The Bardos

The Bardos

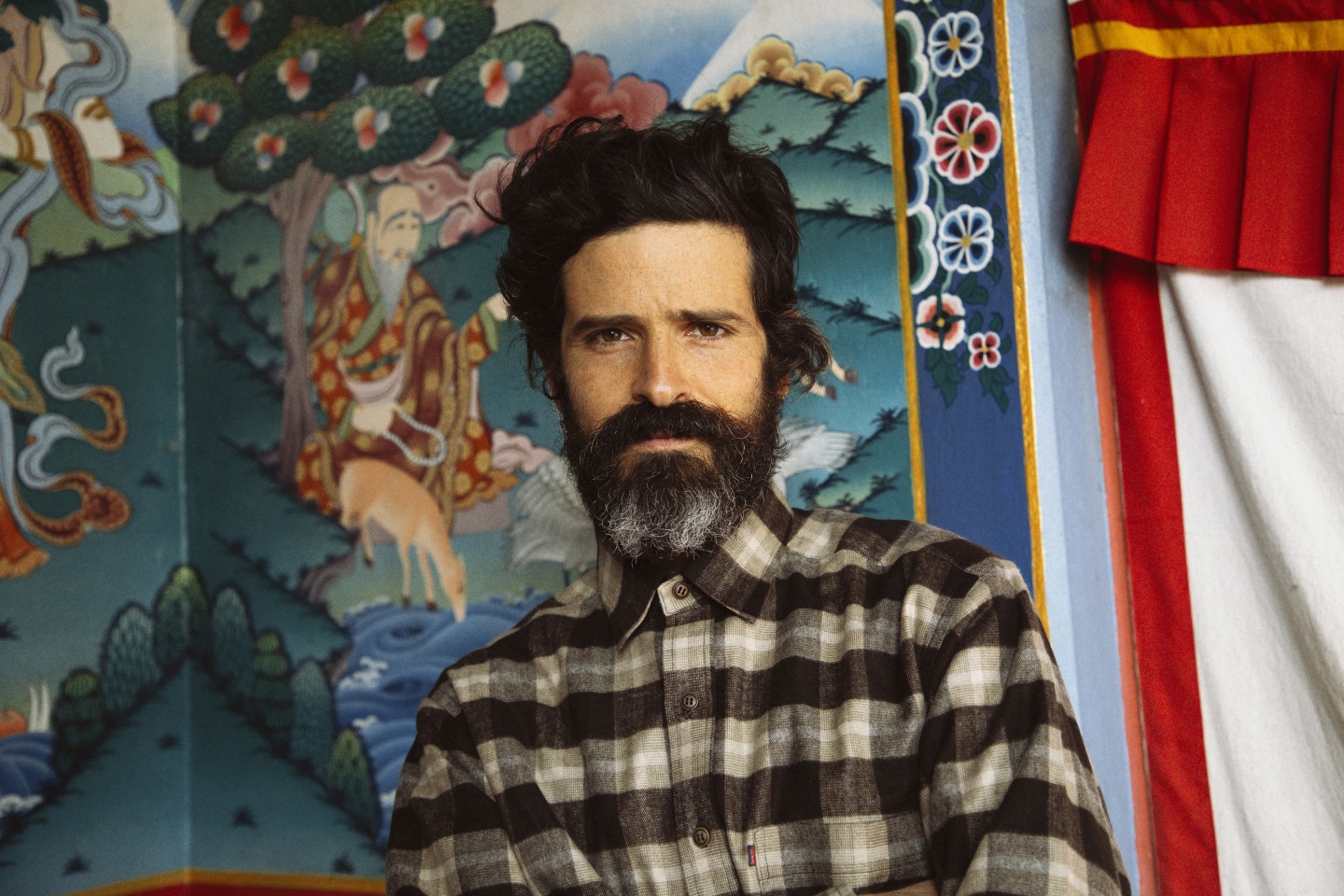

Devendra Banhart’s tenth album in nearly 20 years, Ma, is small and gorgeous — an understated and folk-leaning meditation on parenthood, loss, and family that recalls Songs of Love and Hate-era Leonard Cohen as much as it does his early classic records like 2004’s double-stunner Rejoicing in the Hands and Nino Rojo. Play it in quiet enough of an environment, and it feels like his guitar is whispering in your ear, as he switches between English and Spanish in his instantly recognizable soft singing voice.

Similar to 2016’s indelible Ape in Pink Marble, Ma is compact in its prettiness — and our conversation the day before the album’s release earlier this month was anything but. As we sat down at Cha-An Teahouse in the East Village, Banhart recalls the “many, many bad dates,” he’s had just feet from the private space we’re sitting in. (Always a globe-trotter and once a NYC denizen, he’s lived in Los Angeles for the last four years.) Over an hour-long conversation that spanned the personal and the cosmic, the two of us barely got to touch on the album itself as we mused on life and its endless machinations.

