Courtesy the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Courtesy the Cincinnati Art Museum.

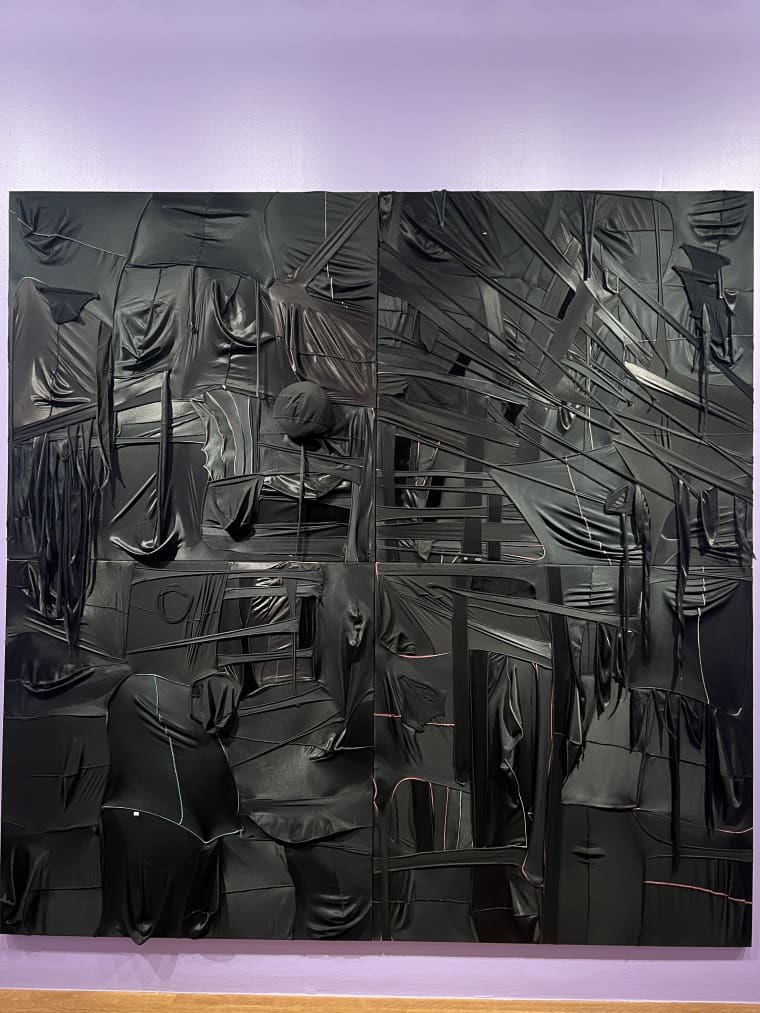

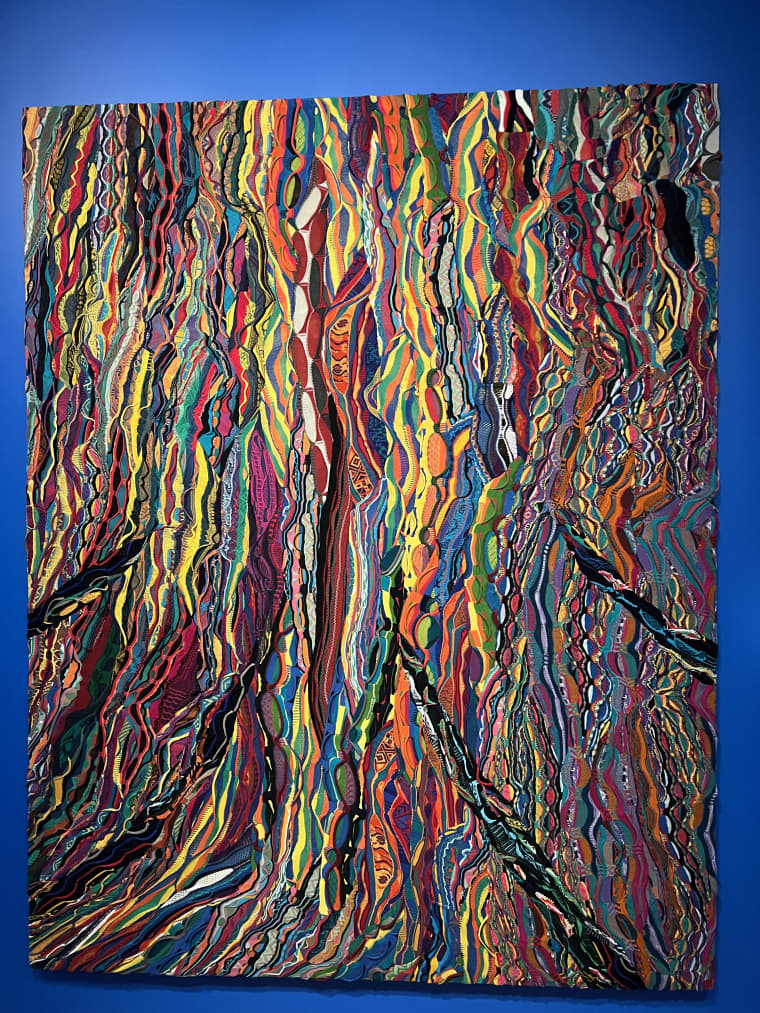

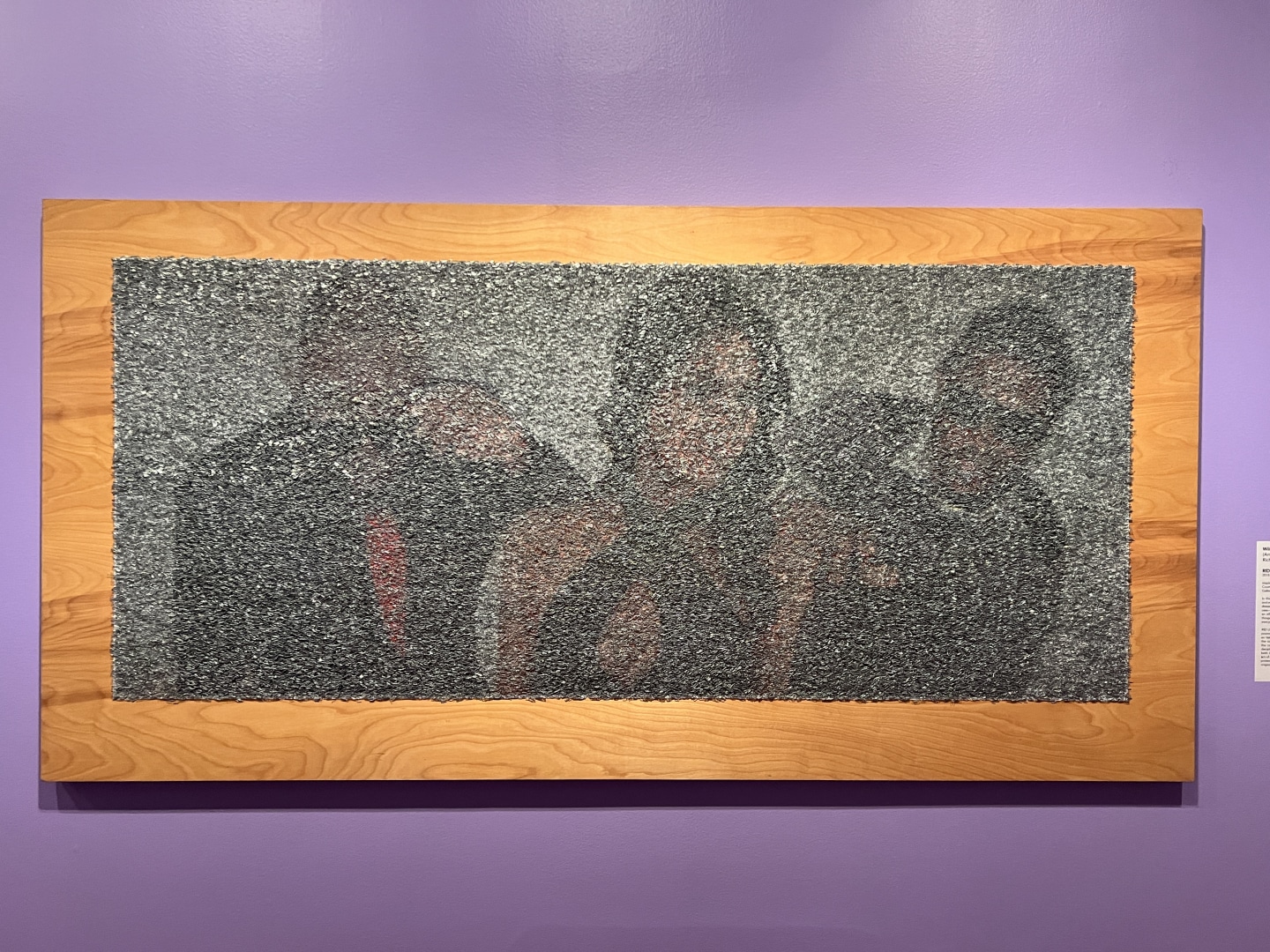

Traipsing through The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century, on display at the Cincinnati Art Museum through September 29, 2024, I felt desperate to press my fingers against piece after piece, consequences be damned. There was the mercerized cotton of Jayson Musson’s “Knowledge of God,” a rainbow weave that seemed to thread Coogi sweater flexes to dreamcoats of Biblical yore, and the inky elastic durags of “CAMOUFLAGE #105 (Metropolis)” by Anthony Olubumni Akinbola, museum lights glinting off its surface like sun on waves. These works may have been static, but certainly not inert, eagerly reacting to viewers: the metallic forcefield of staples shrouding Wilmer Wilson IV’s “RID UM” shimmered with prickly energy, offering a slightly different experience from each angle, while the lightweight silk of “Ascent” by John Edmonds wriggled under the slightest breath.

"CAMOUFLAGE #105 (Metropolis)" (2022) by Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola. Photo by Vivian Medithi.

"CAMOUFLAGE #105 (Metropolis)" (2022) by Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola. Photo by Vivian Medithi.

"Knowledge of God" (2015) by Jayson Musson. Photo by Vivian Medithi.

"Knowledge of God" (2015) by Jayson Musson. Photo by Vivian Medithi.

The tactile allure of these artworks mirrors the “graspable language” underpinning the exhibit, which highlights the surprisingly wide middle ground between the seemingly disparate realms of “high brow” visual art and “low brow” rap music. Initially conceived as a collaboration between the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Saint Louis Art Museum as a celebration of hip-hop’s 50th anniversary, The Culture side steps grand, definitive statements about where hip-hop has been or is going. Instead, the exhibit seems content to start an open-ended conversation — the specific conclusions audiences draw are less important than the simple fact of their reaction to the work in the first place.

