HBO

HBO

The Idol writer and director Sam Levinson is no stranger to backlash and controversy. As the creator of Euphoria he has been repeatedly accused by critics of over-sexualizing the splashy Emmy-winning teen drama’s female characters, with actors on the show speaking about his limited view of certain characters. He doesn’t seem to take criticism too well, either. His truly terrible 2021 movie Malcolm & Marie is billed as a relationship two-hander starring Zendaya and John David Washington but acts largely as a vessel through which Levinson can complain about movie critics (especially those who didn’t like his previous film, Assassination Nation).

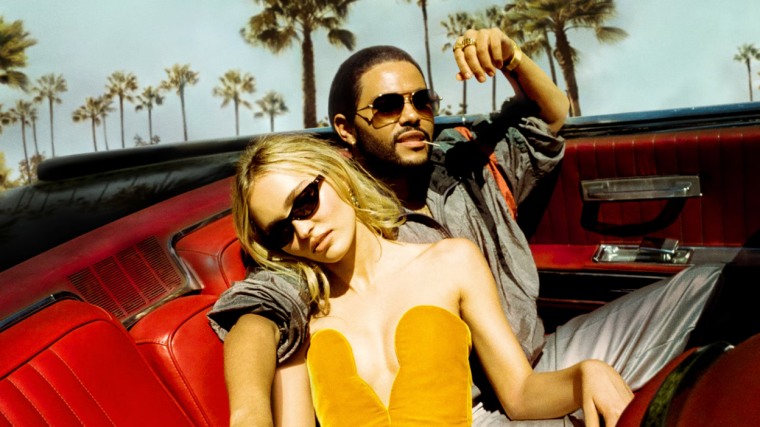

You have to wonder, then, how he is feeling about the initial response to The Idol, his new series co-created with Abel “The Weeknd” Tesfaye. The series premiered at Cannes, a nod to its European arthouse ambitions, but was largely panned. On the eve of the first episode debuting on HBO, the show has a 25% score on Rotten Tomatoes.

Much of the criticism out of Cannes was that The Idol is explicit and misogynistic in its depiction of a young pop star and the seedy nightclub owner she becomes involved with. The accusation isn’t helped by reports that The Idol’s filming was toxic, with director Amy Seimetz fired from the project amid concerns from Tesfaye that she was making a show with too much of a female perspective. Levinson responded by stating: “Sometimes things that might be revolutionary are taken too far.”

In a neat piece of meta-context for the viewer, this idea of an industry of sharks and bullshitters foisting their agendas on a female artist (Lily-Rose Depp) lies at the heart of The Idol. Depp, for her part, plays Jocelyn with an effective blankness. She is presented as a music industry pawn, one who is lauded as a genius by her manager Chaim (Hank Azaria) but who hates her own music and is largely going through the motions. The opening photo shoot does reveal one key ability, though: she is fully in control of her emotions and able to use them to her advantage. When a photographer asks, she cries on cue. A fake tear rolls down her cheek as if to remind you that how she looks and how she feels might not always be in alignment.

When it is in industry parody mode, The Idol is amusing and sharp. A photo shoot for the mononymous Jocelyn’s album cover provides space to fire shots at the role of intimacy coordinators ( or “nipple police”), nudity riders, and people who spend too much time on the internet. It’s not just generation-gap sexual politics, though. There is a keen awareness that everyone here knows their role is as flimsy and unnecessary as they view the intimacy coordinator to be. The pop star “team,” a coterie of people taking their jobs far too seriously, is sent up nicely. This is a world filled with everyone having somebody breathing down their neck and being one wrong move from the exit. By extension, The Idol’s world is one where everyone, from lowly assistants to powerful agents, is only ever looking out for themselves.

Autonomy is debated throughout The Idol. “It’s my boob and my house,” Jocelyn says at one point as she pushes for more nudity on her album cover. There’s talk of a psychotic break she experienced that is hushed in real-time by other members of the team. In one scene her publicist (Dan Levy) and a visiting Vanity Fair writer (Hari Nef) compare Jocelyn to Britney Spears, perhaps the ultimate example of a pop star who had her freedom taken from her. It feels like The Idol wants to have it both ways, though, decrying exploitation in the pop world while also poking fun at efforts to correct that system. The music world can be a hypocritical place but by taking both stances, The Idol comes out with no discernible viewpoint at all.

It’s not the critiques of the music world that let the show down, however. This is a show that flaunts its explicit nature like a teenager bringing an R-rated movie to a sleepover. Tesfaye’s music has never been subtle in relation to sex and that runs through into his debut TV venture. Much of the drama of the opening episode revolves around a photo of Jocelyn with ejaculate on her face that has leaked online. The scurrying members of her team are doing all they can to put the fire out but eventually, she sees that an intimate moment has become a trending topic. Her reaction is deliberately hard to read. “It could be a lot worse,” she says as she makes a quick exit. The leaked photo, which of course is shown, leads to a strained debate on the definition of “bukkake.”

Such scenes, which also include Depp’s character dancing in a tiny bikini and engaging in auto-erotic asphyxiation demonstrate Levinson’s tenuous grasp on provocation, The Idol’s stated raison d'être, The idea that the nudity and sexual nature of modern TV and movies, of which there is increasingly little, exists only to titillate the viewer and reflect that tastes of the (male) director is simplistic and ahistorical. Far from the second coming of Paul Verhoven, whose Basic Instinct makes a brief, almost self-defensive cameo in episode one, Levinson and his style display rudimentary urges that a smarter creative team would resist. The Idol seems to revel in its depiction of sex, though, like that same horny kid pointing at the screen to show his friends what is happening.

Jocelyn’s search for autonomy draws her closer to Tedros, a sleazy nightclub owner played by Tesfaye. Entering his world feels like an escape to her but it would appear to be more like a trap door. “When you’re famous everyone lies to you,” she tells him at one point. “I think you’re enough of an asshole that you might tell me the truth.” It would have been kind of someone involved in The Idol to tell Tesfaye the truth about his own acting abilities, which appear lacking in this opening episode.

It’s hard to not think about The Weeknd’s own emergence into the music industry and how he used anonymity and withdrawal to maintain his own autonomy. In his early career, people barely knew what he looked like and that was part of the appeal. In The Idol we have seen Jocelyn’s revenge porn within half an hour. Perhaps this is a comment on the sexualized nature of the female pop star and the hypocrisy of the post-woke world in which she operates. Or perhaps, like much of The Idol’s intriguing yet indulgent and contradictory opening episode, it’s just not that deep.