An inquisitive and funny conversationalist, Banhart gives back as much as he gets when it comes to being interviewed, and as someone who interviews people for a living, our chat was a nice change of pace. Sure, sometimes you want to hear about how the artist’s latest record was made, or what the thematic intent was behind it; but sometimes, you want to just sit down with a pot of tea and talk about the pain and pleasure of being alive.

Yesterday was 9/11. What’s your memory of that day?

My girlfriend was flying. Her flight had to be grounded in Iowa or something. I don’t think I had a cell phone, but I eventually got a hold of her. Then I just watched the footage over and over again — of course, it was on every channel. Waiting to get in touch with my girlfriend was horrifying, but that fear was numbed by the overall shock, and this tsunami of foreboding doom. It felt so global. I never felt so connected to global, foreboding doom. On that day, it really felt like the world changed for the worse.

Do you think the world ever got better?

It’s possible! We became more aware of the other side of the story. But I’m not sure if we got better. That’s one of the things that I found so amazing about Ramy Youssef’s HBO special Feelings. He makes an amazing joke that relates to that question. But, no, of course the world didn’t become better after that. The United States possibly became more conscious of its own behavior. It’s possible that people lived in the bubble that the United States is a perfect country — the Mother Teresa to the world. So it brought a new conscious that maybe that’s not the case. That’s one side of it. The other side, of course, is we became extremely — and probably more — racist. More defensive and frank.

Something I practice everyday is Tonglin. It’s Tibetan for taking and receiving. Every time there’s a horrible disaster — and there’s one daily — you breathe in all of the confusion, suffering, and pain that the individual or group of people experienced at that moment. You visualize yourself sucking in all of their pain and suffering, and you visualize breathing out healing, wisdom, and love, sending it out into the world. Does it affect those people in any way? Probably not, but it’s a tool that you can use yourself, and in terms of things that you’re putting out into the world, there are worse things.

Where are you spiritually at the moment?

Delusional, and a terrible lay practitioner — in other words, a very bad Buddhist. I practice Rasayana Buddhism. What about you?

I feel like I’m just trying to exist. As I get older I’m trying to increase my capacity for empathy to the people around me, and be conscious about the space I occupy and how it affects others around me. I guess that’s the closest I get to spirituality.

That’s beautiful. It doesn’t need to go any further than just trying to be conscious outside of yourself — of a realm outside of yourself. Other people don’t think that way, and the world does not behave in the way you want it to. You can struggle with that your entire life, and it only gets magnified the older you get — or, you accept and understand that everybody is on their own trip and has their own consciousness. But at the same time, you’re searching for that common ground, and that’s why meditation is helpful. It strips away a lot of these layers of our identity.

“This is me, this is what I’m into” — that falls away over time, and then you find something that you have in common with other people.

It’s hard not to feel angry these days. Do you feel similar?

I subscribe to two Buddhist publications. One’s called Tricycle, the other one is called Lion’s Roar. The cover of the latest issue of Tricycle is a picture of someone trying to meditate on fire, and it says “Anger.” My girlfriend saw it and was like, “Is this a feature about some place [pronounces anger as an-jer]? I’ve never heard of it!” Then she realized what she was saying and started laughing. Perspective is so funny. The next time I start to get angry, I’m going to say, “Why don’t I just go to [pronounces anger as an-jer] instead? It’s a nicer place.”

If I tweeted “I just want everyone to be happy,” somebody would write back, “Fuck you. How dare you.” No matter how at peace with other people I try to be, someone’s gonna fucking come in and just say “fuck you” to me. You accept that that’s going to happen, and once you’ve accepted that, you have to deal with the fact that you’re gonna say “Fuck you” to yourself. As good as you’re feeling, it’s gonna creep in there.

What’s your level of interaction with social media these days?

Well, I have Instagram. I don’t know who doesn’t have Instagram. There’s a lens where social media is the most vile, horrific, evil thing on Earth, and then there’s the lens where it’s creating a community for people that don’t have one. It’s connecting the exploited and disenfranchised, creating tremendous compassion and empathy. It’s just a tool! And it can be used for good or bad. I just watched a documentary about what’s it like to be a teen in high school with Instagram. There’s a moment where a kid posts a photo, and then they take a screenshot and they delete it — and then they look at the screenshot to see how that photo worked with the other photo. I look at it through a lens that’s like, “Wow, you’re putting a lot of work into this, I appreciate that!” But that’s me trying to find something positive in it. Mostly, the necrosis is at such a high level, it’s insane.