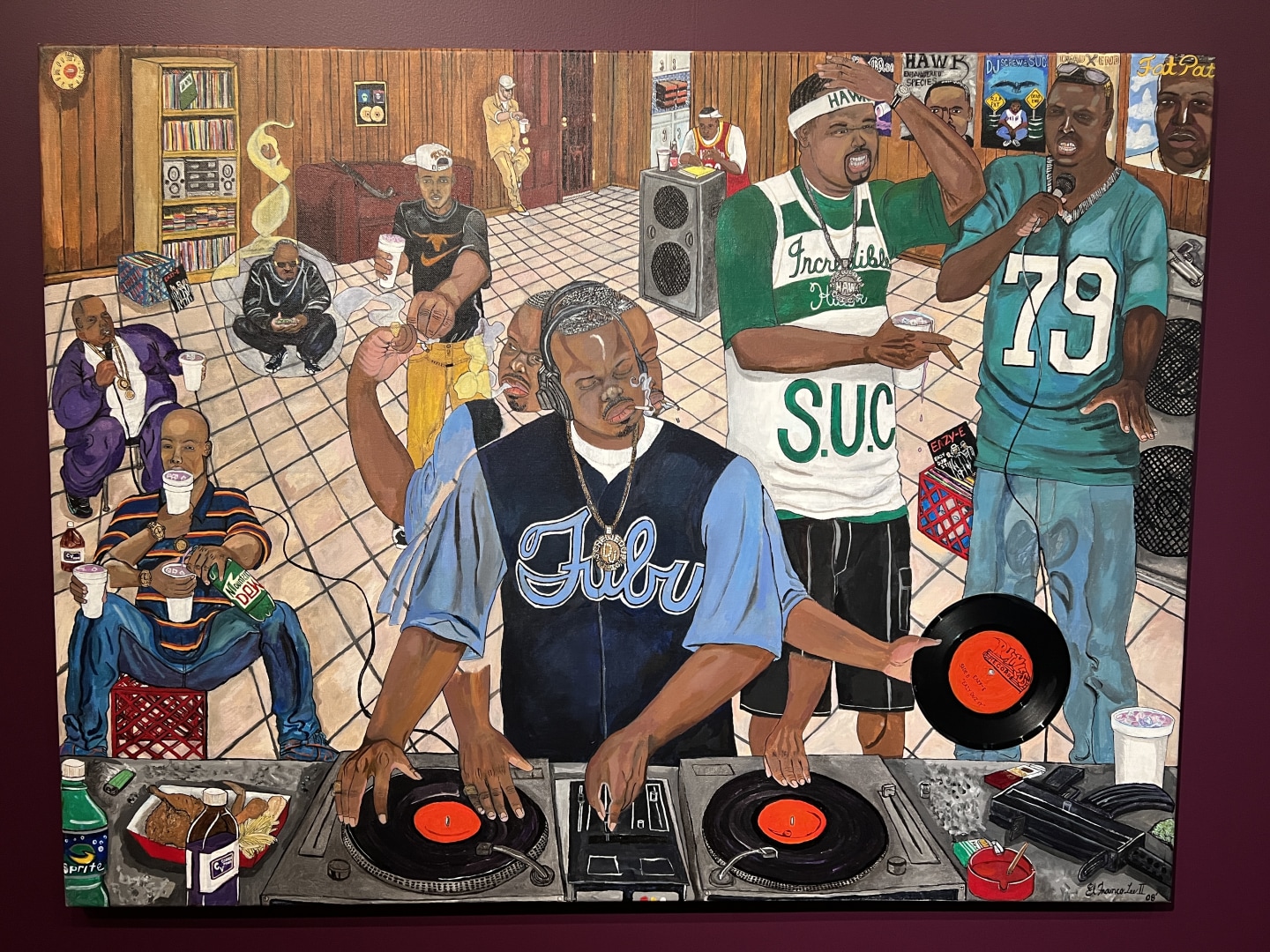

An exhibit of this sort is doomed from the outset to serve as a partial survey of a wide-ranging field, and it’s a testament to the thoughtful and idiosyncratic curation of Professor Jason Rawls here in Ohio (as well as prior curators Asma Naeem, Gamynne Guillotte, Andréa Purnell, and Hannah Klemm) that The Culture is intimate rather than daunting, accessible rather than overwhelming. Constructing a space where Marcel Duchamp-inspired text work can converse with Lil Kim’s wigs and photography by Carrie Mae Weems, The Culture maintains an amorphous, expansive vision of hip-hop, neither prescriptive nor exclusionary. Works are loosely grouped into six categories under headings like “Language” and “Pose,” though these classifications quickly begin to bleed into each other: a leather bomber jacket from Gucci’s collaboration with Dapper Dan situated under “Brand” could have easily fit next to the Hank Willis Thomas grills under “Adornment;” a quasi-Cubist acrylic painting by El Franco Lee II honoring DJ Screw in “Tribute” could logically slot into “Ascension.”

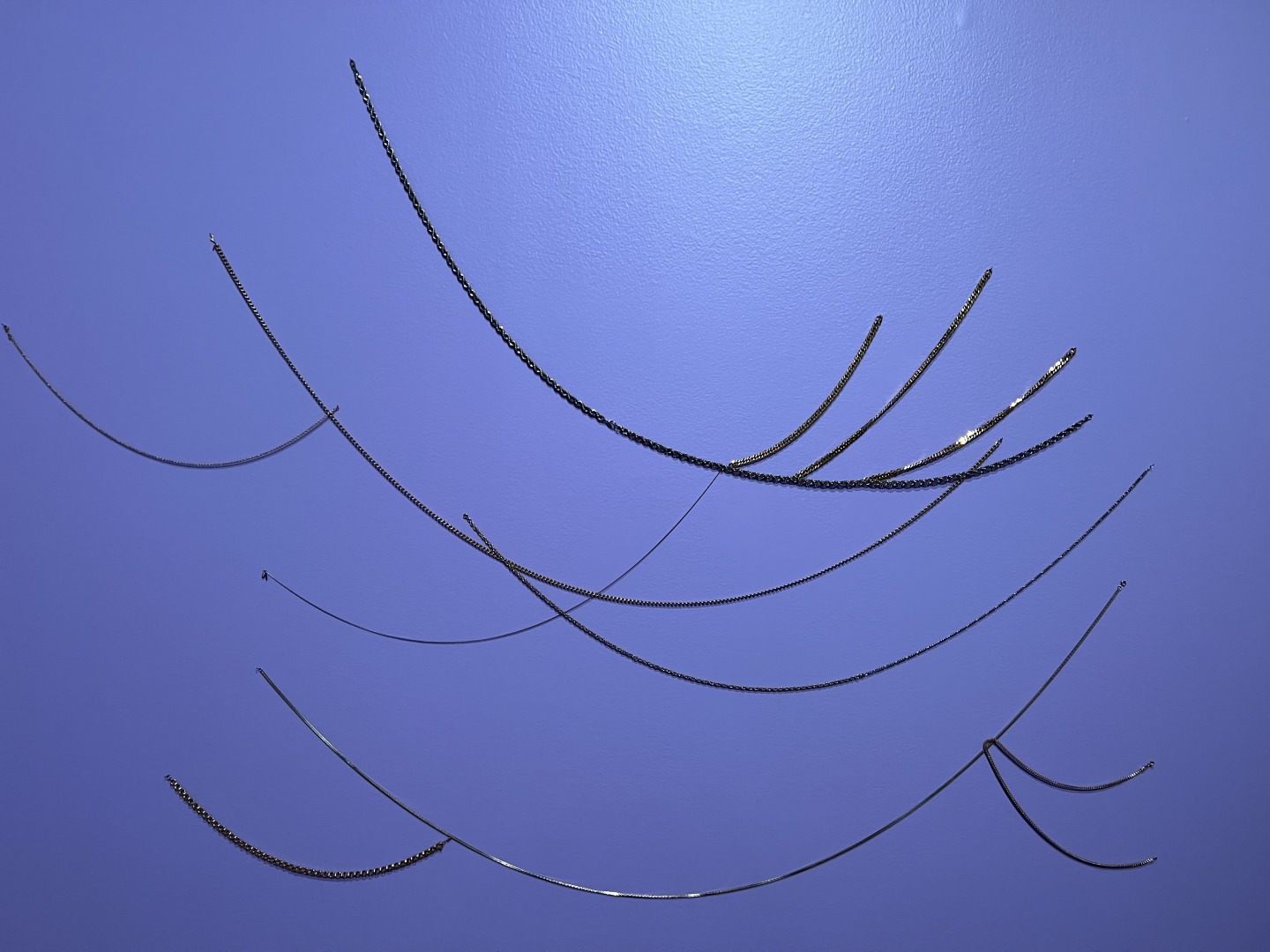

These section divisions feel more arbitrary than organizing, but The Culture nevertheless finds a comfortable flow, with larger pieces by ceramicist Roberto Lugo, painter Shinique Smith, and installation artist Lauren Halsey serving as natural rests in between the staccato rhythm of memorabilia and smaller scale artworks. It’s here that the exhibition’s weirdness really shines through, from a porcelain-and-cigarette-butt Kahlil Robert Irving sculpture grappling with police brutality to a triptych of photos by Alex de Mora tracing hip-hop’s global reach all the way to Mongolia. I was particularly taken by Robert Pruitt’s 2004 piece “For Whom the Bell Curves,” a wall sculpture of gold chains retracing the lines of the Transatlantic slave trade, which offered a particularly woozy emotional whiplash between its pleasing aesthetics and discomfiting semiotics; and by Larry W. Cook’s video piece “Picture Me Rollin’,” which sets the Big Tymers clip for “Get Your Roll On” to a chopped-and-screwed iteration of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream,” an admittedly cheesy mashup I found compelling anyways.

"For Whom the Bell Curves" (2004) by Robert Pruitt. Photo by Vivian Medithi.

"For Whom the Bell Curves" (2004) by Robert Pruitt. Photo by Vivian Medithi.

At times, The Culture highlighted the limitations of what a museum exhibition can be. The inclusion of pieces like Chance the Rapper’s overalls and Travis Scott’s Air Jordans are understandable from a marketing perspective, but their presence here makes genuinely cool tracksuits by Baby Phat and Telfar seem tacky by association. Pharrell Williams’s endlessly memed Vivienne Westwood hat is here, on loan from Arby’s; in similarly investment-savvy fashion, Williams has in turn loaned the collection a bomber jacket from his own Adidas collab, an unimpressive bit of sponcon jammed in the middle of the gallery. Commodification is part of hip-hop’s DNA, but does it have to be so gauche?

Elsewhere, an NFT by Derrick Adams paid homage to JAY-Z’s Reasonable Doubt cover, though the most interesting thing about it was that the Web3 smart contract was indistinguishable in presentation from a regular video. And laying limp against the gallery wall, Devan Shimoyama’s chain of bedazzled Timberlands felt corny rather than transcendent. The omission of Kanye West-related pieces made perfect sense given the embattled ex-superstar’s antisemitism, but his forays into apparel and creative exchanges with artists like Takashi Murakami, George Condo, and Virgil Abloh feel far more pertinent to the landscape of contemporary hip-hop than some of the work on display here.

Courtesy the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Courtesy the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Case in point: the Arthur Jafa-directed video for “4:44” by JAY-Z, which plays in a main floor gallery as a teaser to the exhibit proper. The clip finds Jafa shrinking the scope of his found footage video collage to an interpersonal, rather than institutional scale, deploying his typically jerky edit style toward catharsis for disloyal husbands. But this is a music video for the guy who once said “I’m not a businessman, I'm a business, man;” as Shawn Carter has climbed to capitalism’s upper echelons, his interest in fine art has come across like a well-funded branding exercise just as often as it has manifested genuinely intriguing work. And it’s hard to be upset this isn’t Jafa’s peak when his middling work remains choppily magnetic, deftly playing with the “gap between images,” the gestalt of their juxtaposition.

Though his practice includes sculptures and paintings, Jafa’s principle medium is video collage, assembling found footage to surprisingly disarming effect. The pacing of the Internet at large occasionally makes the juxtaposition in Jafa’s videos, which stack images of racialized policing, surveillance, and violence against memes, flexes, and interstellar imagery, feel quaint or predictable. And his work can be intentionally jarring to the point of offense, as when his 2020 video for Kanye West and Travis Scott collaboration “Wash Us in the Blood” utilized footage of Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor. But by and large, Jafa achieves a supercharged reaction thanks to his earnest desire to push audiences to confront capital letter Preconceptions about Race, both in society and in themselves.

“4:44” by JAY-Z fails to meet this lofty mark, more technically good than passionately great. In that, the video more readily recalls the clickbaity conceptual art of 2013’s “Picasso Baby” than Jafa’s video art. The quantum differential became crystal clear when I stumbled into a collection of Jafa’s work at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago a month later. Unconcerned with digestibility or approachability, these pieces cheerfully pushed viewers’ buttons at warp-speed, clobbering audiences with a deluge of images and sounds. Despite the visual bludgeoning, clips invariably stick in your memory: for weeks, I’ve been reminiscing on an excerpt of “The White Album” in my head, a group of cybergoths dancing under a bridge to “Mask Off” by Future and Metro Boomin. In a way, this sort of information overload, constructed around a mountain of recontextualized samples, feels more honest and representative of hip-hop than any neatly arranged gallery catalog could ever hope to be.

