Solange’s A Seat at the Table came at a time when many were tender. Seeing Black life stripped away in graphic detail was a reality being regularly experienced on social feeds and newscasts. The nation’s first Black president was just under four months from fulfilling his second term, and a man who looked to the days of segregation as something to aspire to was on his way in. The album’s timing, intentional or otherwise, was impeccable. In A Seat’s 51 minutes, Solange set out to normalize Black women’s rage, encourage ownership within the community, and to emphasize the power in being exclusionary. The messaging was clear and, because she was so effective in conveying it, the Houston native’s listeners, when talking about work to come, seemed hellbent on equating her value to being a Voice for the people.

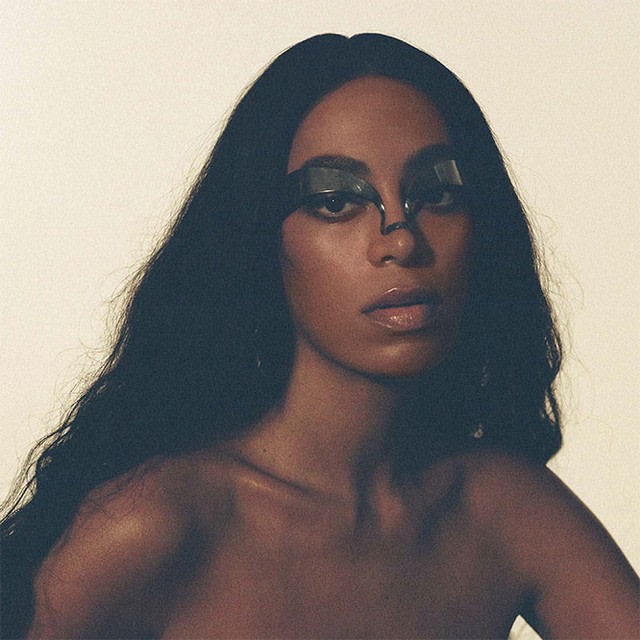

While the music penetrated, the other branches of Solange’s creativity — her live show reminiscent of ‘70s disco and funk in its stage design and wardrobe, being the face of fashion campaigns, her An Ode To performance at the Guggenheim Museum — hinted that A Seat at the Table was just one statement piece from her multidisciplinary toolbox rather than her entire mission. What’s become more evident than anything over the past few years is that she has been fine tuning her ability to travel through eras in order to present a timeless representation of Black American life. Her newly-released fourth studio album, When I Get Home, is the closest Solange has gotten to making her music fully reflect what has seemed to be a more holistic journey in her art across mediums.

Throughout the album, Solange plays around with the ways her varying influences can coexist with one another. “Down with the Clique” has the contorting synths of early funk and the hook incorporates Houston chopping of her vocals. Parts of “Sound of Rain” feel ike Art of Noise’s “Moments in Love” while at other points, she adopts conventional methods of Houston rap storytelling ( the repeating “swing on ‘em”). When I Get Home is very much a hearty love letter to the artist, producer, and singer’s hometown, but Solange exhibits that love by reimagining what the city would look like if it was constructed by her own dreams (the album’s intro is a repetitive invocation about imagination).

She isn’t alone in this kind of innovative call to her origins: late last year, her fellow Houstonian Travis Scott released his most complete album to date with Astroworld, which was set in a new, warped version of his favorite childhood amusement park. In the next state over, Boosie Badazz tried his hand at recreating Louisiana blues with Boosie Blues Cafe. Maybe this trend is a natural response to the many American cities with strong Black cultures that are rapidly changing, or it could be a nostalgia-informed urge by people who have traveled the world only to realize what they really need is to be grounded by their roots. Solange echoed that on A Seat’s “Cranes in the Sky” when she sang, “I tried to run it away. Thought then my head be feeling clearer / I traveled 70 states. Thought moving around make me feel better.”

Those who wanted a sequel to A Seat at the Table will likely be disappointed with what When I Get Home offers musically. The straightforward, and often therapeutic, themes about navigating racial microaggressions and disputes have been swapped out for abbreviated messages that require a bit more interpretation from the audience — or no interpretation at all. Tracks like “Dreams” will have you trying to figure out what “Dreams, they come a long way. Not today” really means, but by the time you start to, the song has seamlessly transitioned into the bouncy, star-studded “Almeda,” which gets complementary contributions from The-Dream, Playboi Carti, and Pharrell. Gucci Mane shows up for a jazz-tinged “My Skin My Logo” where he and Solange gas each other up for a few bars. Then, on “Binz” she sings about wanting to show up to places on “CP time” while The-Dream incorporates Sister Nancy’s flow over production partly handled by Animal Collective’s Panda Bear.

When I Get Home is significantly more playful and experimental than what the past few years have framed Solange as musically. The messaging here isn’t absent, it’s just not as comprehensive and laid out as her previous album. Instead, experimental instrumentation and the looping of much of the album’s vocals serve as ideas for the listener to ponder on and to apply to their own lives however they see fit.

The album’s visual component also fills in perceived blanks that the music leaves when it stands alone. In just over 30 minutes, the film presents futuristic depictions of women behind the decks of what seems to be a mothership, men ride horses along countryside trails, and dazzling architecture helps tell the story of Solange’s ideal world. Terence Nance of HBO’s Random Acts of Flyness (a native of Dallas) is credited as a key contributor, and when comparing When I Get Home to his work, the album begins to make much more sense as a concept. In just one episode, Nance’s show can bounce from nostalgic references to Black-centered local television programming to conventional interviews to highly-produced musicals. It caters to how we now absorb information in short, impactful spurts rather than long, drawn out ideas.

When I Get Home — the music by itself — follows that formula in how it stitches together these ideas that may not be so clear on their own but, when taken in as a unit, tell a bigger story. From its interludes to the repetitive tracks, the album continuously offers bite-sized doorways into Solange’s personal musings. Considering this, it’s also interesting that many of Solange’s aesthetics have half-jokingly been linked to ideas generated in certain corners of Tumblr that Black women once occupied because this album performs similarly. When I Get Home itemizes and flashes concepts, history, music, poetry, and information that speak to Solange in a similar way as the platform would (her customized Black Planet page also referenced this). The entire album flows like one long song — accented by cut-aways like Crime Mob's Diamond and Princess on "Can I Hold The Mic," and Houston poet Pat Parker on "Exit Scott." Consuming the conscious stream of When I Get Home feels like an infinite scroll.

What’s most exciting about stepping back and taking in all the components of this project is that it still doesn’t forecast the future of what Solange may present. A Seat at the Table was so effective at speaking to the concerns of Black folks, that people began looking to her as a healer of sorts. But When I Get Home has healing properties too, just carried out differently. Much of A Seat felt like it was a statement of resistance against whiteness or any disruptive force. This album centers Blackness, but not in a way that’s concerned with who did it first or did it better. It extends the conversation being generated by Black visual artists like Deana Lawson, John Edmonds, and Arthur Jafa, which argues that the shit Black people do in their everyday lives is just as extraordinary as when they are performing for outsiders’ gaze. The point here is that Black people do [many] things because they exist, just like everyone else. When I Get Home just shows how it’s done, rather than telling.