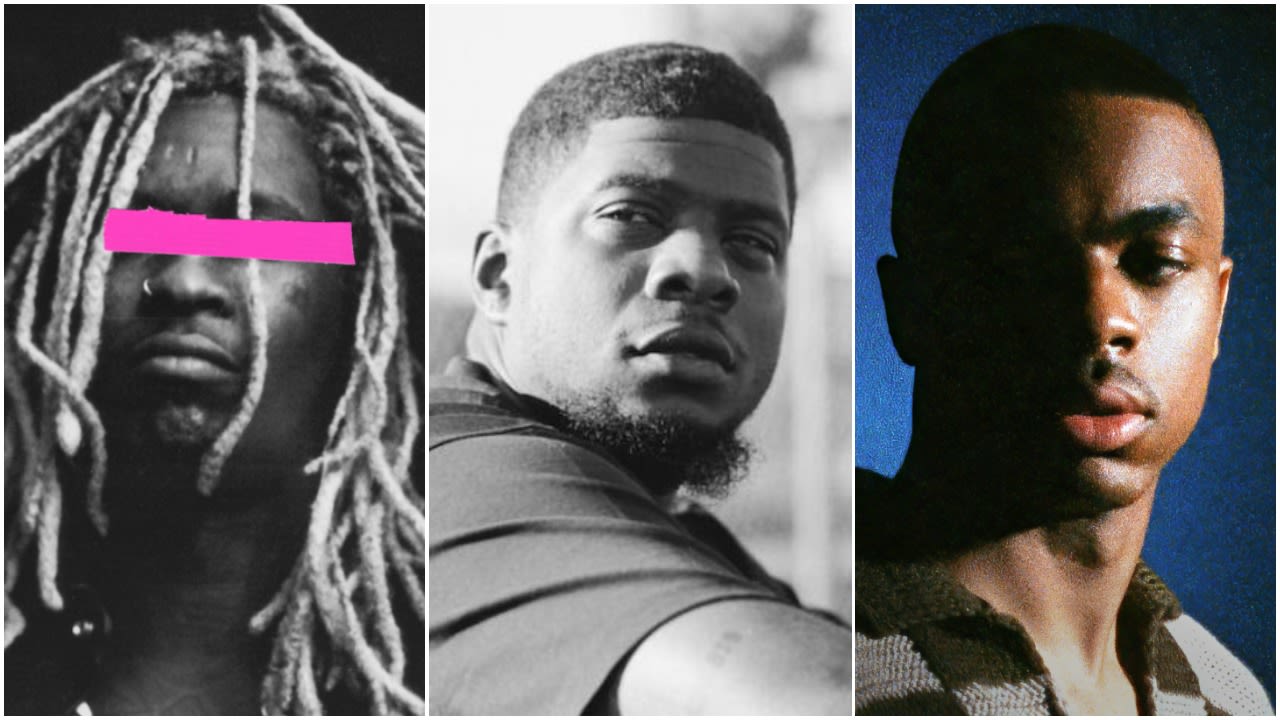

(L) Photo by Josiah Rundles (M) Photo by Brian Lamb (R) Photo by Zamar Valdez

(L) Photo by Josiah Rundles (M) Photo by Brian Lamb (R) Photo by Zamar Valdez

In advance of So Much Fun’s release, Young Thug talked about his plans to release another album in a few weeks. It would be titled Punk. “[Punk] means brave, not self centered, conscious. Very, very neglected, very misunderstood. Very patient, very authentic,” the Atlanta rapper said, further describing it as “music that the world is going to embrace.” The first half of the promise would be broken—at this point in Thug’s career, no one should have been heartbroken by that—but the latter half remains true. When Thug previewed a few of the songs that would become Punk this summer, it was clear the “embrace” he yearned for wasn’t a manifestation of commercial success. Instead, Young Thug wanted to be sure that he was heard.