I’m hypocritical, because I think it’s so cool that it can be a glimpse into somebody’s life whose work I really admire. I love Meredith Monk, and with Instagram, I get a chance to see if she has a cat, and what’s she reading. I just want to be creepy and see what her kitchen has. I love it when people get really personal and a friend posts something that’s just like, “I’m going through some shit and I just wanted to get it out there.” There’s something so beautiful about that. I’d like to use it more like that, but I don’t know if I’m intimate enough. I just post about shit that I care about, that’s about it. Maybe I should be funny with it, too — like, the next time I go to get a colonic! [Laughs] Because I love colonics, and I don’t get enough of them. It’s been a long time.

When’s the last time you had one?

Way too long! Maybe a year or so, even more. I’m embarrassed to say that, because I think of myself as like a real colonics expert. The truth is, it’s just enemas these days. They’re easier to get. But I should invest in a beautiful colonics machine — the Tesla of colonics machines. I’ve always wanted to invent something called the septiside: a little tube that goes into each orifice, and you turn it on and it sucks it all out. Doesn’t that sound wonderful? That’s a very Western perspective. I just want it all gone with the press of a button.

When’s the last time you felt pain?

Today. I talked about Venezuela in an interview and it made me immediately want to cry. Then I thought about Daniel Johnston. That made me want to cry. His art was so beautiful. How about you?

Today. My cat got really sick like two months ago, and I was away doing a story while my wife was taking care of her. The story was published today and I was revisiting the experience in my mind, it still feels very fresh. Pain is instructive.

It certainly is, but how quickly do you forget? You’re thinking about the memory of pain. You can almost relive it, but it’s not the same. Pain changes, obviously, but the memory remains and changes as well. Often, when you look back, you go, “I suppose it’s psychological pain.” Was there any point of having that pain? You could’ve spared yourself a lot of physical anxiety and pain if you had just looked at the situation, which is this: If there is a solution, then you shouldn't feel any sadness. Assume it’s gonna work out and there’s gonna be no pain, and if there’s no solution, there’s truly nothing you can do. Why burden yourself with this extra pain?

But the mind it doesn’t work that way, except for people who have meditated for, like, fifty years.

The rest of us are just stuck with this suffering, and it’s even crazier when the memory of the pain is just as real, or stronger, because it’s grown over time. It’s really frightening.

As you get older, is your memory sharper?

As I get older, I’m a new old person in a new country called “being old.” I’ve just arrived, I’ve got my Hawaiian shirt on, I’ve got my camera — let’s check it out! I haven’t found that I’m duller or sharper due to age. I’m sharper when do everything I don’t want to do for up to ten days. For some people, that can be called a retreat. Focusing on practice. not texting so much, being conscious of what goes into my body, doing a little bit of exercise and loving myself, not paying so much attention to those thoughts that come in and say, “You’re a total piece of shit.” It ebbs and flows, but it feels like it’s forever while it’s happening.

Your music has become more miniature over the years.

I’ve got a friend who’s friends with David Lynch. She was having dinner with David and his wife, and they were having an argument, and he said, “Don’t you understand, I just want a room with nothing a hole with some oil in it — that’s it.” Then he cracked up. But when she told me that story, I thought, “Oh fuck, I can really relate to that.” I just want a room with a hole in it. I don’t know about oil — maybe I’ll take some chamomile tea. I’d like just a room, with a hole, some chamomile tea, and maybe a little bit of moss in the corner and a tiny watering kit.

In a way, when you’re first starting out making music, you want to show people that you can do stuff. At the beginning, I just had a four-track and a guitar Then, suddenly, you have access to more stuff, and you go nuts. But that’s not what I’m interested in. I’d rather have nothing in my house. Maybe the only place you can do that is with music.

In the press materials, you talk about childlessness and whether or not you’ll ever become a father. How do you feel about that notion right now?

Well, buy me a drink and see where this goes. [Laughs] I suppose it doesn’t really matter if I have a kid or not. And if it matters, then I’ll deal with it in whatever way and I’ll suffer. [Laughs] Maybe I’ll make a record about the suffering of not having a child. Or, I’ll accept it, and it’s fine. This record isn’t about if I have a child or not — it’s really about reaching that point where I’m this new old person. It seems pathetically optimistic, but it feels like I’m landing in this new place.

My world is suddenly filled with these little kids, because these people that I’ve been in a band with since we were little kids now have children. Not only did I have this incredible opportunity of not having a child and therefore being able to observe that relationship between them and their children, but I can go home and write about it. That’s something they don’t have the luxury to do. Of course, you can write amazing art while you have children, but I have an extra luxury.

Listen to Devendra Banhart's Ma album: