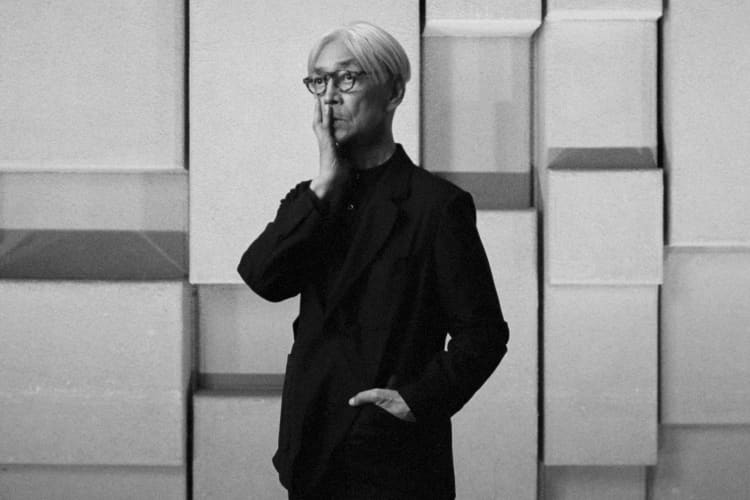

It’s hard to overstate the significance of the Ryuichi Sakamoto singularity. His half-century career spanned from Tokyo to New York City, both stylistically and physically, and his influence was stratospheric.

In the ’70s, Sakamoto drafted the founding documents of city pop with Haruomi Hosono and Yukihiro Takahashi as Yellow Magic Orchestra. In the ’80s, he came into his own as a solo artist and a prolific scorer of everything from iconic feature films to iconic whiskey commercials. Not to mention his 1980 track “Riot in Lagos,” which prefigured the next 20 years of dance music.

The ’90s saw Sakamoto expand in all directions, working with artists on the bleeding edge of experimentalism while simultaneously returning to his roots as a pianist. And the first decade-plus of the 21st century found him making forays into ambient, bossa nova, and pure pop.

The final decade of Sakamoto’s life began with an oropharyngeal cancer diagnosis in the summer of 2014. He dealt with his disease with supreme dignity, his already-unmatched grace growing even more pronounced. The two albums he released between his diagnosis and his death last year contain some of his most gutting music. From the first brutally bare chords of async’s opener “andata” to the plinking, atonal finale of 12, his reckonings with mortality were deeply introspective and unflinching.

Earlier this year, we received Sakamoto’s final masterwork — a film documenting live, solo piano performances of 17 songs he handpicked from his enormous catalog, as well as three previously unreleased pieces. The project, aptly titled Opus, was directed by Neo Sora and shot with a crew of nearly 30 over the course of several days, not including weeks of pre-production. In a written statement, Sakamoto recalls the time spent meticulously storyboarding the shots, drafting the film’s hyper-specific details through rehearsal sessions recorded on an iPhone in Sakamoto’s home. According to Sakamoto, Sora’s exhaustive process was “so that the camera positions and the lighting changed significantly with each song.

“…I went into the shoot a little nervous, thinking this might be my last chance to share my performance with everyone in this way,” he goes on:

We recorded a few songs a day with a lot of care. I played some pieces that I had never played as solo piano performances, such as “The Wuthering Heights” (1992) and “Ichimei - Small Happiness” (2011). I played “Tong Poo” in a new arrangement at a slower tempo than I’ve ever performed it. So, in some sense, while thinking of this as my last opportunity to perform, I also felt that I was able to break new grounds. Simply playing a few songs a day with a lot of concentration was all I could muster at this point in my life. Perhaps due to the exertion, I felt utterly hollow afterwards, and my condition worsened for about a month. Even so, I feel relieved that I was able to record before my death — a performance that I was satisfied with.

An album version of the film arrives today, and Jordan and I took the opportunity to go through Opus track by track, using each individual cut as a keyhole-sized window into Sakamoto’s cavernous, kaleidoscopic career. — Raphael Helfand

1. Lack of Love

The 2000 Sega Dreamcast video game Lack of Love feels like it was designed explicitly for a Ryuichi Sakamoto soundtrack. Players take on the role of a simple alien creature on a terraforming planet who must interact with the native life to survive and evolve; how one does that, violently or otherwise, is up to the player. “Lack of Love” captures the stakes of such a concept with operatic flare in a sparse package. — Jordan Darville

2. BB

The first of three original tracks on Opus, “BB” is short, somber ode to famed Italian film director Bernardo Bertolucci, with whom Sakamoto collaborated on two films — the themes from The Sheltering Sky and The Last Emperor both appear later in the album. Bertolucci died of cancer in 2018 at the age of 77, five years before Sakamoto’s passing. — RH

3. Andata

The opening track from Sakamoto’s 2017 album async is one of the most heart-wrenching tracks I’ve heard. It’s piano Sakamoto at his most deliberate, developing a simple, elegant melodic line until its logical harmonic conclusion. Even outside the context of his cancer diagnosis, its slow, methodical churn is absolutely crushing. — RH

4. Solitude

As lonesome as its title implies, this cut from the soundtrack to Jun Ichikawa’s film adaptation of Haruki Murakami’s short story “Tony Takitani” is a master class in tension and release, building an almost unbearable burden with plinking, shadowy stabs with the right hand and sustained, knife-twisting arpeggios in the left. — RH

5. For Jóhann

A piece written for the widely acclaimed Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson who died suddenly in 2018 at just 48. The existential stakes of Sakamoto’s mourning of his contemporary and friend are deepened by the context Sakamoto wrote it in: himself a dying man, Sakamoto was face-to-face with the void a tragic death can leave behind. Like the best elegies, it’s as guilt-ridden as it is grief-stricken. — JD

6. Aubade 2020

Sakamoto had perhaps the most creatively successful career composing for adverts in history. “Energy Flow,” a piece written in 1999 for a Sankyo Pharmaceuticals TV ad, became the first instrumental song to reach No. 1 on Japan’s Oricon chart. “Aubade 2020” may not have started a similar revolution, but the number, by turns jaunty and sedate, continues Sakamoto’s legacy of pouring his entire heart into works most would view as inherently disposable. — JD

7. Ichimei - small happiness

Takashi Miike’s 2011 film Ichimei (or Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai outside of Japan) saw two giants of Japanese culture unite. Sakamoto’s score for the film undergirds Miike’s tale of heroism, honor, and tragedy. — JD

8. Mizu no Naka no Bagatelle

A bit of levity amid the overwhelming heaviness of Opus, “Mizu no Naka no Bagatelle” comes from a 1983 Suntory Whiskey TV ad. Gentle shades of Vince Gueraldi infuse the track’s lilting refrain, leaving the listener to imagine a long skate across a frozen pond (with an expensive glass of brown liquor at the other end). — RH

9. Bibo no Aozora

One of the many fan favorites Sakamoto returned to and rearranged many times throughout his career, “Bibo no Aozora” (first released in 1995) was introduced to a more mainstream western crowd as the score to the dramatic ending of Alejandro González Iñárritu’s 2006 film Babel, but its emotional complexity tells its own cinematic story — one better experienced without narrative accompaniment. — RH

10. Aqua

Another ’90s fan favorite, “Aqua” is a highlight from Sakamoto’s 1998 piano solo and duet album BTTB (Back To The Basics). Here, his love of clean, simple melodic lines and open harmonic spaces is on full display, resulting in a joyful, universally accessible work. — RH

11. Tong Poo

The oldest track on Opus — and the only Yellow Magic Orchestra song on the album — is also perhaps the most transformed from its source material. What was originally a maximalist city-pop thrill ride takes on a theatrical grandeur when reduced to its core components. With a lead foot on the sustain pedal, Sakamoto slows and muddies a track whose chipper aplomb is generally resistant to rearrangement, replacing it with the quiet confidence of a life well lived. — RH

12. The Wuthering Heights

The ingenuity with which Sakamoto manages to insert his signature style into the films he scores without any obtrusion of ego is always fascinating. His theme for Peter Kosminski’s 1992 adaptation of Emily Brontë’s tale of 19th-century rich-people drama on the English countryside hits all the proper emotional beats but retains a Ryuichi-ness that’s intangible but impossible to miss. — RH

13. 20220302 - sarabande

12, Sakamoto’s final album released in his lifetime, is a haunting document of mortality and everything we’re forced to leave behind like unfinished sketches on a draft table blown slowly out of the window. Sakamoto could have chosen to build or embellish on it here, but instead opts for a faithful performance of the song. In doing so, he stays true to its spirit. — JD

14. The Sheltering Sky

The theme from the Bertolucci flip of Paul Bowles’s fantastically titled, deeply depressing 1949 North African travelog gives no obvious indication of the “blood and excrement” that flavors the novel’s early climax, but there’s certainly a sinister undercurrent slowly seeping from the song’s perforated bowel. Still, it’s quite a lovely track. — RH

15. 20180219 (w/ prepared piano)

In Opus (the film), we watch Sakamoto painstakingly readjust a series of clothespins affixed to the middle strings of his piano, flicking and pitching them to ensure the sound matches his precise specifications. The ensuing song, original to the film, is the only track on Opus not rendered in perfect tonal clarity. The pins give Sakamoto’s slow block chords a raspy quality of a death rattle — dark, to be sure, but far from desperate. — RH

16. The Last Emperor

The work that solidified Sakamoto as a giant of modern composition, the score for Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1987 film The Last Emperor won an Academy Award for Best Original Score (Sakamoto shared the prize with David Byrne and Cong Su). — JD

17. Trioon

Opus’s only window into Sakamoto’s truly experimental realm. From 2002’s Vrioon — one of his many collaborative albums he made with German composer Carsten Nikolai (aka Alva Noto) — “Trioon” is another track in which our hero rips chords and melodies from their original context and reintroduces them as sweeping and balletic. Here, however, we’re given a slight hint at the song’s ambient origins: a static hiss that loses prominence throughout the track but provides a white-noise pedal point that anchors these sounds among the ghosts of the past. — RH

18. Happy End

Here, Sakamoto scrapes off the highly danceable rhythms of “Happy End” — a track funky enough for a YMO live rendition — transforming the tune into the walking song for the saddest college graduation you’ve never attended. — RH

19. Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence

Rightfully or not, the theme from Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence is Sakamoto’s most famous solo piece, and probably always will be. Its melodramatic flourishes make it far less subtle than his later work. Then again, Nagisa Ōshima’s tale of an English prisoner of war (David Bowie) and his sadistic guard (Sakamoto himself) does not call for subtlety (“HOMOEROTIC TENSION” is practically ticker taped to the screen in neon font throughout the film). In later interviews, Sakamoto said he struggled with the score and thought of consulting Bowie for inspiration but felt it would be inappropriate to distract him from his acting process. As incredible as a Sakamoto/Bowie collab sounds, it’s hard to imagine a more perfect soundtrack to this absolutely quirked-up Christmas classic. — RH

20. Opus - ending

Opus’s titular closer is the opening track from BTTB. Initially composing it for his opera LIFE, Sakamoto drew inspiration for the piece from Bach’s “Matthew Passion,” Satie’s Gymnopédies, and a long wait in traffic, it’s the ur-last waltz, the perfect ending to a proudly imperfect record. Opus is far from an exhaustive compilation of Sakamoto’s greatest hits — most of my favorite Sakamoto joints are omitted, in fact — but the rare insight it gives us into the mind of a true master as he stares unblinkingly into the abyss is far more valuable than that. — RH