Recalling the acoustic warmth of 2017’s Beautiful Thugger Girls, Punk reshuffles Thug’s artistic priorities. Sprawling, detailed free-wheeling monologues bleed into some of his tightest and heartfelt songs in years. While there are still attempts at finding a song that fits perfectly into the rap-as-wallpaper aesthetic of RapCaviar (“Livin It Up,” “Bubbly”), it doesn’t particularly feel right to pick the album apart for singular tracks—it feels more apt to listen to short stretches or even allowing the sprawling album to play out in full to let it all wash over you at once.

In that way, Punk mainly operates in a different space than pain music, the melodic and bluesy stain of rap that’s come to dominate rap. An entire cottage economy of type beats featuring dour guitars and somber piano melodies popped up in response to the rise of Polo G, YoungBoy NeverBrokeAgain, and Rod Wave. Certain cuts from Punk and Polo’s Hall of Fame likely wouldn’t feel too out of place next to each other on a playlist, but it doesn’t feel right to place these in the same sort of lineage. The slight difference in their approach makes all the difference— The Rod Waves of the world cry outwardly in hopes that their music finds someone who shares their burden, an inversion of the kind of digital closeness that Punk strives for.

This year in rap, Thug isn’t alone in making music that, while somewhat muted, maintains the intimacy of a late-night heart-to-heart on the porch. Albums from eccentric stylists like Sahbabii and Thugger and ambitious concept-driven artists Mick Jenkins and Vince Staples share an affecting directness that’s impossible to look past. These albums function as a release of emotions that have been brewing for years or were spurred by recent tragedies. They’re rapping with their inside voices—loud enough to be understood, but quiet enough to not draw unwanted attention. By stripping down their songwriting to its rawest form, they’ve each come with projects that stand out in their respective catalogs as hazy journeys in search of clarity.

Vince Staples has spent the year in interviews speaking about how he creates without accounting for fan expectations. “I don’t really try to tell anyone what to do, or how to receive what I say or what I do,” he told NME. Like the buzzing, fluorescent lights of a hospital waiting area, his bleak self-titled album stretches 22 minutes into eternity. Vince’s reluctance to explain his work is understandable. Vince Staples is clouded by ennui and its low-energy emotional range—the irritated “ARE YOU WITH THAT?,” and anxiety-laden “SUNDOWN TOWN” come to mind first—doesn’t inspire short-lived action as much as it does rumination on the source of those listless emotions. Gravestones and eviction notices are recurring images in Vince’s music, but they sting a little harder when plastered onto Kenny Beats’ grayscale production. When you’ve seen as much loss and violence as Vince has and have spoken about it for years, what good does exerting more energy than necessary do when folks haven’t been paying attention?

On Elephant in the Room, Mick Jenkins borrows a bit of Vince’s candidness. The Chicago MC made a name for himself in the mid-2010s with tightly-composed mixtapes that demonstrated a love of poetry and wide-scoped narratives. Elephant in the Room doesn’t attempt to match the thematic cohesion of The Water(S) or see Jenkins don his best Gil Scott-Heron impression for a skit, but it maintains him as an ever-effective storyteller. His writing, more lucid and than ever, explores love, the tension it comes with, and fatherhood. “We only talk ball,” Jenkins grits through his teeth on “Reflection.” “We only talk once a year, not even that, I don’t call. I haven’t called in like three.” The mundane images he conjures—the height difference between him and his father, the lip gloss his wife uses—are intertwined with slick wordplay and extended metaphors.

His use of simplistic detail makes me think of fellow Chicago rapper Polo G, whose vivid imagery builds relationships between the people he raps about and the world that surrounds them. Blocks attached to memories of days playing outside become memorials and all the funeral pamphlets and eulogies he’s seen begin to blend together. This is the core of all pain music—there aren’t singular moments of distress. The haunting recurring images they rap about become generalized to the point where they’re damn near numb to it all. When Young Thug’s howls are drenched in Auto-Tune, Vince Staples’ shrugs through his paranoia, or even when Mick Jenkins observes his life in meticulous detail, they don’t ring out with the same intensity; they flash across the sky for a brief moment before burning up like an asteroid. If you manage to catch a glimpse, it’ll stick with you forever.