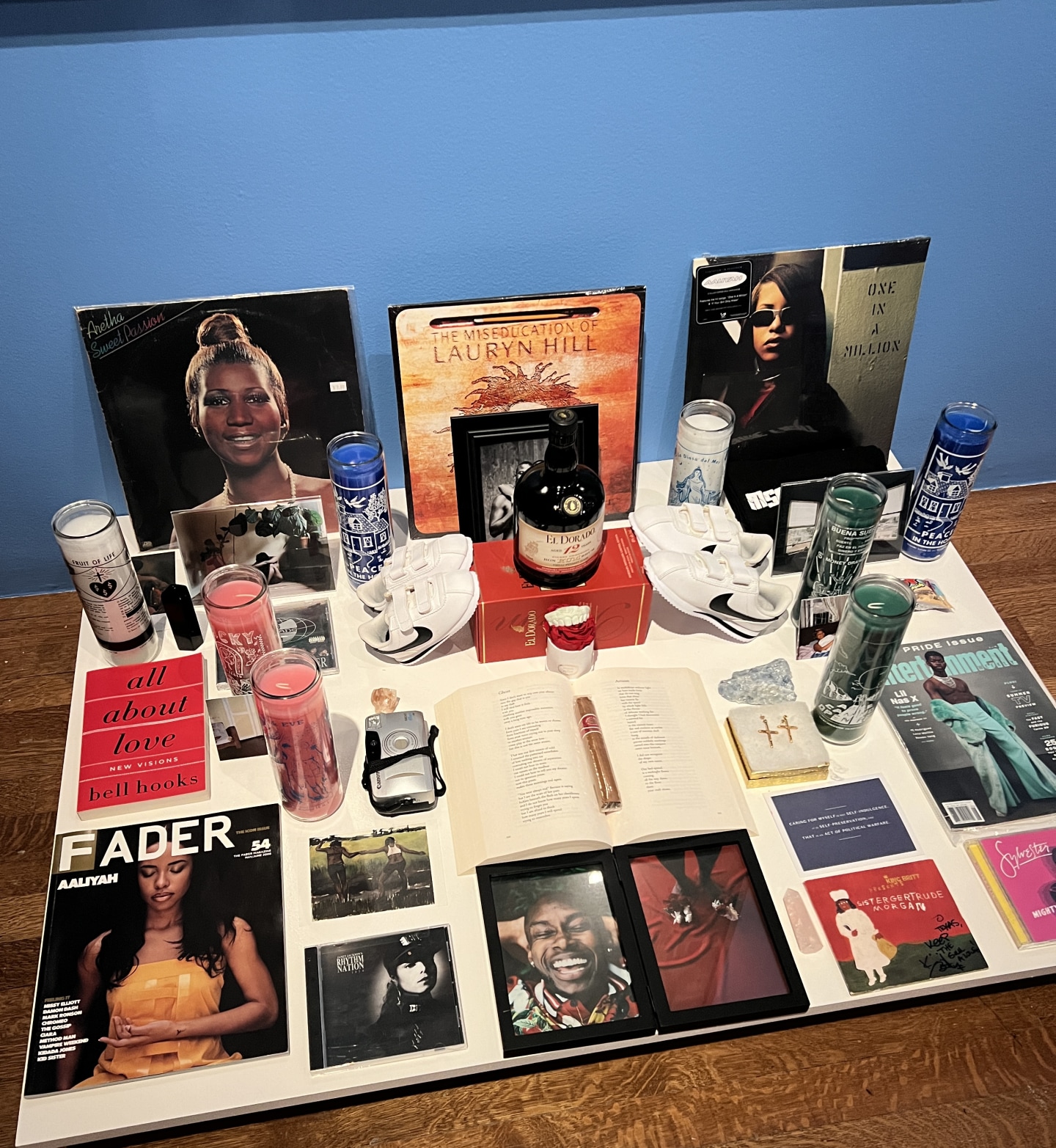

Nevertheless The Culture feels fresh and fairly plugged in, even if you get the sense a 2slimey song would leave the curators with a ringing headache. An altar by Texas Isaiah placed a 2008 issue of The FADER featuring Aaliyah on the cover amidst items including a copy of bell hooks’s all about love, a CD of Rhythm Nation by Janet Jackson, prayer candles, a plastic wrapped cigar, and a magazine featuring Lil Nas X; at the exhibit’s close, a Caitlin Cherry oil painting “Bruja Cybernetica” stacks Getty Images shots of City Girls and Bia against screenshots of TikToks and memes, soaking the collage in psychedelic color. An untitled Nina Chanel Abney piece recreated the collage artist’s cover for Meek Mill’s 2021 album Expensive Pain on a background of pink rather than blue, transfixing this writer time and again, while a pair of enormous Nike Air Force 1’s, constructed out of car parts by Aaron Fowler in 2022, seemed to mimic the shoes’ outsize presence in American life near the museum’s entrance.

"RID UM" (2018) by Wilmer Wilson IV. Photo by Vivian Medithi.

"RID UM" (2018) by Wilmer Wilson IV. Photo by Vivian Medithi.

One of my favorite corners of the exhibit found a vivid Lambda print portrait by Hassan Hajjaj titled “Cardi B Unity” positioned near a Cross Colours bucket hat the rapper wore at the 2018 Grammys and a minimalist wooden sculpture by Tariku Shiferaw entitled “Money (Cardi B).” Toggling between lowbrow and highbrow, the dialogue between these pieces was left up to interpretation, unmediated by gallery labels. The audience was left to bounce between concrete representation and abstracted homage on their own, connecting the dots from start to finish the best they can. In that sense, The Culture feels a bit like the beat on a cypher, an insistent backing track waiting for individuals to make it their own.

"DJ Screw in Heaven" (2008) by El Franco Lee II. Photo by VIvian Medithi

"DJ Screw in Heaven" (2008) by El Franco Lee II. Photo by VIvian Medithi

"Untitled" (2023) by Texas Isaiah. Photo by Vivian Medithi.

"Untitled" (2023) by Texas Isaiah. Photo by Vivian Medithi.