off as a photocopy of a photocopy is, generally, absurd (even if it’s been done well one time since). But Snoop affects an accent that captures the spirit of Rick’s British one while still sounding 6’4” and extremely Long Beach; he has the exact concoction of absurdity and sneering flyness to pull it off. So it makes sense that he would go back to the well for Doggfather, this time swiping “Vapors” from Biz Markie and paying homage to Run-DMC’s “Wake Up.”

The ways we talk about Important rappers and their work tend to overvalue things like narrative cohesion and a very narrow scope of self-serious lyricism at the expense of any number of other qualities, many of which –– simple playfulness comes to mind –– are foundational to hip-hop. This is why the canon looks a certain way and why, when we expand it, we tend to stretch credibility to make new works fit old criteria –– Jeezy’s lyrics are misascribed triple-entendre meanings instead of celebrated for succeeding in a different mold. Snoop, fluent in nearly every facet of rap, is often at his best when he’s simply diving into a one-off experiment.

By Snoop’s account, he and Pac reconciled in an arid Vegas hospital suite. His voice appears on the album’s outro, no doubt added after the assassination. Dre is nowhere to be found on Tha Doggfather, for obvious reasons, but they’d be working together again within two years. This album is Snoop being kicked unceremoniously out into the wilderness, with it expected –– assumed –– that he would find his way back. He eventually would, and maybe the tools he picked up during these sessions would help him later on. But for Tha Doggfather’s 75 minutes, he’s still wandering.

The Defiant Ones, the four-part documentary that ran on HBO a year and a half ago, tries to further immortalize Dr. Dre and Interscope boss Jimmy Iovine but unspools in its last hours into a glossy commercial for Apple. It’s worth watching, though, for the archival footage that comes in the first half: there are extended clips of Eazy-E in a makeshift recording booth, being coached through vocal takes by a babyfaced Dre. There are also long, unedited blocs of tape from the “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang” video. Snoop sways a bit to the music, but will barely make eye contact with the camera. He mostly stares at the concrete and at the shoes whose logos haven’t been blurred out yet.

Snoop learned to rap under Dre. What was rambling and formless got tailored neatly to beats; stories about absent parents and Seagram’s gin were allowed to play out with clarity and the proper pacing. Snoop could be acrobatic as a rapper, but on The Chronic he learned how to mete out his technical wizardry in a way that made sense and had the maximum impact. By ‘99, Dre was feeding Snoop a few beats per No Limit album (N.B.- No Limit Top Dogg is a classic, and Snoop’s second-best album after Doggystyle), and Snoop was anchoring Dre’s 2001, which succeeded in not only erasing the memory of Dr. Dre Presents… The Aftermath, but in fleshing out a sound, innovative but massively popular, that was distinct from the Death Row days, but still unmistakably Dre’s.

But contrast the two in the years since 2001. Dre’s legendary reclusiveness and perfectionism have borne out in the music he oversees, which tends to be stiff, over-rehearsed, and, precise in a way that feels neither exciting nor alive. (To borrow a phrase from my friend: he has successfully “eradicated mischief.”) Snoop, on the other hand, is as good as any veteran rapper has been at tapping into both sides of his brain: he’ll make a lush, funked-out, tightly-wound album like Bush or an entirely freestyled, no-frills rap affair like Neva Left; he’ll be steely-eyed or free and goofy; he’ll make “Drop It Like It’s Hot” or he’ll make “Beautiful.”

Plenty has been written on how Snoop Dogg, once a menace standing trial for murder, has been welcomed into every living room in America, smiling next to Martha Stewart and etc. But there’s nothing remarkable about the way American pop culture hardens and softens people on a whim. We’ve been projecting ideas onto (and stripping ideals from) entertainers and athletes and ordinary people forever. What’s been remarkable is Snoop’s creative persistence: he’s got one of the most recognizable voices and faces in the world, and he’s been consistently inventive since 1992. What Doggfather –– and the decades after Doggfather –– proves is that Snoop Dogg was always going to endure, with or without a super producer standing behind him, with the celebrity machine churning in his favor or a team of prosecutors dangling him over an electric chair. He just needed time to work out the kinks on his own.